“Whoever is united to us by any connexion is always sure of a share of our love proportion’d to the connexion, without enquiring into his other qualities.” – David Hume

After washing my hands, I took a clean t-shirt and jeans out of my backpack, unzipping the outer pocket to fish out the garbage bag I had brought with me. After changing in the visitor bathroom, I stuffed my jacket and the rest of the clothes I had worn during the drive from my house to the hospital into the garbage bag, shoving the whole package into my backpack. I washed my hands again, pushed the bathroom door open with my elbow, and started walking down the hallway.

On the oncology floor, the nursing station is halfway between the visitor bathroom and my dad’s room at the end of the hall. I stopped to ask one of the nurses about their new garbage bag policy. She looked confused. “We don’t have a garbage bag policy,” she said. After awkwardly excusing myself, I went to see my dad. He was asleep, flushed with fever. I sat on the recliner next to his bed.

Earlier that day, when we had talked on the phone, my dad told me the latest news from the night nurse: To reduce the spread of potentially dangerous microorganisms, no clothes from the outside world can be worn on the ward. Visitors should bring a clean change of clothes and store used outerwear in a plastic garbage bag. An intensive drug regimen and months-long confinement had left my dad with an increasingly tenuous ability to distinguish between reality and dream. I knew that, but the new policy had seemed believable. We had already changed our hygienic practices in myriad ways, doing anything we could to avoid testing my dad’s practically nonexistent immune system. Why not a garbage bag policy, too?

I watched him sleep. This is my dad: enthusiastic dance recital attendee, basketball coach, inventor of ridiculously silly and creative birthday parties, and regular organizer of family fire drills to prepare me and my sister for any emergency. He and I both daydream when we should be paying attention and have the same habit of absentmindedly rotating one foot. If packing away potentially germ-ridden clothes from the outside world made my dad feel safer—more protected from the invisible microbes that loom especially large for the immunocompromised—then of course that is what I would do.

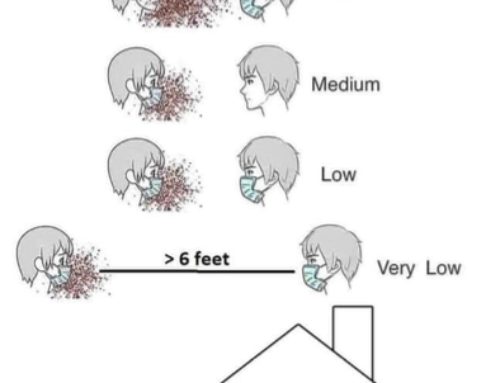

That was in 2015. Today’s reality—life with Covid-19—has grown uncomfortably similar to the stuff of my dad’s once feverish nightmares. As people around the world adjust to this new way of being, I am struck by the resemblance between the protective behaviors asked of the public and those expected of cancer patients and other immunocompromised people. In the pre-Covid-19 world, the onus was on the immunocompromised individual to protect herself from the germ-ridden behaviors of everyday life by social distancing. Today, social distancing is the germ-avoiding behavior of everyday life.

The process of coming to terms with the new ethics and sociality of everyday life with Covid-19 has been uneven. In the United States, media reports of young and healthy people’s lack of concern have circulated widely. The weekend after many universities made the decision to close doors, crowds across the country flooded bars to celebrate St. Patrick’s Day. Spring breakers flocked to beaches with a sense of laissez faire (in)famously articulated by the young man who declared in a televised interview, “If I get corona, I get corona” (Ortize 2020). (He later apologized.)

Reading these cases as a lack of appreciation (if not a total disregard) for the heightened interdependence of pandemic times, I found myself puzzling over a question that I am sure most public health officials share: How do you move people to care about strangers?

I am far from the first person to ask this question. The eighteenth-century empiricist philosopher David Hume was preoccupied by it, viewing the cultivation of care for one’s fellow citizens as a central challenge for government. Hume believed that the key to moving people to care was sympathy. Observing that a person’s sympathies (along with feelings like love and care) are typically strongest in their immediate circle, where a person’s social ties are most intimate, and weaken as relations grow more distant, Hume thought that resemblance played an important role in eliciting sympathy and thus in producing love and care: It is easier for us to believe we think and feel like another when we understand their experiences to resemble our own. Though people have the capacity to feel sympathy for strangers, as Danilyn Rutherford argues, drawing on Hume, the “vividness of their sympathies dissipates over space and time” as the perceived resemblance grows dimmer (Rutherford 2009). The puzzle is how to move people to extend their sympathies beyond this close-knit circle of resemblance.

