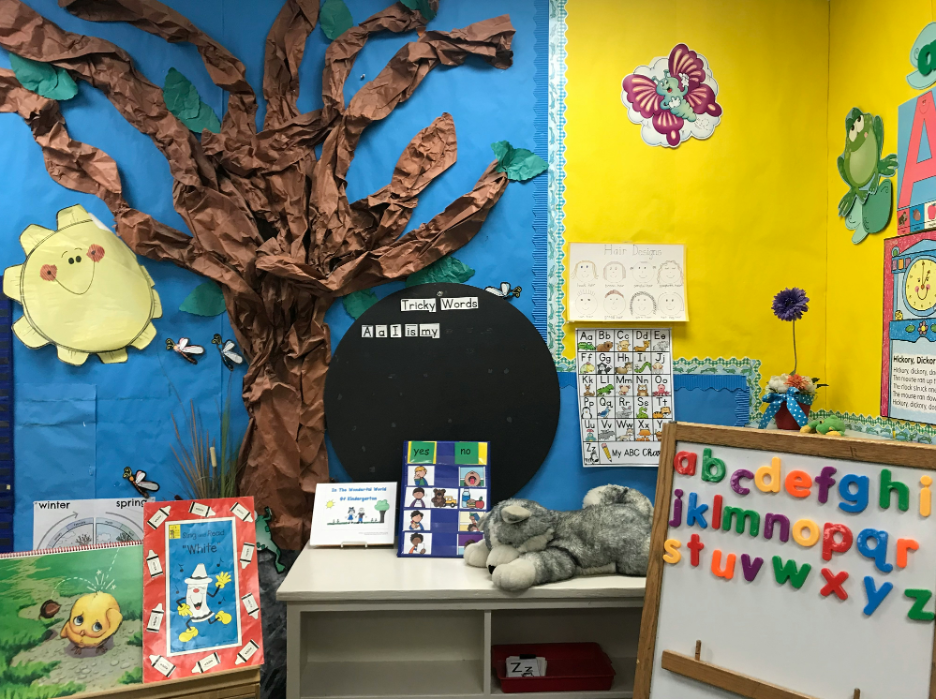

Photo by Monica Sedra on Unsplash.

It was supposed to have been a good day. Over breakfast, Du had told me all about the story she’d written for her First-Grade writer’s workshop. It starred a kid who’d invented an amazing pen that concealed a skeleton key, dispensed chocolate milk, and could only write the truth. I expected to see a smile plastered on her face when I met her on the playground after school. Instead, she wore a scowl. Forgoing our customary afterschool hug, she pulled a crumpled sheet of paper from her pocket and shoved it in my hand. Another pink slip. The fourth in three weeks.

“What happened this time?” I asked.

“Ms. Nancy hates me.” She insisted.

“Really?”

“I was trying to stop Miguel from stealing but, again, I’m the one who’s in trouble.”

I looked at the paper. Three boxes were checked. Below each was a cartoon rendering of a common elementary school infraction: 1) touching the belongs of others without permission, 2) speaking unkindly to a classmate, and 3) disrespecting a teacher. A typed statement below instructed me, “the offending child’s parent or guardian,” to “discuss the incident with the child” and to “work with him or her to select the solutions they will undertake to resolve the conflict.”

I was expected to guide Du in selecting at least one box to check on the reverse side of the form. Each indicated an action like: 1) develop a plan for mindfully cooling down when upset, or 2) repair or clean damaged property. Because school officials imagined that the “offenders” taking this document home to caregivers would not yet have mastered reading, each option was also accompanied by an illustration.

But Du, who had not yet turned five, could read.

“Notice there isn’t a box for ‘Tell your side of the story’? And there’s no box for ‘Receive an apology from your teacher?’.” She complained, “This slip isn’t fair.”

“Do you wanna tell me what happened?”

“Adam and I are the only kids who ever get pink slips. That’s all there’s to say.” (In second grade, Adam would be recognized as having autism; Du would always be the only kid in her elementary school class with tight curls and cocoa skin.)

