As an anthropologist working at the intersection of technology, business, and design, I often straddle two worlds with seemingly opposing philosophies. In industry, the mantra is “move fast and break things” to pursue disruptive innovation. Anthropology, on the other hand, champions careful observation, deep reflection, and nuanced critique. While both mindsets offer value, I argue that in an era of existential crises—from climate change to technosocial upheaval—anthropology has an ethical imperative to expand its scope beyond solely diagnosing problems towards actively proposing and enacting solutions.

From critique to solutions. Generated with GPT-4.

The Power of Anthropological Critique

This is not to dismiss the power of anthropological critique. Our discipline excels at revealing the complex, often hidden, cultural forces shaping human beliefs, behaviors, and systems. We illuminate the unintended consequences of well-meaning interventions and amplify the voices of marginalized groups. This critical perspective serves as a vital counterweight to the naïve techno-solutionism that assumes every societal ill can be neatly engineered away without grappling with entrenched power dynamics.

However, I fear that an over-emphasis on critique alone risks positioning anthropology as a field that tears down without building up. We’ve mastered pinpointing what’s broken in the world, but we rarely dare envision concrete alternatives or get our hands dirty fixing things, imperfect as those efforts may be. In remaining on the sidelines as evaluators hesitant to join the fray of intervention, we forfeit opportunities to shape real-world outcomes. Surely, there is a middle ground between unrealistic techno-optimism and paralyzing hyper-vigilance against unintended impacts.

The Urgency for Solutions-Oriented Anthropology

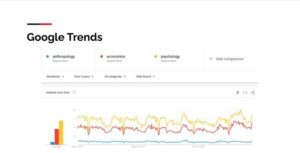

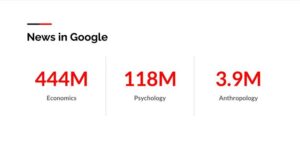

Embracing a more proactive, solutions-oriented stance becomes more urgent as traditional academic career paths for anthropologists erode. As Speakman et al. (2018) reveal, approximately 79% of US anthropology doctorates do not obtain tenure-track positions, with the number of graduates far outpacing available academic jobs. Simultaneously, the discipline commands diminishing public mindshare compared to fields like psychology and economics, as evidenced by stark disparities in search engine results and media coverage.

Comparing Google Search trends for anthropology, economics, and psychology. Screenshot taken from 2022 Why the World Needs Anthropologists presentation.

Comparing Google News results for anthropology, economics, and psychology. Screenshot taken from 2022 Why the World Needs Anthropologists presentation.

To remain relevant and expand employment prospects, anthropology must demonstrate its value beyond academia by tackling real-world challenges head-on. This requires evolving our identity, skillset, and engagement model. We need more anthropologists collaborating on interdisciplinary teams, translating insights into actionable recommendations, and rolling up their sleeves to co-create ethical sociotechnical innovations.

Anthropologists as Innovators in EmTech

In my recent co-edited volume, EmTech Anthropology: Careers at the Frontier (2024), Lora Koycheva and I showcase compelling examples of anthropologists embracing solution-oriented approaches in the emerging technology (EmTech) sector. For instance, Laura Musgrave demonstrates how her work ensures more responsible AI development by guiding conversational AI technology and policy to mitigate bias and increase transparency.

Similarly, I shared my journey as a co-founder of an art tech startup, designing a gamified participatory recommender system that promotes equity for creators. By combining ethnographic research with computational methods, I reimagined traditional approaches to machine learning recommender systems to counteract biases that disadvantage artists lacking access to economic, social, and cultural capital.

Similarly, Melyn McKay exemplifies how anthropological theory can inform the trajectory of blockchain-based products to serve excluded communities better. Drawing on theories of value, exchange, and extra-state relations, she details how she is leading the development of equitable Web3 alternatives in the payments sector.

These stories embody the potential for anthropologists to move beyond critique and actively shape the direction of our society for good. By integrating ethnographic insights with participatory design and interdisciplinary collaboration, our authors demonstrate how anthropology can prioritize equity, inclusion, and human dignity while working towards solutions.

Reclaiming Solutions Through an Anthropological Lens

As we elaborate on in EmTech Anthropology, now is the time for anthropology to pivot from a discipline primarily defined by insightful critiques to one equally known for enactment and solutioning. Doing so will require renegotiating our relationship to “solutions”—interrogating the term’s baggage while reclaiming it to include participatory, iterative, and reflexive problem-solving. It means updating graduate training to equip students with interventional design skills alongside theory and methods. And it demands normalizing alt-ac career paths where anthropologists work in change-maker roles across industry, government, and nonprofits.

To be clear, this is not a call to abandon anthropology’s soul of critical perspective, attention to context, or focus on equity. Rather, it’s a provocation to build upon that foundation by empowering anthropologists as active agents in envisioning and enacting more just and flourishing futures. In an era of unprecedented global challenges, anthropology cannot afford to remain a detached observer but must actively engage in shaping solutions.

With so much at stake—ecologically, economically, socially, and technologically—we must channel our hard-won insights more directly toward positive change. This contemporary moment demands nothing less than solutions-oriented anthropologists leveraging our holistic understanding of the human condition to address today’s most pressing challenges while shaping a more equitable tomorrow.

References

Artz, Matthew R., and Lora Koycheva. 2024. EmTech Anthropology: Careers at the Frontier. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003458555

Artz, Matt. 2022. “Why the World Needs Creator Anthropologists.” Paper presented at the Why the World Needs Anthropologists (WWNA) Conference, Berlin, Germany. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z5ypNTgKL0M

Artz, Matthew R., and Geoffrey C. Speicher. 2023. “Gamified Participatory Recommender System.” US Patent Application US17/401,166, filed February 16, 2023. https://patents.google.com/patent/US20230046646A1

Speakman, Robert J., Carla S. Hadden, Matthew H. Colvin, Justin Cramb, K.C. Jones, et al. 2018. “Market Share and Recent Hiring Trends in Anthropology Faculty Positions.” PLOS ONE 13(9): e0202528. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0202528

Matt Artz is an anthropologist, designer, and technologist specializing in AI product development. He is the founder of Azimuth Labs, host of the Anthropology in Business and Anthro to UX podcasts, and co-editor of EmTech Anthropology and the forthcoming Anthropology and AI. His work has been featured on TED, UNESCO, South by Southwest, and Apple’s Planet of the Apps.