On June 1, 2023, I was in Mexico City at the Universidad Iberoamericana to deliver the opening keynote at the 4th Global Business Anthropology Summit (GBAS). Looking out over the audience of applied and academic anthropologists in the Auditorio San Ignacio de Loyola, I was anxious to present my perspective that our field stands on the precipice of a disruptive “digital turn” driven by advancements such as artificial intelligence. While receptive audiences are never guaranteed, especially when proposing disciplinary transformation, I soon realized this crowd accepted my call for renewed professionalization.

During my talk, I observed attendees listening intently, many nodding in agreement as I described the need to embrace digital technologies as part of our practice to keep pace in an increasingly technology-mediated world. The lively Q&A session that followed signaled that these anthropologists, most of whom don’t work in tech, understood the urgency of developing new digital theories, methods, and communication abilities to stay relevant with adjacent disciplines.

However, the most significant validation came after I finished. As anthropologists from the audience approached me to continue the discussion, I was struck by their eagerness to push our discipline forward during this time of unprecedented change. From academic department chairs to organizational anthropologists to UX researchers, I witnessed a collective realization that embracing a digital turn in anthropology is imperative if we hope to remain relevant and impactful.

On Digital in Anthropology

In the 1965 book The Use of Computers by Dell Hymes, Claude Levi-Strauss argued that “the fundamental requirement of anthropology… is that it begin with a personal relation and end with a personal experience, but… in between there is room for plenty of computers” (Hymes 1965, 5). More than 30 years later, Alexander Chablo made a similar argument about artificial intelligence (AI) in Current Anthropology. In his article titled “What Can Artificial Intelligence Do for Anthropology?” he argued:

“I see artificial intelligence as offering several benefits to anthropology: knowledge elicitation techniques, ease in the analysis of field notes using knowledge engineer’s assistants, steady improvement in the sophistication of knowledge representation techniques and computer tools to assist in more detailed intracultural and cross-cultural comparisons, and new logics to help anthropologists understand human reasoning” (Chablo 1996, 555).

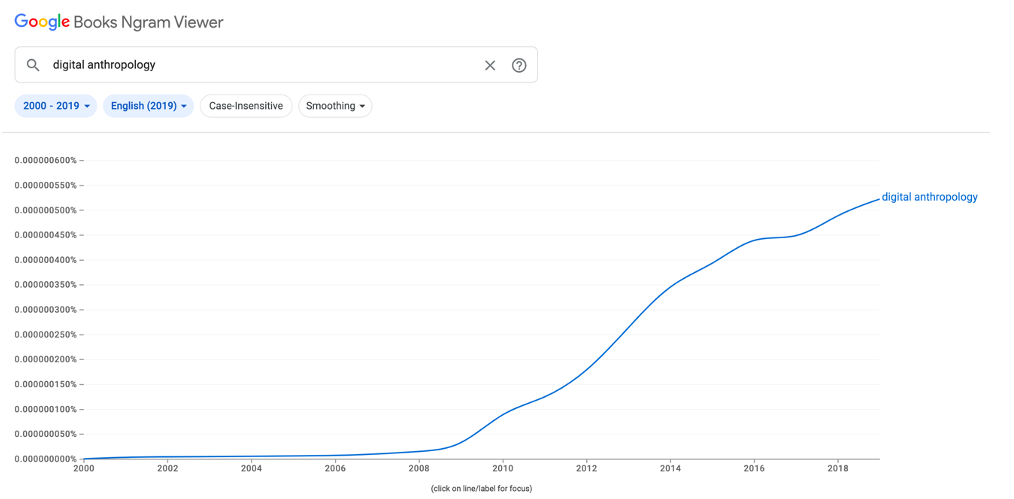

Since that time, the still-emerging field of digital anthropology has exploded. Starting in the early 2000s, it picked up speed around 2008, which is clearly visible by using Google Ngram Viewer, an online search engine that charts the frequencies of adjacent words (ngrams) in books between 1500-2019.

Figure 1. Google Ngram Viewer: Digital Anthropology Results for 2000-2019

The rise of digital anthropology was a direct response to the increased adoption of the World Wide Web, short message service (SMS), social media, and smartphones. Led by innovators such as Daniel Miller, Heather Horst, Tom Boellstorff, and Sarah Pink, what set this wave of digital-minded anthropologists apart was their focus on the digital as both a method and, importantly, a field site worthy of anthropological study. Notably, Daniel Miller, in a 2018 article for The Open Encyclopedia of Anthropology, defined digital anthropology as a term “used to refer to the consequences of the rise of digital technologies for particular populations, the use of these technologies within anthropological methodology, or the study of specific digital technologies” (Miller 2018).

