The coronavirus hit fast. One day I was in class preparing to transition to remote learning and the next I was on a plane home to Cincinnati. As I slowly processed the fact that my summer plans were now off and that much of what I considered normal life might never fully return, I found solace at my oldest sister’s house eating with her family, watching TV, and playing with her three young children. I also quickly found myself spending much more time online. Predictably, social media proved both soothing and agitating until, one day, a particular tweet gave me some fleeting hope.

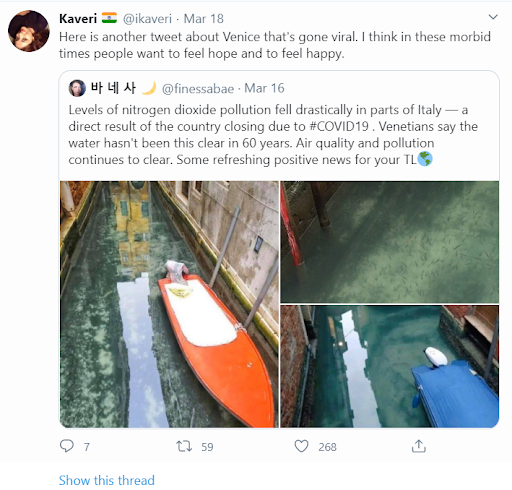

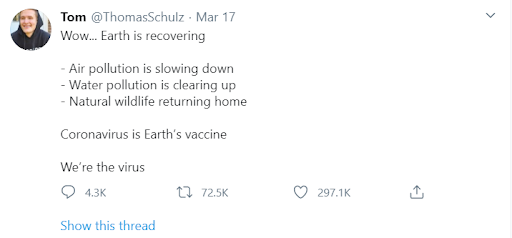

The tweet claimed to document pristine canals in Venice, Italy, that were newly clean due to the absence of human activity from the Covid-19 lockdown (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1

Figure 2

My initial reaction was, this is great news! I continued to scroll through the pictures, feeding my relief that at least something was going right in a world experiencing so much fear and grief. Hope is always a beautiful thing, but like many fellow travelers in the Twitter universe, I found this narrative exceptionally soothing. That is, until I encountered an additional tweet informing us that the images were inaccurate. They had been taken on an island off of the coast of Italy where the canals are typically clear and swans are present.

My heart sank. I felt as though I had been bamboozled. Why did I want it to have been true? Why did it feel so good to briefly dream that at least the environmental crisis could be diverted in the face of an epidemiological one? And what did the fact that so many others shared this hope reveal about the role of environmental solutions in treating our trauma? Tracking tensions about the positive environmental stories that have circulated in the past six weeks, I found that the desire for radical alternative environmental futures is a potent social feature of the pandemic. Images of bluer skies in Los Angeles, graphs of fewer pollution-related deaths in China, lions relaxing in South Africa, wild goats grazing on a main street in a Welsh city, all are now part of a genre of social media memes suggesting that for some creatures, 2020 has not been tragic. Undergirding these optimistic “image-events” (Strassler 2020) is the sense that the pandemic has produced an overdue correction in which non-humans are reclaiming their rightful place in the earth’s balance of activity (cf. Parreñas 2018). It suggests that human suffering from the defiant, global movement of a virus might force humans to acknowledge the intimate nature of interspecies relationships. In short, it harnessed the fear and pain of human mortality to the affective allure of a simple explanation of the cause, and perhaps the solution.

“Humans are the real virus”

