I hung up the phone around 9 pm on March 15, 2020, shaking with anger and frustration. My mother, residing in Yangon, Myanmar, sounded heedless to the global spread of Covid-19. She shrugged off my concerns about her planned vacation to northern Myanmar in a few weeks with her friends, all in their 60s. Instead, she proudly informed me that there were no cases in Myanmar, and that Buddhist monks had been chanting mētta thouq1 day and night to protect the population. My mother’s attitude was unsurprising. In her March 16, 2020 nationwide address, State Counsellor Aung San Su Kyi stated that there were no Covid-19 cases in Myanmar regardless of its shared border with China. Meanwhile, about 8,000 miles away in my current home in Colorado, panic in the face of increasing cases and deaths took the now familiar form of mass buying of toilet paper, cleaning supplies, and groceries. While my local government issued stay-at-home orders, the tea shops in downtown Yangon remained open. This stark contrast between public worry in the United States and apparent calm in Myanmar piqued my interest. What sentiments pervade a now infected Myanmar? Has public sensibility shifted as evidence of the virus has been confirmed in the country?

One key site for the expression and circulation of perceptions of viral risk in Myanmar public are satirical cartoons, memes, and parodies. Consider the public Facebook group: “Myanmar COVID-19 Community.” Since its creation on March 18, 2020, it has ballooned in size with 184 admins and moderators, as well as nearly 800,000 members and rising at the time of this writing. The primary language of the group is Burmese. Daily news about the pandemic dominates group posts, and users seem to live primarily in urban Yangon and Mandalay. Simultaneously a source of information and a site for mockery, users’ posts report news about outbreaks while questioning official statements intended to reassure the public. Mockery as humor is a familiar topic to anthropologists. Humor can be used as “a containment strategy enabling its users to invoke taboo topics without breaching the norms that define these topics as toxic” (Hall, Goldstein & Ingram 2016, 73). Public mistrust about state responses to the pandemic are especially accentuated in playful parodies of nationalist love. As a result, satirical cartoons and memes about the virus blend skepticism and suspicion to achieve a particular affective pleasure, popularly referred to as “gali-hto” or tickling. Tickling is a longstanding feature of Myanmar’s sociopolitical life, generating laughter and critique while avoiding state retribution, (see Leehey 2005, 2010).

Humor can hold both love and skepticism. Cartoons shared before the first reported positive cases in the country concealed the public suspicion about the absence of the virus under the mask of apparently unwavering nationalistic love. The cartoon in Figure 1 (below), posted on March 20, 2020, appears with the title “ဗြိတိသျှတွေကို သနားတယ် /I feel pity for the British.” In it, the UK speaks, calling British citizens to return home because Myanmar has poor medical facilities. In response, the meme’s creator mocks the former colonizer for its increasing infections, gloomy weather, and “shortage of toilet paper,” while boasting that Myanmar has zero positive cases and a humid tropical climate. However, this list of advantages is not the sole punchline. Instead, Myanmar also has “supernatural medicine Sayar Kho,” a traditional rubbing ointment used for minor illnesses such as cold, fever, headache, muscle pain, and bruises. The pitiable UK has no such medicine.

Figure 1: I feel pity for the British

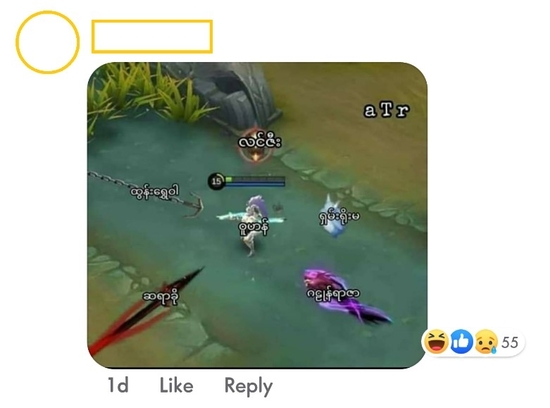

This joke is extended in another meme posted to the group, shown in Figure 2 below. Dubbed on to a screenshot of a popular multiplayer online battle game Dota, the enemy avatar “Wuhan” is attacked by fighting avatars “Tun Shwewar,” “Linzee,” “Shan Yoema,” “Galone Yarzar,” and “Sayar Kho,” the names of popular Burmese brands of traditional rubbing ointments. Teaming up, the ointment avatars heroically vanquish the foreign threat.