However, since this first wave of innovators, a new group of early adopters have embraced a more modern take on digital within anthropology. Leveraging big data and making use of data science, graph theory, and artificial intelligence, this second wave of digital anthropologists are exploring new methodologies and analytical techniques to scale their abilities and complement the ethnographic practice by automating the collection and analysis of more data, of more modalities, be it physical or digital.

This trend, especially within the context of AI advancements, most notably the November 2022 release of OpenAI’s ChatGPT (GPT v3.5), has led to broad interest in digital technologies within the anthropology community, leading to my recent Journal of Business Anthropology article, “The Digital Turn in Business Anthropology” (Artz 2023).

While that article and my previous GBAS talk were framed around business anthropology, I argue the emerging digital turn applies to the broader anthropology community, and likewise, we must all begin to prepare for it, the AES community included.

Signs of the Digital Turn

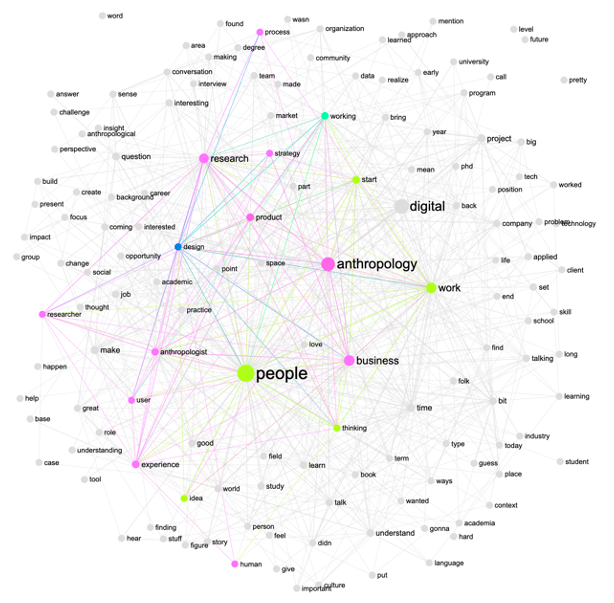

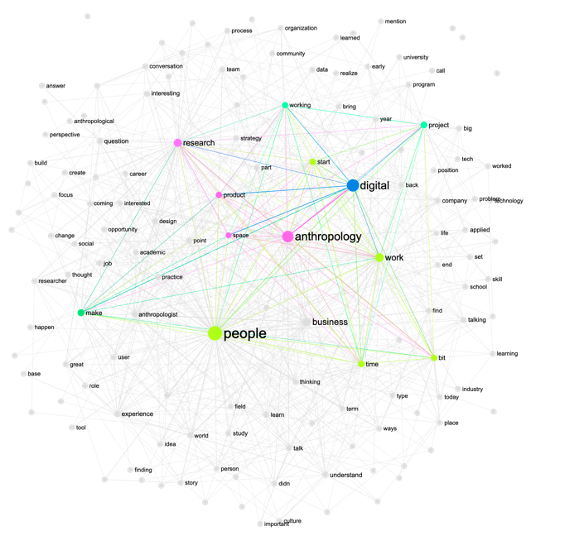

Despite the seeds of the digital turn being planted years ago, the recent digital boom within anthropology became apparent when recording my podcasts, Anthropology in Business and Anthro to UX. Since I started in 2021, digital technologies have become increasingly discussed, not just as a focus of our research and as products we build, but more so as advanced computational tools radically disrupting our work practice. The importance of digital applications within the overall body of work can even be seen when analyzing the transcripts of the podcasts. In both cases, ‘digital’ is a relatively significant node when conducting a semantic text analysis.

Figure 2. Semantic Text Analysis of Anthropology in Business

Figure 3. Semantic Text Analysis of Anthro to UX

Additional evidence can be seen in the growth of academic programs focused on computational and digital anthropology, such as the Techno-Anthropology MSc program at Aalborg University and the Digital Anthropology MSc program at University College London (UCL). The trend can also be seen in special journal issues, such as Big Data & Society’s Machine Anthropology, the American Anthropological Association’s Digital issue of Anthropology News, and the recent UNESCO and LiiV Center digital toolkit.