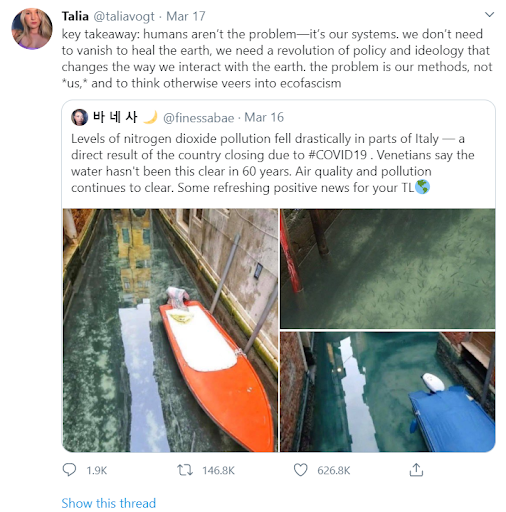

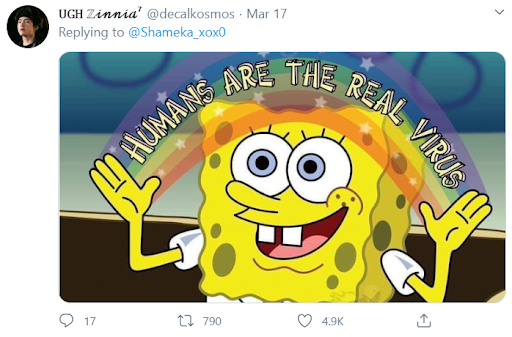

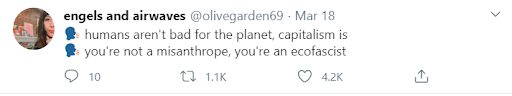

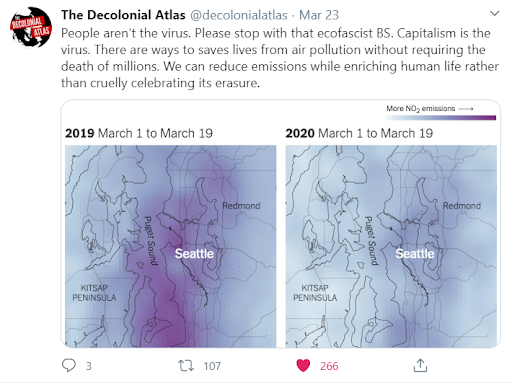

Many of these posts directly blamed human violence against the environment as the cause of the viral pandemic, playfully but angrily inverting the suggestion that humans must develop a vaccine to save themselves. Instead, as @ThomasSchulz posted, the virus was the way the planet was immunizing itself against humans, the true virus (Figure 3). Comments in his and similar posts quickly accused users of “ecofascism” for suggesting that individual humans, rather than extractive, profit-driven systems, were the cause. These comments suggested that continuing to facilitate the circulation of inaccurate images such as those of Venice reinforced facile ideas about human responsibility and distracted from the real cause of the crisis (Figure 4).

Figure 3

Figure 4

As I sorted through my disappointment that these images were not reliable and that I should not feel upbeat about a future that included interspecies harmony, I was perplexed by @taliavogt’s suggestion that circulating or savoring these images was tantamount to ecofascism. Ecofascism refers to “the promotion of authoritarian, fascist ideologies for environmental good… minimizing or even encouraging human death and suffering so long as it helps the environment” (Garcia 2020). My Twitter feed proliferated with similar sentiments, suggesting that humans are the virus infecting the earth (Figure 5). Clearly, I was not alone in the simple allure of the idea that “humans” were responsible.

Figure 5

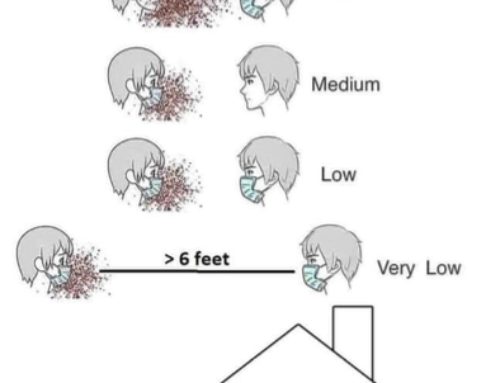

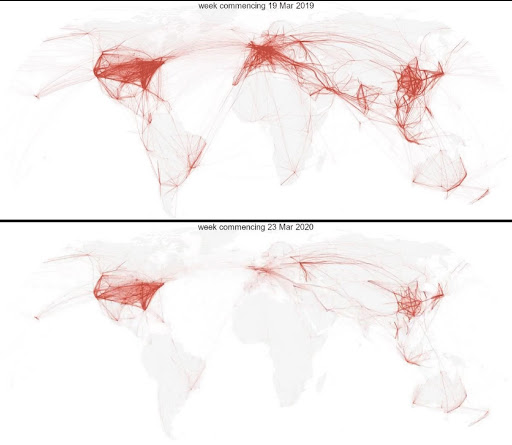

Although some might think—some do think—that humans have produced the world’s environmental devastation, ascribing this culpability broadly to all humanity obscures the fact that the profits and burdens of an extractive system are reaped and born more heavily by some humans than others (Roberts 2001). The algorithmically-driven intensity of social media only amplified the sense of panic and enormity of the pandemic (Figures 6 and 7). How does this intensity potentially contribute to a narrative that suggests that this situation is being generated by individuals and experienced uniformly by all? Whose conduct evades scrutiny in a story that directs our gaze in this way? As Naomi Klein has argued, the fact that crises are tragic is not a barrier, but a boon for frontier and industrial capitalism to expand its claim on the privatization of safety and the displacement of environmental risk onto increasingly marginalized publics in the form of pollution, floods, and yes, disease (2007). Crises make people “willing to hand over a great deal of power to anyone who claims to have a magic cure” (Klein 2007, 210). Rather than imagine that the environment is the only sacrificial victim, we might ask how these systems also harm humans, but not all equally.