Du had brought home this pink slip as the first of two articles I’d written for American Ethologist about institutional paperwork was being readied for publication. The article discussed how, in disciplinary institutions like prisons and schools, documentation can become both a source and a site of structural violence (Drybread 2016). Writing it had made me deeply aware of how seemingly mundane documents can unintentionally convert the personal prejudices of the document’s author into institutional facts that have lasting consequences for the subject of the document. Given that in the U.S., Black students are likely to be repeatedly sanctioned for “challenging” behaviors that white students are not disciplined for at all, I was concerned that the pink slips Ms. Nancy was sending home would eventually add up to an institutional portrait of Du that would blind future classroom teachers to her intellectual potential. I was also worried that Du might eventually internalize the image of her that Ms. Nancy had constructed with the mountain of pink slips. After all, several studies have shown that once young children are labeled “bad” by educators, this label is likely to influence their behavior and to shape their educational experiences (Kennedy-Lewis and Murphey 2016). I wasn’t about to let Ms. Nancy convert Du into a “loud” and defiant Black girl who deserved to be pushed out of school.

My knee-jerk reaction was to attack Ms. Nancy for demonstrating racism. But deep down I knew that her racial attitudes didn’t much matter. Public schools in the United States tend to be anti-Black spaces (Sojoyner 2017)—even when they’re deliberately organized, like Du’s bilingual elementary school was, around a mission of social justice (Shange 2020). I assumed Ms. Nancy would be offended if I suggested we discuss the ways white women teachers have historically been recruited to “civilize” BIPOC children (Brown 2013), and I knew I was powerless to single-handedly put a stop to the carceral tendencies I saw manifest in her disciplinary practice. Still, I was determined to confront her about the pink slips.

But before initiating a parental intervention—or an anthropological analysis—I needed to better understand the events that had led up to the pink slip she’d sent home with Du that particular day. After an episode of Jake and the Neverland Pirates and a giant chocolate chip cookie, Du was ready to talk. She told me about how she’d seen Miguel swipe a pedometer from the afterschool program’s supply closet. She scolded him before seizing the device and returning it to its proper place. Miguel went to Ms. Nancy and accused Du of stealing. Ms. Nancy didn’t hesitate to write Du a pink slip or to warn her that if she got one more, her fifth, it would mean suspension.

“You probably should have told an adult about Miguel instead of just taking the pedometer,” I said. “But I’m proud of you for trying to do the right thing.”

“I know I was being good.” Du responded. “Miguel is the thief in this scenario; he should’ve been the one to get a pink slip.” Repeating her complaints from the playground, she added, “Ms. Nancy wouldn’t even listen to my side of the story. And there’s no place on that stupid pink slip for me to tell what really happened.”

Before this moment, I had thought that the pink slip designed by staff at Du’s elementary school to inform parents of their children’s disciplinary infractions was quite clever. It enabled students with emerging literacy to understand and respond to institutional documentation; it inspired conversation between students and their parents; and it encouraged children to take personal responsibility for actions that were harmful to school property, staff, or fellow students. Du made me realize that the agency and accountability the document promoted were, however, circumscribed by the form of the document itself.

Each time they sent a student home with a slip, teachers and staff were forced to transform the complex event that had precipitated their paperwork into an orderly story that was suitable for the institutional interventions predetermined by the document. Like other “paperwork technologies” used in disciplinary settings (Brodwin 2011: 195), the form of the pink slip itself eliminated facts and circumstances that did not accord with the limited range of information its check boxes could record. If an incident couldn’t neatly be described by one of the six pictures on the form, teachers had to choose the best approximation. Then, once a box had been checked, the corresponding infraction became an institutional reality that dictated the disciplinary interventions a teacher was expected to implement (Drybread 2022; 109; Smith 1974: 258).

Du’s biggest complaint was that the form didn’t include a box for students to check if they wanted to declare themselves innocent. She was angry that the slip gave primacy to the perspectives of teachers and staff.

Her complaints drew my attention to the ways the form reaffirmed the authority vested in these adults and allowed them to escape accountability for either escalating a minor disagreement into a disciplinary infraction or for misidentifying a rule-breaker. Thinking about it, I realized that Du had critiqued these features of the pink slip when she’d brought home her second that year. Back then, her “arch-nemesis,” Val, had kicked her in the shin when they were waiting in line to pick a book for reading time. As Val made her way back to her desk, Du stuck out a foot and tripped her. Ms. Nancy saw the trip and refused to listen to Du’s complaint about the kick. On that occasion, Du and I had agreed that even though it was unjust for Val to escape consequences for her actions, both girls were in the wrong. So, Du checked the “I will apologize to the people I’ve offended” box on the pink slip and reluctantly told Val, “I’m sorry.”

