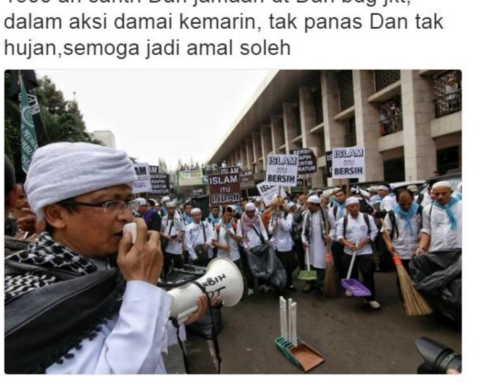

The popularity of social media in Indonesia, combined with the rise of political Islamism in recent years, are changing the ways in which people engage with religious matters in the world’s largest Muslim country. One significant change is the way that religious and political figures incorporate a combination of online and offline audiences in maintaining their public authority.

Take the entrepreneur, peace activist and senator Fahira Idris. Born in 1968 into Indonesia’s political and religious elites, Fahira’s father held several ministerial posts, while her late mother was the daughter of a former chairman of the Indonesian Ulema Council (MUI). Fahira was an early adopter of Twitter and other social media. In 2010 she was voted “The World’s Most Inspiring Tweeter” in an international poll. The tweet credited with establishing her reputation was addressed to the Islamic Defenders Front (FPI), a hardline group often linked to violent incidents. It read (our translation): “Dear FPI, is that how Islam was taught by the Prophet Muhammad?”

A recent picture of the Indonesian entrepreneur, peace activist and senator Fahira Idris. Source: Twitter. https://twitter.com/senatorjakarta

This tweet was widely interpreted as a reference to a recent violent attack, reportedly by the FPI, on a Batak Christian Protestant Church (HKBP) congregation in West Java. It sparked intense debate online between supporters of Fahira and the FPI. Fahira posed an open question, channelling what she called “the magic of Twitter” (Kristanti 2010) by asking if any of her 260,000 followers knew the address for the FPI national headquarters, information that was not public. She quickly received multiple responses offering the address, as well as other tweets advising caution (Patung 2010).

The exchange led to a high profile meeting between Fahira and Habib Rizieq, the FPI leader, at the FPI headquarters in central Jakarta. On arrival, Fahira handed Habib Rizieq a printed copy of over 1,200 emails from people across Indonesia, including victims of FPI linked violence, with comments and questions for him. In the meeting, Fahira stressed the importance of dialogue and the rule of law in a multi-faith society like Indonesia’s, and insisted that “Islam is a religion of peace” (Suara Pembaruan 2010).

Two viral arenas

The Fahira vs. Habib Rizieq controversy is a textbook example of two Turnerian “arenas.” Victor Turner defined an arena as “a bounded spatial unit in which precise, visible antagonists, individual or corporate, contend with one another for prizes and/or honour” (Turner 1974: 132-133). In an arena nothing can be left unsaid or “merely implied” (1974: 134). Rather, “all actors drawn into the drama […] must state publicly where they stand on the dispute at hand” (Postill 2011: 96).

When Fahira publicly interpellated FPI on Twitter, Habib Rizieq and his inner circle felt they had no option but to respond. Remaining silent would have meant losing face. Agreeing to see Fahira in person when she publicly announced her intention of meeting with them was the only reasonable choice to make. As a result, two arenas were assembled in rapid succession: one on Twitter, the other face to face. Overnight Habib Rizieq and Fahira became “precise, visible antagonists” vying for the hearts of minds of Indonesia’s vast Muslim population at a time of heightened inter-faith tension.

Turner argued that arenas come in many different forms: “[a] political or legal arena may range from an actual battlefield to the setting of a trial or verbal debate” (1974: 133). In the Fahira vs. Habib Rizieq case, each of the two arenas afforded these political actors a distinct set of communicative possibilities: while their in person encounter offered a richer repertoire of verbal and non-verbal social cues and immediate feedback, Twitter presented ordinary citizens with an opportunity to participate in the debate and the prospect of the issue going viral – which it did.

