The French system of asylum is steeped with liquid metaphors. Scholars have highlighted the ways in which demographers, politicians and media have long tapped into hydraulics and hydrology to describe migration (Le Bras 2016: 35).1 Migration is thus often posed as a “flow.” Within the reserve of liquid metaphors that permeate the French system of asylum, fluidity (fluidité) holds a particularly prominent place. Yet contrary to Zygmunt Bauman’s (2000) portrait of “liquid modernity”—of “a liquid reality that we cannot control, that slips through our fingers and is no longer ‘manageable’” (Bordoni 2016: 287)—the language of fluidité present in French public management stages a kind of rationalised and efficient control. In technocratic language, fluidité is key to order.

I first became aware of fluidity talk when I began my fieldwork in this 14-floor emergency shelter, located on the outskirts of Paris, France.

The Alpha emergency shelter. Photo credit: Tessa Bonduelle.

The shelter principally housed asylum seekers. In France, the legal-administrative status of “asylum seeker” designates a person who has officially declared their intention to submit an asylum application at the closest Préfecture.2 In theory, once they have done so, asylum seekers are legally entitled to shelter, to the social support services embedded within shelters, to healthcare and to a meagre state-provided allowance, throughout the asylum process.3 Most of this shelter’s asylum-seeking residents were technically designated as hommes isolés (isolated men). Bureaucratically, they were considered as migrating alone, without their families.4 The shelter also housed some families: 28 in total during my fieldwork, or roughly 100 individuals. But in this 400-bed shelter, hommes isolés were the numerical norm. Close to half of the hommes isolés were Afghan. Another fifth were Sudanese. The others came mostly from Eritrea, Somalia, Guinea, Mali, Cote d’Ivoire.

The shelter was run by a non-governmental “operator” I call Alpha. “Operators” are French associations (not-for-profit organisations) that respond to state calls for tenders to secure contracts for a variety of social work projects—elderly care, job seekers support, the sheltering of asylum seekers, etc. But in becoming state operators, associations bind themselves, contractually, to state logics, including logics of efficiency.

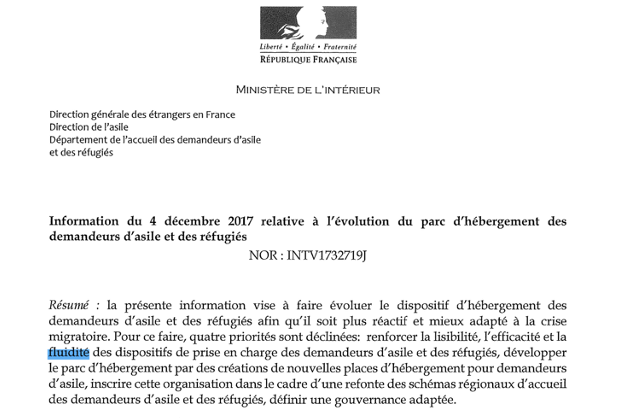

Within the Alpha shelter, I was struck by the efficiency logic undergirding fluidity talk. Backed by shelter occupancy data, Alpha management had to show civil servants that their shelter operated “fluidly”: that the stream of asylum seekers flowing in also flowed out of the shelter. To better understand the efficiency imperatives at play in the Alpha shelter, I turned to state documents—laws, financial and operational reports, calls for tenders, and implementation memos. For example, this 2017 Ministry of Interior memo, which ordered the evolution of the French shelter system for asylum seekers and refugees “so that it is more responsive and better adapted to the migration crisis” (Ministère de l’Intérieur 2017: 1).

The preamble to the December 4th 2017 Ministry of Interior memo that actualises changes to the sheltering system. Memos such as these are circulated to French préfets (Prefects)5 and to key public institutions, such as the French office for immigration and integration (the OFII), which then apply the changes outlined within. Notice that fluidité (highlighted) is one of the top priorities.

In documents such as this, fluidité appeared as a perpetually frustrated ideal. The asylum system was in fact not fluid.6 A fluid asylum system had to be instituted to fulfil state imperatives of border and budget efficiency.

Drawing upon liquid metaphors, state documents portrayed the asylum system as having to manage a constant stream of bodies, flowing into France. This stream of bodies needed to be fluidly funnelled into another stream: the asylum process. Most importantly, the stream of bodies needed to flow out of the asylum system at the end of the asylum process. Out to the generalist social welfare system and “normal” life in France (for those successful in their asylum claim). Or, for those unsuccessful in their claim, out of France. There could be no bottlenecks and no stagnation: these were a threat to the efficiency of the border.7 At one steering committee meeting on emergency shelters at a Préfecture, I heard civil servants describe the system as “embolised” by those who had already received a response to their asylum claim. These refugees or asylum rejectees “clogged” shelter spots designed for those in the process of seeking asylum. In other words, social services aimed for one category of migrant public (asylum seekers) had to be terminated when these “beneficiaries” changed status (becoming a refugee or an asylum rejectee). Public funds needed to be used efficiently.