This time, Du refused to admit wrongdoing. She wanted to be praised, not punished, for protecting the afterschool program’s pedometers. Eventually, we decided that rather than checking one of the boxes on the form, she would write her narrative of the incident on the pink slip. Then, I would schedule a meeting with Ms. Nancy to voice Du’s concerns to the teacher, in the hopes we could devise a strategy for the two to better communicate in the future.

When I arrived at the meeting, a lined sheet of paper with the words “Meeting Notes” sat atop a knee-high table near Ms. Nancy’s desk. On the first line she had already written “Parent Meeting,” Du’s full name, and the date. I took a seat and waited.

Ms. Nancy breezed into the classroom and nodded hello. Before taking the seat opposite me, she went to her desk and grabbed the pink slip Du had brought back to school. She handed it to me saying, “I can’t accept this because Du didn’t check one of the solution boxes. She needs to learn to properly fill out the document.”

I explained, “She didn’t check a box because she and I agreed that the document is one-sided. It made her admit to wrongdoing when she was only trying to help enforce school rules.” I read Du’s account of the pedometer incident from the slip, then went on to explain my child’s frustration at being silenced whenever another student accused her of wrongdoing.

Each time I finished airing one of the grievances Du had previously voiced, Ms. Nancy asked, “Is that it?” So, I told her everything Du had told me about her experiences in Ms. Nancy’s classroom, including that she was angry about having her requests for help in spelling words like obnoxious and carnivorous dismissed with comments like, “Just do your best.” I spoke for a full 22 minutes. The page reserved for “Meeting Notes” was still blank when I’d finished.

“Ok, my turn,” Ms. Nancy said, picking up her pen for the first time. “I’m not even going to address Du’s academic problems because something needs to be done about her behavior.” She wrote “Du is disrespectful!” in all caps, filling two of the paper’s very wide lines. Then, she underlined her sentence three times before putting the pen down and looking straight up at me to repeat aloud the words she’d just written.

Reeling from Ms. Nancy’s attempt to turn Du’s relatively advanced vocabulary into a “problem,” I took a deep breath, held Ms. Nancy’s gaze, and waited for her to continue. She didn’t. She seemed to want affirmation, and I refused to oblige.

Of course, in Ms. Nancy’s nonverbal plea for agreement, I saw her desire to be recognized as a dedicated and capable educator. My anthropological research into the work of institutional documentation had made me aware that in recording notes of our meeting, Ms. Nancy was not only recording our exchange, but she was also creating an institutional record of her own professional competence (Drybread 2016: 412; Göpfert 2013). I hadn’t expected her to portray herself in a negative light in the meeting notes, but I was offended that she hadn’t considered a single word I’d spoken worthy of being recorded on a document that would go into Du’s institutional file. In reading about the carceral continuum linking U.S. prisons and schools (Sojoyner 2016), I’d learned that in charging Du with “disrespect,” Ms. Nancy was not objectively reporting my child’s behavior; she was recording her own emotional reaction to that behavior in a way that could have lasting repercussions for my daughter.

In the sweetest tone I could muster, I told Ms. Nancy, “You need to tear up that piece of paper so that we can start a more equitable record of this meeting, or we have to reschedule it with [the principal].”

“There’s no need for that. I’m the teacher,’ she said, invoking both institutional authority and technical expertise. “I’ll add a record of the meeting to her file, and then if you wish to discuss it with [the principal] you may do so at another time.”

Perhaps Ms. Nancy assumed that because I’m a single parent and because my abysmally low university salary qualifies my children to receive free school lunch, I wouldn’t challenge her authority. Studies have shown that students who receive free school lunch tend to face more severe consequences for disciplinary infractions than high-income students, and their parents are less likely to challenge the assessments of educational professionals (Domina et. al. 2024). She seemed surprised by my refusal to acquiesce to her authority.

“I will not let that become part of her file,” I said, gathering my belongings. I informed Ms. Nancy that I would contact the school secretary to schedule a meeting with the principal. Then I left, making sure to take the pink slip Du had written on with me. I planned to bring it, along with my own written account of my exchange with Ms. Nancy, to our next meeting.