Figure 2: Rubbing oil tournament

These images profess affection for the Burmese nation even as they mock the Myanmar state’s response to the virus. Delight in critiquing a former colonial power, or a contemporary powerful geopolitical neighbor, suggest that Myanmar is not a comparatively smaller and poorer country. Consider the idea of “pity” for British subjects. The Burmese concept of pity or thana here operates similarly to Catherine Lutz’s theorization of the Ifaluk value of fago (love/compassion/sadness) in Micronesia (1988). Like fago, showing thana is an expression of care for the needy that emphasizes the caregiver’s powerful rank and maturity. Expressing pity for British citizens tickles because it seems to invert a traumatic memory of subjugation.

Yet equally ticklish is a sense of vulnerability, a subtle yet ludic acknowledgement that ointments might not be sufficient treatment for a highly contagious and deadly virus and that the low rates of infection may simply be a function of the fact that testing has been unavailable. A cartoon by Swe Thar and Salai KKP mocks nationalist enthusiasm (see Figure 3 below). The instantly recognizable character of a precolonial Burmese ambassador, dressed in red Burmese royal court attire, reads aloud the news of the pandemic: “There are no positive cases of coronavirus in Myanmar!” The public, represented by a man in the cartoon, bellows with joy: “Such great news!” In the second sequence, the ambassador continues: “We don’t have a machine to test the virus either.” This time, his announcement is followed by the man disappearing into the air exclaiming: “သေပြီဆရာ” (roughly equivalent to the English exclamation, Oh my gosh!).

Figure 3: “There is no machine to test Coronavirus in Myanmar either!”

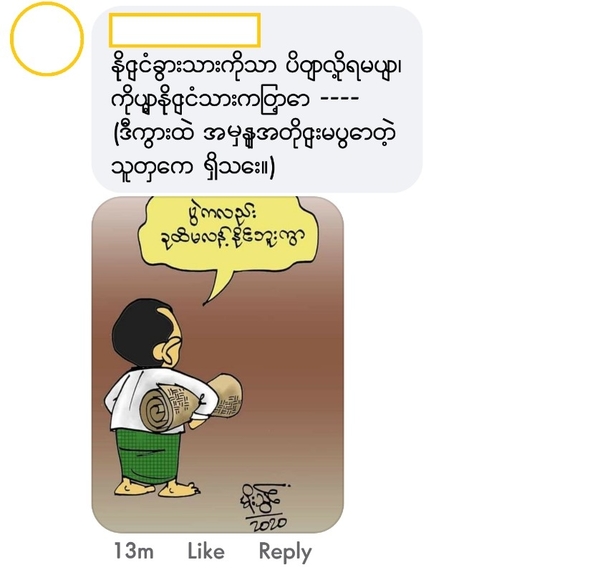

Distrust is a recurring theme. In a cartoon by Moe Thwin (Figure 4), a commenter shows a similar sense of distrust. This cartoon depicts a man holding a rolled-up bamboo mat. The man says: “I can’t wait for the show to go wild.” This cartoon intertextually refers to a Burmese proverb: ပွဲလန့်တုန်း ဖျာခင်း or “one must unfurl the bamboo mat while the show goes wild.” The proverb refers to the practice of all-night theater in Myanmar in which attendees are responsible for bringing their own bamboo mats to claim a good spot. The appropriate strategy is to arrive early to claim a good spot. Opportunistic spectators may wait for a disruption to snatch a good spot when the show and the crowd begins to get out of control. The proverb connotes the self-centered behavior that can arise in a crisis. A comment accompanying the cartoon notes, “We can only restrict the foreigners, but what about our own citizens? Amid all this, there are still liars.” Thus, while the state was limiting and tracing foreign arrivals as potential carriers of the virus, individuals worried about the state’s inability to trace the virus spreading among citizens, and its inability to manage greedy behavior by citizens. In the following days, group posts proliferated with images shaming people for selling masks at inflated prices.

Figure 4: Waiting to unfurl the bamboo mat

These cartoons join a longstanding Burmese satirical tradition of mocking state and elite authority. Anthropologist Elliott Prasse-Freeman theorizes this rhetorical genre as “catachrestic interpellation” (forthcoming). He argues that cartoons (mis)interpellate the overhearers—the embedded characters and/or the real-world Burmese elites—by indirectly engaging in saungpyaw, the act of eliciting the morally correct affective response to corruption: guilt. Any Burmese reader familiar with saungpyaw, or “the unfurling of bamboo mats” in Myanmar’s sociopolitical life, would find an otherwise upsetting image amusing.

