A central tenet of Islamic practice holds that reading the Qurʾan is an act of devotion that will be rewarded by Allah. Although this belief is widespread in Indonesia, reading the Qurʾan has traditionally been conducted in religiously designated spaces, such as Islamic boarding schools (pesantren), rather than shared public spaces. Since 2013, this pattern has changed. Muslims visibly reciting the Qurʾan have now become common, from verandas of campus mosques, to buses, trains, and public squares.

Young Indonesians reciting the Qurʾan in a public park in Jakarta. (Photograph by Eva Nisa)

Facilitating this turn towards Qurʾanic reading as pious self-discipline is the One Day One Juz (ODOJ) movement. This semi-virtual Qurʾanic movement was officially launched in 2013. It was founded by activists from Tarbiyah, a Islamist movement which began in 2004 and which was inspired by the founder of the Muslim Brotherhood of Egypt, but which remains separate from the Tarbiyah movement. Since its launch, ODOJ has rapidly expanded its influence to reach Muslims from diverse ideological affiliations throughout Indonesia. ODOJ is now seen by its members as enabling Muslims from diverse religious affiliations to become closer to the Qurʾan. This includes those who attach themselves to either of the two biggest moderate Muslim mass organisations in Indonesia—which generally do not support Tarbiyah’s Islamist political agenda—the traditionalist Nahdlatul Ulama and modernist Muhammadiyah.

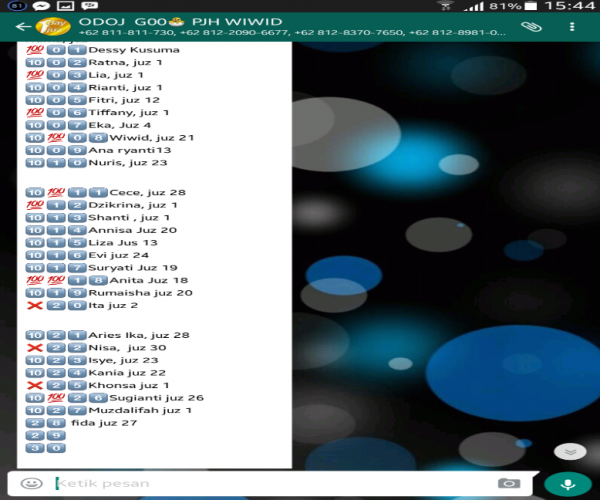

ODOJ aims to cultivate a culture of reading one part (juz) of the Qurʾan daily. Members (ODOJers) are required to report their reading progress in hourly increments through WhatsApp groups. Each group consists of thirty members who collectively aim to read the entire Qurʾan, consisting of thirty parts, daily. To date, ODOJ has 3,124 female and 979 male WhatsApp groups, totaling 123,090 members. This makes it both the largest of the online Qurʾanic reading communities, as well as the oldest. It shares features with offline recitation movements that also aim to cultivate dedication through the act of reading (Gade 2004). These include the goal of dakwah, or proselytizing through visible piety, which requires discipline for which the rewards are both personal and social. As Ricky Adrinaldi, chairman of ODOJ, said:

The basis of ODOJ activities rests in the obligation to recite the Qurʾan for all Muslims mentioned in the Qurʾan and Hadith (saying of the Prophet Muḥammad). A Hadith asks Muslims to recite the entire Qurʾan in one month’s time.

However, reading all 604 pages of the Qurʾan monthly is challenging for the majority of Indonesian Muslims who do not speak Arabic, especially when there is no driving force to motivate them. As Fahira, a 22-year-old university student, said:

To be honest, before joining ODOJ, I never finished reading the Qurʾan once in my life. ODOJ has brought a miracle to me! Every month now, I can experience khatm (finishing reading the whole Qurʾan), because of ODOJ.

As a truly social network, ODOJ, enables Fahira to collaborate with, encourage and support other readers to realize the teachings of the Prophet. She described feeling fortunate to have fellow ODOJ members help her accomplish a cherished goal.