Recently, I have been watching this play out on Twitter, which has amassed a growing assemblage of tweets posted by people who describe themselves or their loved ones as “high risk” for Covid-19. What many of these tweets have in common is an intention to move strangers to care through the cultivation of resemblance. Reading them, I have been struck by the power of these tweets, shared by strangers, to evoke feelings of familiarity, even intimacy, among those who respond and interact with them. I, too, have felt moved. What accounts for the affective weight of these messages? What can they teach us about the politics of sympathy?

While it is difficult to mark a single origin to any social media event, a handful of tweets on March 14, 2020 posted by a small group patient advocates, including Molly Schreiber, a patient advocate living with both type 1 diabetes and rheumatoid arthritis, met with a landslide of responses. Schreiber posted a smiling selfie and the following text: “I am immunocompromised and my life counts. #HighRiskCovid19 Please join us in putting a face to those who are vulnerable to the #coronavirus.”

By the next day, nearly 85,000 tweets had been posted using the hashtag #HighRiskCovid19, with thousands of personal stories and images shared (Gelman 2020). In a public conversation characterized by graphical abstractions, these personal appeals made the seemingly distant and abstract feel immediate and vivid (see Storz and Wynfield, this collection). An arthritis patient advocate, Jennifer Walker, made this approach to #HighRiskCovid19 explicit, “If folks are exposed to real life people instead of just numbers or an idea then it makes the reality more tangible. It brings the risk into real life instead of abstract. [People] get to see our humanity and how we shouldn’t be dismissed” (Gelman 2020).

Imagining the real person behind an abstraction might lead people to particular ethical understandings. Anthropologist Alison Cool’s research with biobank researchers in Sweden suggests that even data experts—people trained to care for abstract populations—formulate their ethical commitments through the stories they tell themselves about the “real” people behind the data. The stories they tell often conjure a person with values that resemble their own (Cool 2019). The #HighRiskCovid19 tweets appear in this spectrum between abstraction and imagination, inserting the story of a real person who wants the viewer to see their life as equally worth living and protecting. Though there was great variety in how contributors chose to represent the “real” story of their lives, two approaches stood out to me in thinking with Hume’s concept of sympathy.

The first approach involved the cultivation of resemblance with an imagined healthy (and seemingly white American middle-class) other, as seen in the two examples above. This category of tweets featured images of healthy and happy-looking people whose Covid-19 risk status might surprise onlookers. Many of these tweets also featured more than one person, rooting the high-risk individual in a web of social relationships that made them legible as someone who could be your sister or daughter or father—with all the past experiences those relationships call to mind. Aesthetically, these tweets reminded me of mainstream breast cancer advocacy campaigns in the United States, which “have stressed their ‘ordinariness’ and ‘moral worthiness’” (Epstein 2016).

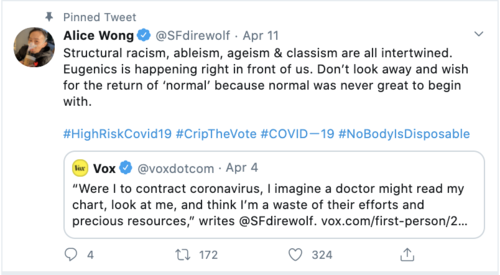

Rather than appealing to a shared “ordinariness,” this second category of tweets engaged in something closer to “a politics of radical empathy,” refusing to sanitize, visually or textually, their differences for an imagined viewer (Checker, et al. 2014). These tweets challenged the idea of assessing worthiness based on one’s ability to appeal to normative ordinariness. As news stories about heath care rationing and hospital triaging policies circulated in late March and early April, new hashtags began to emerge alongside #HighRiskCovid19 including #NoBodyIsDisposable—recently revived by Fat Rose, a fat liberation group who had initially used the hashtag to protest ICE detention centers—and #NoICUGenics (Cortese 2020). These hashtags became a website, organized by the “people targeted by triage plans during the Covid-19 pandemic—people with disabilities, fat people, old people, people with HIV/AIDS or other illnesses—and our loved ones who don’t want us to die,” with instructions for posting “solidarity selfies” (nobodyisdisposable.org).