Unfortunately, public suspicion about nationalist pride was confirmed in the days after their appearance. On March 23, 2020, Myanmar reported two positive cases of Covid-19. Within a week, the number had risen to eight. Pre-coronavirus humor began to take on a more vigorous and intense critique of the state response. On March 26, 2020, a group member shared a YouTube video in the Myanmar Covid-19 Community. The video was published on March 25, 2020 by the account AZ39. The thirty-five-second video depicts a group of astronauts, named “Myanmar,” “Chaina” (sic), “Italy,” and “America” being attacked by a monster named “coronavirus” (see Figure 5). The monster attacks and kills each astronaut, starting with the USA, then Italy, followed by China. The monster, however, misses the terrified astronaut representing Myanmar who hides behind a rock. As the monster makes its way back to the hole with no astronaut in sight, the Myanmar astronaut farts loudly which prompts the monster to notice Myanmar’s presence. The video ends there. Unlike the cartoon in Figure 1, the video openly treats with humor the fear of facing coronavirus in a country that is unprepared.

Figure 5: Myanmar farts

This essay cannot fully capture Myanmar’s complex political and emotional landscapes in a pandemic, but it suggests that ticklish humor is one form of therapy for vulnerable subjects in an intense crisis. Layered laughs provide pleasure because they require a semiotic fluency that is equal parts shared affection for Burmese sensibilities and disappointment in Burmese leaders. They keep hope afloat in a national context where fear has a long history of being used for containing and managing political dissent (see Skidmore 2004). Implicitly and explicitly, they try to shame the state for its failure to care for its citizens, prepare for risk, and limit extortion by elites. Visual anthropologist Karen Strassler argues that cynical humor in post-New Order Indonesia is not merely “a return to the cynicism of the authoritarian past,” but an expression of ongoing public desire for political transparency (2020, 129). In quasi-authoritarian Myanmar, cynical humor is an ambivalent site through which the public exploits taboo topics like “politics” (nain ngan ye) by demanding accountability from the state (Walton 2015, 509).

My mother’s hasty pride has now dwindled, and her vacation has been canceled. The Myanmar COVID-19 Community remains a hub for sharing information, asking questions and for help, and above all, to jeer at and show signs of doubtful love for the state’s pandemic-related news and actions. Laughter has always been “the weapon of the weak” (Goldstein 2003), but it might also become a weapon of the powerful.2 When the pandemic is over, we might as well be laughing together, tickled to tears by these humorous satires once deemed inappropriate.

Notes:

[1] A Theravada Buddhist sutta usually chanted by the Buddhist clergy and laypeople and believed to protect all sentient beings from danger and anxiety and to spread peace and tranquility. In Myanmar, mētta thouq has historically been associated with politico-religious participation. For instance, in the so-called Saffron Revolution in 2007, the Buddhist monks chanted metta thouq to not only spread peace but also to evoke shame and guilt from the state officials who increased the sale prices of fuel (see Walton, 2015 for more details on the political participation of monks in Myanmar)

[2] Hall, Goldstein, and Ingram (2016) have precisely argued for this point in their analysis on the entertainment value of Donald Trump.

References:

Goldstein, Donna. 2003. Laughter out of Place: Race, Class, Violence, and Sexuality in a Rio Shantytown. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Hall, Kira, Donna Goldstein, & Matthew Brue Ingram. 2016. “The Hands of Donald Trump: Entertainment, Gesture, Spectacle.” HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 6(2): 71-100.

Leehey, Jennifer. 2005. “Writing in a Crazy Way: Literary Life in Contemporary Urban Burma.” In Burma at the Turn of the 21st Century. Skidmore, Monique (ed). Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

Leehey, Jennifer. 2010. Open Secrets, Hidden Meanings: Censorship, Esoteric Power, and Contested Authority in Urban Burma in the 1990s. Doctoral Dissertation. University of Washington.

Lutz, Catherine. 1988. Unnatural Emotions: Everyday Sentiments on a Micronesian Atoll and Their Challenge to Western Theory. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Prasse-Freeman, Elliott. Forthcoming. Rights and Refusal: Cursing Burma’s Transition.

Skidmore, Monique. 2004. Karaoke Fascism: Burma and the Politics of Fear. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

Strassler, Karen. 2020. Demanding Images: Democracy, Mediation, and the Image-event in Indonesia. Durham: Duke University Press.

Walton, Matthew J. 2015. “Monks in Politics, Monks in the World: Buddhist Activism in Contemporary Myanmar.” Social Research: An International Quarterl. 82(2): 507-530.

Cite as: Paing, Chu May. 2020. “Viral Satire as Public Feeling in Myanmar.” In “Pandemic Diaries: Affect and Crisis,” Carla Jones, ed., American Ethnologist website, May 20 2020, [https://americanethnologist.org/panel/pages/features/pandemic-diaries/pandemic-diaries-affect-and-crisis/viral-satire-as-public-feeling-in-myanmar/edit]

Chu May Paing is a PhD student in cultural and linguistic anthropology at the University of Colorado at Boulder. She is planning on conducting research on urban visual culture in her hometown of Yangon, Myanmar. She can be reached at chu.paing@colorado.edu