The Alpha emergency shelter was a product of state attempts to create a fluid asylum sheltering system. It housed several different types of emergency shelters, including a CAES of 140 beds for men only. The CAES—a centre d’accueil et d’examen de situation (centre for reception and the examination of administrative situations)—was born out of the December 4, 2017 Ministry of Interior memo. It was envisioned as the point of entry into an efficient and fluid asylum system. It was because of this vison that the CAES was widely referred to by those in the field as the “triage centre” of the asylum system.

At regular intervals, men living in encampments along Paris’ northern belt were “evacuated”: corralled by French riot police onto awaiting buses to be transported to a CAES. Upon arrival at the CAES, these “evacuated” men went through a registration process that was technically referred to by Alpha staff and state civil servants as an “inclusion.” The aim of the CAES was to rapidly sort through the new arrivals’ administrative situations (pre-asylum claim, mid-asylum process, post-asylum decision) and “orient” them, depending on their status. This meant helping those pre-asylum claim to submit their asylum application and then facilitating the “transfer” of all those now in the process of seeking asylum to longer-term emergency shelters outside of Paris.

The dining room space in which “inclusions” were carried out at the Alpha shelter. Imagine a table in the left corner with two laptops, precariously connected to the ethernet and the nearest power sockets, and a portable scanner ready to scan administrative documents. Imagine also several other tables occupied by twenty-or-so tired-looking men, waiting to be registered. During these “inclusions,” Alpha employees explained that the shelter was not a detention centre, that newcomers were free to come and go from the shelter as they pleased. They emphasised, however, that the shelter was only for those seeking asylum. Photo credit: Tessa Bonduelle.

Some of the men “evacuated” saw evacuations as an opportunity to secure shelter and support in their asylum procedure. Others—especially refugees or asylum rejectees—tried to avoid being “evacuated.” They had already been through the asylum procedure and knew they no longer had the right to shelter and support within the asylum system. They would inevitably be “triaged” out—that is, expelled from the CAES—and would have to return to the (now ransacked) encampment from whence they came. With the swift transfers of asylum seekers and the even swifter expulsions of refugees and asylum rejectees, the average stay in the Alpha CAES was ten days.

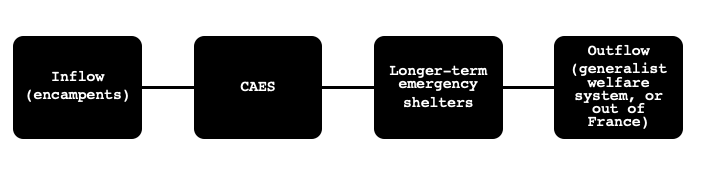

The CAES was thus imagined as the first step in an efficient chain of operations, along which the asylum-seeking input was to flow smoothly. The CAES assessed administrative situations, “triaging” the human input. Once triaged, asylum seekers were then conveyed along the chain: first to longer-term emergency shelters, then out of the sheltering system.

The imagined chain of sheltering, meant to ensure fluidity and avoid bottlenecks within the asylum system.

This efficient chain of sheltering and social support is a Fordist’s fantasy and an idealised answer to crisis: the migrant flow funnelled smoothly through the system and “managed” by non-governmental employees. The Fordist feel of sheltering was not lost on Alpha employees. Some likened their work in the Alpha shelter to an assembly-line: “un travail à la chaine.” During a coffee break, one Alpha employee compared working at the CAES to labouring on the factory floor. For this worker, “inclusions” were particularly reminiscent of assembly-line labour:

The process of admitting these groups of men into the shelter…it’s kind of industrial. We have to do it in a chain and it’s a bit stressful…like an assembly line. We make them fill out sheltering contracts, we read them the script of the “welcome speech,” we review their administrative documents one-by-one, we register their demographic data in the online database, we produce their entrance passes, we give them their room keys… It’s a chain. I did that one summer in a plastics factory and that’s what this job is like.

Like the assembly-line, fluidity tolerates no bottlenecks. The assembly line labour this employee described evoked the Fordist arrangement of industrial operations aiming for a continues flow of workpieces on a factory conveyor belt. Beyond the “inclusions”, Alpha employees repetitively undertook the same procedures for each of the “case files” they were responsible for: filling out the asylum claim dossier, completing paperwork and sending countless emails to try to secure social services and other forms of shelter when the asylum procedure came to an end. The repetition of precise and mundane tasks that consumed non-governmental operator employees in the Alpha shelter were undertaken, in part, in the name of fluid efficiency: to facilitate the flow of bodies in, and crucially out, of shelters.