Moreover, and perhaps most compelling, some of the largest and historically conservative anthropological associations have started to emphasize the digital turn in conference and event programming. For example, the American Anthropological Association (AAA) put out a late-breaking call for AI topics to be part of the 2023 annual meeting, and it recently hosted the webinar, The Job of the Future: Digital Anthropology Meets Data Science. Similarly, the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland (RAI) held a 2022 virtual conference titled Anthropology, AI and the Future of Human Society. Even the Society for Economic Anthropology 2024 annual meeting call is focused on the data economy.

So, what does this all mean for our discipline?

Opportunities and Risks

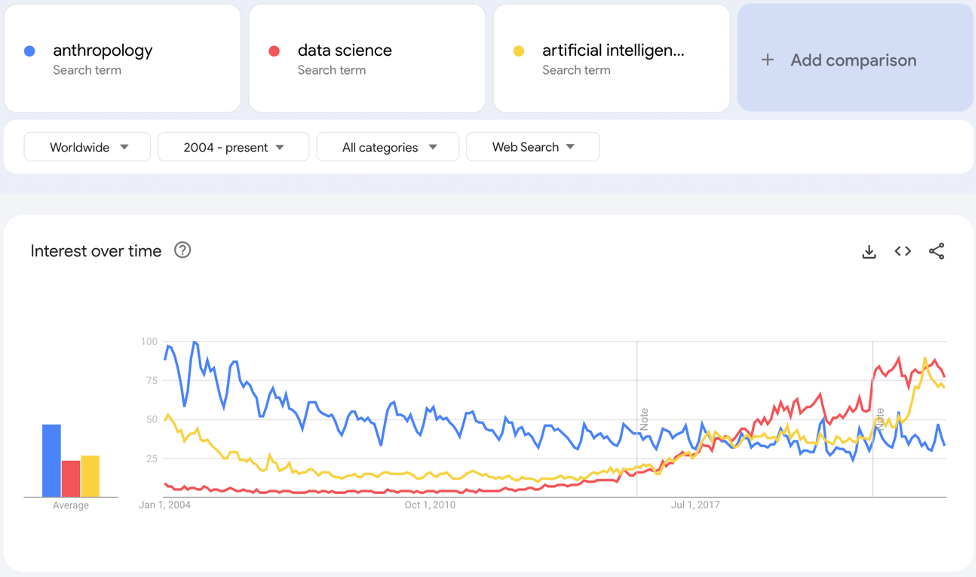

The truth is that the digital turn presents opportunities and risks that we will need to navigate to ensure anthropology retains its humanistic core while adapting its methods and perspectives to remain relevant in an increasingly technology-mediated world. But the potential risks are not a reason to stay stagnant and fall behind adjacent disciplines as sources of trusted knowledge. A statement that becomes painfully apparent when we compare how anthropology is trending against increasingly popular disciplines such as data science and artificial intelligence. Using Google Trends, we see that search interest has steadily declined for anthropology while these other disciplines gain in popularity, and though search interest alone may be a somewhat imprecise measure to benchmark disciplinary relevancy, we can at least take it as a signal of the popular imagination.

Figure 4. Comparing Search Interest for the Terms Anthropology, Data Science, and Artificial Intelligence

The Opportunities

Far from only being a risk, digital technologies offer anthropologists a tremendous opportunity to innovate and expand our impact, not just from a methodological perspective but also in the field sites we engage with. Recent work showcases this, with scholars embracing the digital turn to map controversies (Venturini and Munk 2021), explore our relationships with algorithms (Cury and Arora, 2023), and design recommender systems (Artz and Speicher 2023). But these just scratch the surface of what is possible when we embrace digital.

As I highlighted in my Anthropology News article, “Ten Predictions for AI and the Future of Anthropology,” there are immense possibilities on the horizon for all anthropologists, from AI-assisted multimodal ethnography to anthropology-specific AI tools that can analyze and interpret data with anthropological principles in mind. These opportunities will position AI as a collaborative partner capable of assisting us in both physical and digital field sites (Artz 2023). Potentially more significant, digital technologies can assist us in enhancing public engagement to capture the attention of more diverse groups and make it more likely that the general public will consume the information. From AI-enabled podcasts and vlogs to immersive storytelling, many exciting opportunities await us.