Though they share the same goals, these two approaches offer different answers to my initial puzzle: How do you move strangers to care? While an in-depth analysis of their respective impacts is outside the scope of this essay, I suggest there are several insights to be gleaned about the politics of sympathy.

First, sympathy can be a powerful affective tool for moving strangers to care. In my research with people with type 1 diabetes, my interlocutors have described how learning that a stranger shares their diagnosis gives them a vivid picture of what kind of person they understand the stranger to be. Believing their life experiences to resemble one another is enough to bring that stranger into their personal circle of trust and care. In following #HighRiskCovid19, I have found myself similarly moved by images of fathers and daughters or by the heartfelt words of caregivers whose loved ones have cancer. My belief in our shared experiences brings a vividness to my sympathies, evoking a sense of moral obligations akin to those I feel toward my dad. But sympathy, as an affective tool, is narrow in scope: Why do some faces stop us in our Twitter-scrolling tracks while others remain strangers, easy to scroll past? The production of sympathetic feelings—and their more egalitarian cousin, empathy—never happens in a political vacuum: They emerge in the context of our circle and who we imagine belongs in it.

Second, sympathy is never a neutral project nor is care an apolitical good—and sympathy grounded in perceived similarity may come at the cost of a more expansive form of social solidarity. On the one hand, it assumes that we do not already care for those unlike ourselves. On the other, it suggests that those who are not cared for should take responsibility in order to earn our sympathy—if only they could perform relatability more legibly, then we might be moved to care. Further, even when sympathy is achieved, even when we recognize ourselves in them, there is no guarantee that it will elicit a positive response. As Rutherford observes, sympathy “can spawn hostility as easily as love” (Rutherford 2009). Self-hatred can be extended as generously as self-love. This is all to say, sympathy may not be the affect our politics demand.

I do think, however, that a change in politics could affect our sympathies, broadening our circles of care—expanding who moves us to answer “of course.” In the history of patient advocacy movements, many disease-based efforts have been narrowly focused, taking a zero-sum approach. But there are also examples of movements that have mobilized across difference—across disease, race, class, gender, and sexuality—to promote a more inclusive and intersectional healthcare agenda (Epstein 2016). I am cautiously optimistic that the unfolding patient advocacy movements of this moment may prove to be the latter—a stand in solidarity rather than similarity, a radical care that responds to vulnerabilities without demanding resemblance.

Acknowledgements: I would like to thank my dad for trusting me to tell the stories he does not remember, and my mom for remembering with me.

References:

Banach, Je. 2020. “I Am High-Risk for Covid-19—We Need to Talk.” Vogue (online), April 1.

Checker, Melissa, Dána-Ain Davis, and Mark Schuller. 2014. “The Conflicts of Crisis: Critical Reflections on Feminist Ethnography and Anthropological Activism: Public Anthropology.” American Anthropologist 116(2): 408–9.

Cool, Alison. 2019. “Impossible, Unknowable, Accountable: Dramas and Dilemmas of Data Law.” Social Studies of Science 49(4): 503–30.

Cortese, Claudia. 2020. “Even during a Pandemic, Fatphobia Won’t Take a Day Off.” Bitch Media (online), April 2.

Epstein, Steven. 2016.“The Politics of Health Mobilization in the United States: The Promise and Pitfalls of ‘Disease Constituencies.’” Social Science & Medicine 165: 246–54.

Gelman, Lauren. 2020. “This #HighRiskCovid19 Hashtag Took Off on Twitter This Weekend and You Need to Know Why.” Creaky Joints (online), March 15.

Hume, David. N.d. “A Treatise of Human Nature.”

Ortize, Aimee. 2020. “Man Who Said, ‘If I Get Corona, I Get Corona,’ Apologizes.” The New York Times (online), March 2.

Rutherford, Danilyn. 2009. “Sympathy, State Building, and the Experience of Empire.” Cultural Anthropology 24(1): 1–32.

Cite as: Edmiston, Paige. 2020. “Cultivating Resemblance: Moving Strangers on the Internet to Care.” In “Pandemic Diaries: Affect and Crisis,” Carla Jones, ed., American Ethnologist website, May 20 2020, [https://americanethnologist.org/features/pandemic-diaries/pandemic-diaries-affect-and-crisis/cultivating-resemblance-moving-strangers-on-the-internet-to-care]

Paige Edmiston is a PhD student in anthropology at the University of Colorado. She studies how the open-source software movement is changing the U.S. medical system.