ODOJ WhatsApp group. (Photograph by Eva Nisa)

Every group is managed by an administrator, who is helped by a PJH/Penanggung Jawab Harian (Person in Charge of Daily Activity). The PJH is responsible for the daily activities of their group and the role rotates among members. She or he greets and sends reminders to conduct the tahajjud prayer, the recommended night prayer performed before dawn. Throughout the day, the PJH sends reminders and instructions, such as dividing the parts of the Qurʾan, reminders to read, rewarding early finishers, and updating progress.

Although it was born from the zeal of Tarbiyah activists, in practice ODOJ participation is highly flexible. Anyone who is committed to participating can become a member, and if participating feels unpleasant or difficult, members can simply withdraw without notice or retribution. This flexibility is evident in particular WhatsApp groups’ traffic, which fluctuates. As Afina, a 33-year-old ex-ODOJer, said:

Initially, I felt blessed being part of ODOJ family… As time passed, however, I could not keep up with the rules. I decided to quit.

To both maintain and increase its profile, ODOJ elites are keen to ensure that their constituents, who are mainly Indonesian youth, remain engaged and enjoy participating. ODOJ’s self-reflexivity is evidenced in the way elites frame their dakwah as voluntary and pleasurable. They worry that the online format makes it easy for members to join and withdraw, much as scholar Merlyna Lim has argued, that “social media activism generates many clicks, but little sticks” (2013:646). To deepen members’ sense of attachment to the virtual community, ODOJ organizers coordinate offline activities, which they feel will generate a sense of fun and belonging and are designed to engage the minds and hearts (ta’lif al-qulub) of constituents. These events are consciously aligned with youth culture.

ODOJers and their offline activity called Nonton Bareng (loosely translates as watching films together). (Photograph by Eva Nisa)

For example, on November 13, 2016, 75,000 mostly young Muslims attended the Olimpiade Pencinta al-Qurʾan (Olympiad of Lovers of the Qurʾan) in Bekasi. Promoted as an example of a “Modern Islamic lifestyle,” the event featured non-Indonesian celebrity Qurʾanic reciter, Fatih Seferagic, a German-born Bosnian national and resident of the United States. His European-US-Muslim identity lent an air of cosmopolitaneity to the day, which featured concerts, theatrical performance and joint prayers.

ODOJers during the Olympiad of the Lovers of the Qurʾan. (Photograph by Eva Nisa)

The energy on display at this event conveyed a unique feature of the ODOJ movement: its blend of discipline and flexibility. As an online dakwah movement, the Tarbiyah origins of the ODOJ board are visible in the religious messages they send which members selectively heed or ignore. As Namira, a 32-year-old ODOjer, says:

I do not really read the messages posted by the ODOJ board, because for me ODOJ is to remind me to read the Qurʾan, not to read religious messages (from the ODOJ board) which might be different from the way I understand Islam.

Many ODOJers share Namira’s opinion, particularly because they have diverse religious affiliations ranging from traditionalist, modernist, and conservative to ultra-conservative. Members recognize that the religious understandings upheld by ODOJ elites differ from their own understandings of Islam, yet they utilize the community to enhance their commitment to daily reading. No matter their backgrounds, members share the belief that personal challenges can be resolved through Qurʾanic recitation.

The popularity of ODOJ signals how Indonesia’s dakwah landscape has witnessed a Qurʾanization of social media. I argue that the fundamentally flexible nature of social media involvement has shaped the ODOJ experience for members, allowing them to reject or accept theological content as suits them. Rather than demand uniform orthodoxy across the community, the ODOJ experience instead focuses on maintaining a sense of intimacy and constancy by connecting individual members with each other throughout the day. This intimacy facilitates a sense of belonging that makes participation appealing for social, rather than ideological, reasons.

References cited

Gade, Anna M.

2004 Perfection Makes Practice: Learning, Emotion and the Recited Qur’an in Indonesia. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

Lim, Merlyna

2013 Many Clicks but Little Sticks: Social Media Activism in Indonesia. Journal of Contemporary Asia 43(4):636-657.

Cite as: Nisa, Eva. 2017 “The Allure of “One Day One Juz”” In “Piety, Celebrity, Sociality: A Forum on Islam and Social Media in Southeast Asia,” Martin Slama and Carla Jones, eds., American Ethnologist website, November 8. http://americanethnologist.org/features/collections/piety-celebrity-sociality/the-allure-of-one-day-one-juz