But the fluid assembly-line is, in fact, a fantasy—one impossible to realise. Administrative processes designed to manage flows seldom worked as they were supposed to when applied to complex humans. Individual personal trajectories rarely fit rigid administrative categories, procedures, and sheltering rules. Further, the asylum-seeking input seldom exited the system smoothly. The lack of social housing or generalist sheltering options available meant that for many, leaving shelters at the end of the asylum procedure meant homelessness. Within this context, not only were operator employees incapable of ensuring the fluid efficiency prescribed by state documents, they were also frustrated in their desires to provide meaningful social support to shelter residents.

Notes

[1] See for example: Bernardot 2020; Holmes and Castañeda 2016.

[2] Préfectures in France are administrative jurisdictions governed by a préfet.

[3] I say “in theory” because sheltering capacities are limited. In practice, not everyone accesses shelter immediately. If a person obtains the status of “refugee” (through a positive decision on their asylum claim), a broader range of rights and resources becomes accessible to them. Notably, the right to work, the right to residency, the possibility of (one day) accessing public housing, the receipt of employment benefits. These are the rights and resources that differentiate an “asylum seeker” from a “refugee” in France. But a “refugee” is also different from an “asylum seeker” for politico-moral reasons. Current international law promotes a specific refugee “archetype” (Akoka 2011)—that of political persecution. Akoka (2011: 13), has argued that contemporary discourses around “real” refugees and “fake” asylum seekers—also alternatively labelled “economic migrants”—are a result of the enshrinement of the “occidental” image of the liberty-seeking refugee in the Geneva Convention. The “asylum seeker” thus remains a suspect figure until refugee status has been granted. They may be “economic migrants” coming to France for socio-economic reasons and attempting to dodge restrictive French immigration policies. Indeed, Fassin (2013) and Spire (2004) have argued that the official cessation of labour immigration to France in 1974 has led to subsumption of asylum under the logic of immigration control.

[4] In reality, some of these men had migrated with their families, who were also in France and seeking asylum. To increase the possibility of securing spots in shelters, families sometimes decided to split. The male head of the household would seek a spot in a men-only shelter.

[5] In France, a préfet (a Prefect) is a senior civil servant. They generally exercise the administration of the State at the territorial level (at the regional or departmental level).

[6] Within state documents, the term fluidité thus signals “crisis” within social service provision. To resort to the language of fluidité is to admit that the flow of users in and out is interrupted.

[7] Terms such as “embolism” and “clogs” give fluidity-talk a biological hue, whereby the system of asylum, and by extension the French nation-state, is posed as a body. The prolonged presence of asylum seekers, refugees, and asylum rejectees within the asylum system are thus envisioned as a concerning forms of “build-up,” potentially threatening the body of the nation-state.

References

Akoka, Karen. 2011. “L’archétype rêvé du réfugié.” Plein droit 90(3): 13. https://doi.org/10.3917/pld.090.0013.

Bauman, Zygmunt. 2000. Liquid Modernity. Cambridge, UK : Polity Press.

Bernardot, Marc. 2020. “Le Grand Bleu de Frontex. Que disent les métaphores liquides des politiques migratoires européennes ?” In L’agenciarisation de la politique d’immigration et d’asile face aux enjeux de la ‘crise des réfugiés’ en Méditerranée, edited by Rostane Mehdi, 17–26.

Bordoni, Carlo. 2016. “Introduction to Zygmunt Bauman. ” Revue Internationale de Philosophie 277(3): 281–89.

Fassin, Didier. 2013. “The Precarious Truth of Asylum.” Public Culture 25(1): 39–63. https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-1890459.

Holmes, Seth M., and Heide Castañeda. 2016. “Representing the ‘European Refugee Crisis’ in Germany and beyond: Deservingness and Difference, Life and Death. ” American Ethnologist 43(1): 12–24.https://doi.org/10.1111/amet.12259.

Ministère de l’Intérieur. 2017. “Information Du 4 Décembre 2017 Relative à l’évolution Du Parc d’hébergement Des Demandeurs d’asile et Des Réfugiés.” https://www.gisti.org/IMG/pdf/cir_2017-12-04_1732719.pdf.

Spire, Alexis. 2004. “Les Réfugiés, Une Main-d’œuvre à Part? Conditions de Séjour et d’emploi, France, 1945-1975.” Revue Européenne Des Migrations Internationales 20(2): 13-38. https://doi.org/10.4000/remi.963.

Tessa Bonduelle holds a PhD in Anthropology from the University of Toronto. She currently teaches at Université Gustave Eiffel in France. Her work focuses on welfare arrangements within Europe, exploring the social-political conditions and futures that different welfare arrangements materialize.

Cite As: Bonduelle, Tessa. 2022. “A Fordist fantasy? Managing fluidity in the French asylum system”, American Ethnologist website, 21 December 2022 [https://americanethnologist.org/online-content/essays/a-fordist-fantasy/]