The Risks

However, fully embracing this future demands thoughtful and ethical engagement with these technologies. For as I have discussed previously, most notably in my 2022 Practicing Anthropology article on algorithmic bias, issues such as privacy, consent, algorithmic bias, job displacement, and climate impacts are very clear and present dangers (Artz 2022). These risks are not abstract concepts in some yet-to-be future but instead are already impacting how we discover media, who goes to jail or gets bail, who gets into college, who gets a loan, and even which scientific papers get seen and cited.

Additionally, the inclusion of digital methods, especially AI-based tools, which are typically a black box from the design perspective, represents direct threats to our practice, be it because of ethical issues related to data and privacy or incorrect results caused by biased data and models. Further, the heightened reliance on AI and automated decision-making may challenge our autonomy and a sense of purpose, ultimately disrupting our concept of belonging within the anthropology discipline.

For these reasons, we must remain vigilant and critical. However, we also can not only be armchair critics. Whether we like it or not, the digital turn is happening within society broadly and within anthropology specifically, and likewise, future professionalization efforts are needed to train anthropologists to work in digital field sites and with digital methods.

Getting Started

By this point, I am hoping you are asking yourself: how do I get started? While there is no one definitive community of praxis for incorporating digital into the practice of anthropology, a few suggestions would be to:

- Review all of the resources and papers that are either linked or cited in this article.

- Request more conference and event programming from all of the anthropology associations.

- Follow the work of Anders Kristian Munk and the Technology Anthropology Lab.

- Join the LiiV Center Digital Anthropology Slack in partnership with the Digital Anthropology Networking Group (DANG), which is an interest group within the AAA.

- Follow my personal (MattArtz.me) and business (Azimuth Labs) blogs, where I discuss all things digital and anthropology.

Digital Futures Await

The digital turn represents the next chapter in anthropology’s continuous evolution. As in eras past, new technologies bring both enticing possibilities and messy problems. But by embracing innovation thoughtfully, as we have done throughout our history as a discipline, anthropology can continue providing vital human-centered perspectives in our increasingly technology-mediated world.

References

Artz, Matt. 2022. “Design Anthropology, Algorithmic Bias, Behavioral Capital, and the Creator Economy.” Practicing Anthropology 44(2): 33–36. https://doi.org/10.17730/0888-4552.44.2.33

Artz, Matt. 2023. “Ten Predictions for AI and the Future of Anthropology.” Anthropology News, March/April 2023. https://www.anthropology-news.org/articles/ten-predictions-for-ai-and-the-future-of-anthropology/

Artz, Matt. 2023. “The Digital Turn in Business Anthropology.” Journal of Business Anthropology 12(1): 78-91 https://doi.org/10.22439/jba.v12i1.6919

Artz, Matthew R., and Geoffrey C. Speicher. 2023. “Gamified Participatory Recommender System.” US Patent Application US17/401,166, filed February 16, 2023.

Chablo, Alexander. 1996. “What Can Artificial Intelligence Do for Anthropology?” Current Anthropology 37(3): 553–55. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2744556

Cury, Maria, and Millie P. Arora. 2023. “Can People Have Healthy Relationships with Algorithms?” UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000384894?posInSet=3&queryId=261eb053-a737-4870-bae4-792c0ae6fde1

Hymes, Dell. 1965. The Use of Computers in Anthropology. Mouton. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783111718101

Miller, Daniel.2023 (2018). “Digital anthropology”. In The Open Encyclopedia of Anthropology, edited by Felix Stein. Facsimile of the first edition in The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Anthropology. Online: http://doi.org/10.29164/18digital

Venturini, Tommaso, and Anders Kristian Munk. 2021. Controversy Mapping: A Field Guide. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Polity Press.

Cite as: Artz, Matt. 2023. “Professionalizing Anthropology for the Digital Turn” American Ethnologist website, Nov 14, 2023. [https://americanethnologist.org/online-content/professionalization/professionalizing-anthropology-for-the-digital-turn/]

Matt Artz is an anthropologist specializing in user experience, product development and consumer insights. He is the founder of Azimuth Labs, an innovation consultancy leveraging anthropology, design, data science, and AI and an adjunct professor in the Gabelli School of Business at Fordham University. His work has been featured by Apple, South by Southwest (SXSW), and TEDx.