Two days later, we met with the principal. After listening to Ms. Nancy’s complaints about Du’s behavior and my concerns that Du was being overzealously disciplined, the principal decided that she would meet with Du and Miguel to discuss the incident. In that meeting, Miguel apologized for swiping the pedometer and the principal promised Du that she would be allowed to record her version of events on this and subsequent pink slips given to her by Ms. Nancy (there were only two more that year).

The principal and I later met again, to discuss the ways that the school’s pink slip might itself reinforce carceral practices that could disproportionately harm Black and Latinx students. Following our discussion, she added a section to the form that allowed kids and their parents to introduce the student’s story into the document. A few years later, when, in the wake of nationwide BLM protests, the local school board opened a district-wide conversation about the disproportionate number of disciplinary referrals given to Black boys and girls and to Latinx boys in the district’s schools, she made sure I was invited to a discussion on rethinking the paperwork teachers at all levels of schooling used to record disciplinary referrals.

It is worth repeating that even in elementary school, Black boys and girls are more likely than other students to be sanctioned for both significant and trivial behavioral infractions (Boonstra 2021). Their infractions are also more likely to be documented in official records (Vavrus and Cole 2002). Studies have shown that the more behavioral infractions documented in a student’s record, the more likely that student is to be subject to future disciplinary practices by other educators who presume that, because the student has a disciplinary record, they are a troublemaker (Welsh and Rodriguez 2024). This suggests that rather than continuing to look outside of schools—to poverty, to family structure, to public policy—to find the elements that form the school-to-prison pipeline, scholars would also do well to look inside the folders and file cabinets that house school disciplinary records to study the form(s) these documents take. For the understandings these documents enable—and the types of accountability they require—too often cohere into a form of state action that forces Black children out of school and onto a path that is likely to lead toward criminalization.

References

Boonstra, Kathryn E. 2021. Constructing “behavior problems”: Race, disability, and everyday discipline practices in the figured world of kindergarten. Anthropology & Education Quarterly, 52, no. 4: 373-390.

Brodwin, Paul. 2011. “Futility in the Practice of Community Psychiatry.” Medical Anthropology Quarterly 25, no. 2 (June): 189–208.

Brown, Amy. 2013. “Waiting for Superwoman: White Female Teachers and the Construction of the” Neoliberal Savior” in a New York City Public School.” Journal for Critical Education Policy Studies 11, no. 2: 123-164.

Domina, Thurston, Leah Clark, Vitaly Radsky, and Renuka Bhaskar. 2024. “There Is Such a Thing as a Free Lunch: School Meals, Stigma, and Student Discipline.” American Educational Research Journal 61, no. 2: 287-327.

Drybread, K., 2022. Conjuring criminals: Sympathetic magic and bureaucratic paperwork in a Brazilian juvenile prison. American Ethnologist, 49, no.1: 104-117.

——. 2016. “Documents of indiscipline and indifference: The violence of bureaucracy in a Brazilian juvenile prison.” American Ethnologist 43, no. 3: 411-423.

Göpfert, Mirco. 2013. “Bureaucratic Aesthetics: Report Writing in the Nigérien Gendarmerie.” American Ethnologist 40, no. 2: 324–34.

Kennedy-Lewis, Brianna L., and Amy S. Murphy. 2016. “Listening to “Frequent Flyers”: What Persistently Disciplined Students Have to Say About Being Labeled as “Bad”.” Teachers College Record 118, no. 1: 1-40.

Shange, Savannah. 2020. Progressive Dystopia: Abolition, Antiblackness, and Schooling in San Francisco. Duke University Press.

Smith, Dorothy. 1974. “The Social Construction of Documentary Reality.” Sociological Inquiry 44, no. 4 (October): 257– 68.

Sojoyner, Damien. 2016. First Strike: Educational Enclosures in Black Los Angeles. University of Minnesota Press.

Vavrus, F. and Cole, K., 2002. “I didn’t do nothin’”: The discursive construction of school suspension. The Urban Review, 34, pp.87-111.

Welsh, Richard O., and Luis A. Rodriguez. 2024. “The plight of persistently disciplined students: Examining frequent flyers and the conversion of office discipline referrals into suspensions.” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 46, no. 1: 160-170.

Kristen Drybread is an anthropologist whose research examines how race and class have historically intersected in both the definition and the punishment of crime in the Americas, particularly in the United States and in Brazil. Kristen is an editor, with Donna Goldstein, of Corruption and Illiberal Politics in the Trump Era, and she has written for publications ranging from American Anthropologist to The Guardian, to Glamour.