Figure 6

Figure 7

Affective Hope

It is precisely this unequal distribution of precarity that might explain why ecofascist explanations are simultaneously appealing and problematic. People are scared. I am scared. We know that precarity is as affective as it is material. Rather than consider crises opportunities for capitalist expansion, we might consider precarity an opportunity and a liability. Clearly, blame feels good because it takes the focus off of our own culpability in processes that generate crises, or lulls us into feeling unable to respond. But precarity might also highlight the conditions that make these events even more tragic.

Considering this crisis as affective allows us to also consider how a global pandemic that requires people to avoid close contact with each other can still come to have such intense social resonance. My hope is that it might also have political resonance. If one effect of this outbreak is its exposure of collective fear and anxiety, we may therefore understand why ecofascist explanations are so effective. An affective framework also helps us see why hope now feels essential. This is a different sort of hope than the one referenced in the beginning of this essay. That was a hope focused on the changes we have seen, real or imagined, in the environment. Instead, a different kind of hope would focus on the future and possibilities for the environment. I find Anne Allison’s evocation of hope helpful. “Forward-dawning, anticipatory illuminations of a there and then that, while not-yet-known, comes from the refusal to settle for a dissatisfying here and now. This is the notion of hope that makes sense to me,” (Allison 2012: 362).

Figure 8

Figure 9: @decolonialatlas “One week of air traffic in March 2039 vs March 2020. #flygkam” April 4, 2020

We owe it to ourselves, and the swans, to hope for a future in which individuals and corporations are held to account for the systems that are damaging our shared lives. Seizing our precarity “can also be the conditions for social change, new forms of collective coming-together, even political revolution” (Allison 2012: 349). How can we seize a revolutionary affect to redress harm done to the earth? Might the distinction between nightmare and reality, fantasy and reality be meaningfully blurry enough to inspire collective action (Edmiston 2020)? How can we best utilize the affective qualities of blame beyond the personal, ideological, ethnic, or national? A radical dream of true environmental justice would take both our fears and our fantasies seriously, harnessing feelings as equally essential to crafting a shared future.

References:

Allison, Anne. 2012. “Ordinary Refugees: Social Precarity and Soul in 21st Century Japan.” Anthropological Quarterly 85(2): 345-70.

Edmiston, Paige. 2020. “Cultivating Resemblance: Moving Strangers on the Internet to Care.” In “Pandemic Diaries: Affect and Crisis,” Carla Jones, ed., American Ethnologist website.

Garcia, Sierra. 2020. “We’re the Virus: The Pandemic is Bringing out Environmentalism’s Dark Side.” Grist, March 30, https://grist.org/climate/were-the-virus-the-pandemic-is-bringing-out-environmentalisms-dark-side/.

Klein, Naomi. 2007. The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism. New York: Metropolitan Books.

Parreñas, Juno Salazar. 2017. Decolonizing Extinction: The Work of Care in Orangutan Rehabilitation. Durham: Duke University Press.

Roberts, J. Timmons. 2001. “Global Inequality and Climate Change,” Society & Natural Resources 14(6): 501-509.

Strassler, Karen. 2020. Demanding Images: Democracy, Mediation and the Image-Event in Indonesia. Durham: Duke University Press.

Cite as: Cunningham, Olivia. 2020. “Wanting Nature to Strike Back: Apocalyptic Dreams for a Pandemic.” In “Pandemic Diaries: Affect and Crisis,” Carla Jones, ed., American Ethnologist website, May 20 2020, [https://americanethnologist.org/features/pandemic-diaries/pandemic-diaries-affect-and-crisis/wanting-nature-to-strike-back-apocalyptic-dreams-for-a-pandemic]

Olivia Cunningham is an MA student in Anthropology at the University of Colorado, Boulder planning to conduct research on environmental justice and natural disasters. She can be reached at Olivia.Cunningham at colorado.edu.