This episode illustrates how Twitter has come to function as a central site for short-lived arenas within Indonesia’s increasingly politicized religious space. In other words, this immensely popular platform has become a highly visible stage where public figures are compelled to unambiguously declare their stance on a current religious issue.

But what makes a Twitter arena come into being and go viral? Three factors appear to be crucial: the timing of the initial challenge, the core societal problem it addresses, and the public standing of the lead actors drawn – or dragged –into the arena.

First, the timing of Fahira’s now famous “Dear FPI” tweet was significant, as it came immediately after the alleged FPI assault on the Protestant congregation. With tempers riding high, Fahira’s rhetorical question about the Prophet Muhammad struck a chord with moderate Indonesians and was widely retweeted. The impact came as much from the content of the tweet as from the fact that Fahira had dared to confront an intimidating organization, generating a David vs. Goliath scenario.

Second, most current affairs are in fact recurrent affairs, for they address unfinished business within a social space or society. In Indonesia, one political problem unresolved since independence in 1945 is the relationship between Islam and the state. In terms of Turner’s social drama theory, the FPI attack was a breach in the established order of things; the first stage in a social drama triggered by Fahira’s tweet that brought out into the open this perennial national issue. There followed a crisis phase in which Habib Rizieq sought damage control. In effect, he was reluctantly acknowledging the state’s monopoly over the means of physical and symbolic violence. This led to a protracted phase of Turnerian re-integration between Fahira and Habib Rizieq, a phase that continues to this day, rather than a rupture or schism – the other possible outcome – between them.

The third crucial factor in the making of a viral arena is the standing of the main actors involved. Fahira’s entrepreneurial success and religious elite ancestry, together with her social media savvy, were equally instrumental in establishing her credibility as an FPI interlocutor. Similarly, Habib Rizieq was also known as a controversial “hardliner’ with a large following across the archipelago. Differing in their life trajectories and location within the country’s religious space, Fahira and Habib Rizieq represent a new genre of religious actor familiar to anthropologists of religion around the world. New religious mediators exploit the opportunities afforded by emergent media to further their ambitions in competition and/or cooperation with an incumbent religious class.

References Cited

Kristanti, E.Y.

2010 “Saya Tidak Takut FPI, Karena Saya Benar”, Viva.co.id, 30 August 2010, http://fokus.news.viva.co.id/news/read/174089-tweeter-paling-inspiratif

Patung

2010 Top Tweeter: Fahira Idris. Indonesia Matters, 30 August 2010, http://www.indonesiamatters.com/10721/fahira-idris/

Postill, John

2011 Localizing the Internet: An Anthropological Account. Oxford: Berghahn.

Republika Online

2016 Senator DPD vs Aktivis JIL, Fahira: Akhmad Sahal Ingin Pendukungnya Bully Saya, 17 March 2016, http://nasional.republika.co.id/berita/nasional/umum/16/03/17/o46ek6377-senator-dpd-vs-aktivis-jil-fahira-akhmad-sahal-ingin-pendukungnya-bully-saya

Suara Pembaruan

2010 Fahira Fahmi Idris Islam Mengajarkan Damai’ 22 September 2010 http://www.suarapembaruan.com/home/fahira-fahmi-idris-islam-mengajarkan-damai/74.

Turner, Victor W.

1974 Dramas, Fields and Metaphors: Symbolic Action in Human Society. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Cite as: Postill, John and Leonard Chrysostomos Epafras. 2017 “Tweeting Religion in Indonesia: When Political Arenas Go Viral” In “Piety, Celebrity, Sociality: A Forum on Islam and Social Media in Southeast Asia,” Martin Slama and Carla Jones, eds., American Ethnologist website, November 8. http://americanethnologist.org/features/collections/piety-celebrity-sociality/tweeting-religion-in-indonesia