Social media may create narrow communities of fellowship, but they can also introduce esoteric knowledge to broader communities. In this essay, I trace the rise of a nationally popular Muslim preacher in Indonesia, Usman Pateha, to argue that his status cannot be separated from the rise of Indonesian social media in the past decade. His personal biography illustrates the powerful intersection of religious reform and digital life.

Born in 1983 in Ujunge, a small village about 250 kilometres from Makassar, the capital city of South Sulawesi province, Usman might have lived a life far from fame or cities. He might have led a successful professional life like most of his mentors, renowned within Bugis society and the Islamic organisation As’adiyah that was established and remains centered in Wajo Regency, but committed to face-to-face communication. Instead, he has become one of a genre of preachers known as “ustadz celebrity.” Usman went to elementary and high school at Pesantren As’adiyah, the largest and one of the oldest Islamic boarding schools (pesantren) in the province. He then earned his undergraduate degree in Islamic Law from the Islamic College of As’adiyah and participated in the As’adiyah’s Young Muslim Scholar Training Program. He returned to his alma mater to teach junior high school. Fulfilling an obligation of As’adiyah membership to preach to the Muslim community at large, Usman became an active ustadz or dai (Islamic preacher), traveling regularly across and outside South Sulawesi to give inspiring religious talks, or ceramah. Circulating within the regional and national network of As’adiyah alumni, Usman became known outside of his home province. His mobility was familiar to many of his followers, because Bugis ethnicity has historically been synonymous with movement throughout the archipelago. Yet even his popularity as a speaker during Ramadan and other events in the religious calendar in As’adiyah schools and mosques kept him within a largely Bugis and As’adiyah community.

Unlike most of his fellow preachers, however, Usman established a national following, due to a combination of media forms. In June 2016, the national television station Kompas TV invited him to join a select group of young preachers to deliver a short ceramah as part of the station’s Ramadan program. Six months later, he was hired by ANTV, another national television station, to become one of the regular speakers in its religious program entitled “Cahaya Hati” (“Light of the Heart”).

Usman being videotaped by KompasTV Discussing “The Meaning of Idul Fitri,” posted on his Facebook account.

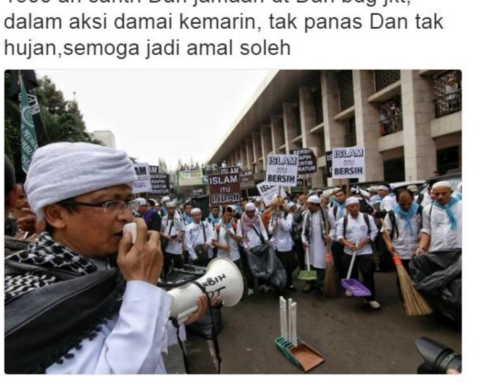

Appearing on national TV stations and becoming a celebrity preacher is rare for most preachers, including for young ustadz from As’adiyah. Yet circulation within limited religious circles has been the route to national fame of the most prominent preachers in Indonesia, who rose to fame first through preaching at majelis taklim (religious study groups) at local or provincial levels. As James Hoesterey has argued, Aa Gym, Indonesia’s top celebrity preacher in the 2000s, first became renowned by establishing a pengajian (religious teaching) program at his own boarding school (2015). More recently, social media have been a key feature in the generation and circulation of religious reputation. Ustadz Muhammad Nur Maulana, a graduate from a small pesantren in north Makassar, became popular as an entertaining, smiling and friendly preacher or “ustadz gaul” (“easy going preacher”). He has hosted a daily religious show “Islam itu Indah” (“Islam is Beautiful”) since 2009 on the national station TransTV. Until his TV show, he had spent 20 years visiting followers’ homes and serving multiple mosques among mosques in South Sulawesi and eastern Indonesia. A single sermon, uploaded to YouTube, was watched by over 100,000 viewers led TransTV to offer him a daily TV show.

Similarly, Usman’s use of Facebook was central to his national rise to prominence. His frequent posts and likes on Facebook led to his KompasTV invitation. ANTV invited him to create “Light of the Heart” after consulting a network of seven alumni from Pesantren As’adiyah who had prior contracts. Yet even their recommendations were informed by social media, because they needed references of Usman’s expertise and performance. In addition to speaking to other alumni and followers personally, they consulted his Facebook pages. “My fellow pesantren alumni first learned about my most current ceramah from Facebook and then recommended me for the job on ANTV,” explained Usman.

Usman recalls that when he joined Facebook in 2013, he simply wanted to keep in touch with his friends, particularly with his fellow As’adiyah classmates. He soon found it was a fun resource for his own sermons, gleaning inspiration, stories and jokes from fellow preachers’ Facebook walls. Facebook messenger soon became the method through which mosque communities invited him to visit them. These successes led him to post frequent updates on his religious activities, further amplifying his reputation. He began to link his Facebook account to his YouTube channel where he posted videos of his sermons. The content, and the varied settings, of the sermons underscored his reputation as a trusted leader with a large community of followers, online and off. As one of his female Facebook followers commented on a video, “Salam [Greetings], thanks God dear Ustadz, we are a big family in East Kalimantan, particularly in Samarinda, whenever we are longing for your voice we just open YouTube [to watch your video]. Then we feel our longing for your religious speech has been cured”. Today, his Facebook postings display his photos and videos in delivering speeches when being video-taped by ANTV in Jakarta, when performing the hajj and little hajj (umrah) in Mecca and Medina, and when promoting the travel agent for hajj and umrah based in Sengkang where he was hired as a religious consultant and guide.

Usman’s experience exemplifies the dramatic change in some preachers’ fortunes in Indonesia. For his mentors’ generation, the most respected, senior and therefore in demand Islamic scholars only became the leaders of As’adiyah by election of the top board members. Once elected, they would and still expect speaking invitations to be relayed in person. Telephone invitations were considered impolite and typically refused. By contrast, for Usman’s generation, social media have provided a way to connect directly with followers across the country. For him and his fellow celebrity preachers, his religious authority is fundamentally fused with his online fame. Like earlier preachers, his audience contributes to his reputation. But unlike earlier preachers, his audience reaches far beyond his immediate social network.

Usman Pateha giving a short religious lecture on ANTV, a national television station, here posted on his Facebook account.

References Cited

Hoesterey, James B.

2015 Rebranding Islam: Piety, Prosperity, and a Self-Help Guru. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press.

Cite as: Halim, Wahyuddin. 2017 “Paths to Celebrity Status: The Significance of Social Media for Islamic Preachers from South Sulawesi” In “Piety, Celebrity, Sociality: A Forum on Islam and Social Media in Southeast Asia,” Martin Slama and Carla Jones, eds., American Ethnologist website, November 8. http://americanethnologist.org/features/collections/piety-celebrity-sociality/paths-to-celebrity-status