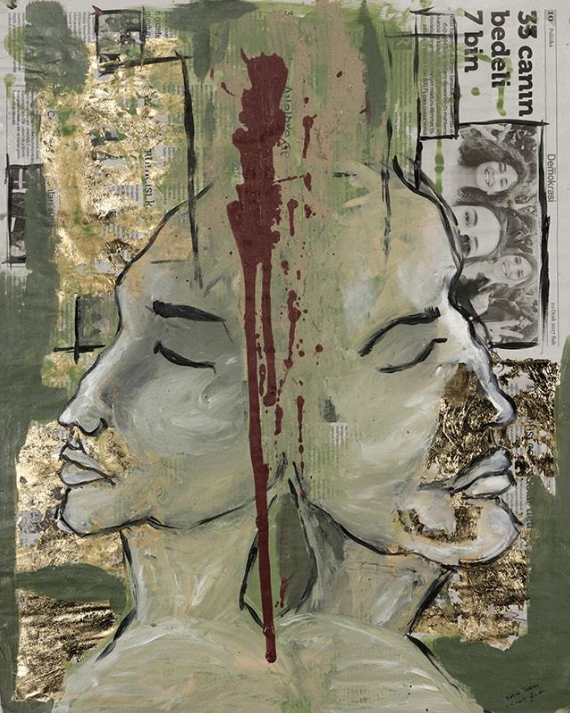

Zehra Dogan. Fugitive Times (Gold mica flake and acrylic on a newspaper page). 2017. Kedistan Collection. Reproduced by permission of artist.

At a court hearing held in 2012, the public prosecutor presented the recordings of the Kurdish political captive Torhildan’s tapped phone conversations as an evidence of his membership in an armed “terrorist” organization. Not only the content of his conversations supported this charge, the public prosecutor argued, but also the form of address he used when talking to other people on the phone: “Heval (friend) is a term commonly used among PKK (Kurdistan Workers’ Party) members to address each other.” The judge leaned toward the captive’s file and began to read one of the tapped phone conversations. Soon after, Torhildan interrupted the judge on the ground that that the inclusion of that conversation in his file violated his right to privacy. “That was a conversation between me and my social friend.” The judge glanced over the conversation and agreed to skip it. Yet the awkward term “social friend” raised eyebrows of the fellow captives in the room. Who did he count as social friend if not the other Kurdish political captives with whom they are comrades? How private is one’s privacy in a revolutionary movement where the members are immersed in the lives of each other?

The friendship developed by Kurdish captives in political wards resembles the comradeship in other revolutionary organizations where the private as the space of personal difference is disavowed in the name of forming a public in which solidarity is established across urban-rural, peasant-worker, and elite-subaltern populations (Gürbilek 2016). This utopian ideal of dismantling the public-private divide can easily lend itself into a dystopia in the hands of totalitarian regimes controlling not only how one participates in the public but also how one relates to another in the private (Arendt 1968). Although the prison life of Kurdish captives where the personal is denounced in the name of the communal carries this dystopic potential, I propose to consider the distinction between public and private not in absolute terms, but rather in terms of the degrees of privacy the captives may share, by paying attention to the forms of intimacy that they develop from within their wards.

The PKK’s incorporation of the Kurmanji word for friend, heval, into its vocabulary leaves some ambivalence with regard to the level of intimacy folded into the captives’ friendships. Heval, depending on the context in which it is used, denotes comrade, lover, or confidant. When two captives call each other heval, instead of using proper names, kinship terms, or honorific titles, it incites the kind of solidarity generally associated with “comrade.” As a form of address, it enables the captives to entertain verbal egalitarianism by establishing equality between the addressee and addresser who might otherwise be in a superior-subordinate position. With the erasure of all identifiers from conversation, heval also enables the captives to establish formal interaction so as to give and receive commands. Despite this semiotic resemblance of heval to comrade, it still retains other affectively charged meanings (love and intimacy) which may be evoked when talking about rather than talking to a friend as it was done by Torhildan in the court.

In an institution where the terms and norms of friendship are highly structured, I argue that heval hides within itself different modalities of mahremiyet (intimacy) which is achieved both despite and because of the prison administration and the commune. Coming from the Arabic root h-r-m, mahrem (intimate), it is semantically tied to other terms derived from the same root: harem (private space) and haram (forbidden). The degree of intimacy denoted by mahrem is contingent upon the demarcation of a private space to which strangers are forbidden to enter. Neither the boundaries of this private space nor the persons forbidden from entering are fixed; they change as the way in which the self is made to relate to the other changes. Among different pictures of intimacy drawn by the former captives during my interviews (2008-2018), let me here focus on one that was a product, albeit an unintended one, of the power the prison authority exercised over the Kurdish political captives through torture.

In contrast to my one-on-one interviews with former captives who narrated their prison experience either in the romantic genre or in the genre of tragedy, the stories which unfolded during my casual conversations with groups of two or more former captives revolved around the question of how they endured the difficulties of prison life in the everyday. It was neither the spectacular prison uprisings nor the infamous prison operations that colored such conversations. They rather talked about the events that were memorable in the history of their friendship, yet would fail to be counted as such in the history of the PKK. One particular conversation I had with Torhildan whose court trial I have been observing since 2009 and his former prison friend Kasım was striking in showing how the mundane practices of torture at once violated the captives’ sense of intimacy and yet facilitated intimate connections between the self and the other. If some of these violent events ended up breaking down captives and producing “traitors” in opposition to which the Kurdish political captives draw the boundaries of their friendship, others resulted in the formation of a “we” which is a part of but irreducible to the inmate population called the Kurdish political captives.

Torhildan and Kasım had been captured around the same time and stayed in the same prison throughout the 1990s. Upon their release in early 2000s, Torhildan continued working as a professional revolutionary; whereas Kasım completed his interrupted higher education in literature and then found a job as a translator. In the Winter 2018 Torhildan invited me and Kasım to his apartment for a lunch. While Torhildan was preparing the meal, Kasım and I chatted about how they had met the first time. Kasım recalled that when Torhildan was brought in 1992 to prison he still had open wounds and a few bullets in his body, and he was nonetheless taken to a torture chamber. With a discernible discomfort, Torhildan corrected Kasım that he had not been the only one tortured; the entire prison had served as a torture chamber especially from 1993 to 1994. “We saw the worst kind of torture,” he added to indicate that the pronoun of the tortured subject was not the first person singular “I” but the first person plural “we” indexing him, Kasım, and many others whose bodies were maimed in that prison.

As the conversation took these two men back to the prison days, they confirmed with each other the names of other captives who had stayed in their ward with brief notes about their whereabouts at the present. The list was so long that I could not help but ask how they could still remember those who were no longer their “comrades” in the literal sense—meaning they no longer worked for the PKK. Kasım admitted that he could not not remember them since his memories of those friends were stuck to his skin. Torhildan followed up on Kasım: “The friends with whom you were strip-searched and tortured have a qualitatively different place in your life. We had seen each other in a condition that no one else, neither your parents nor your wife, ever could. We saw each other’s utmost intimate selves (Birbirimizin en mahremini gördük).”

What is it that is seen when one sees one’s friend stripped naked and tortured? On the one hand, the tortured body attests to one’s existential vulnerability in the face of physical violence. Before and beyond the infliction of pain, torture puts the body at risk of betrayal as the tortured subject loses sovereign control over his own body (Al-Mohammad 2007; Talebi 2011). This loss of sovereignty manifests itself in various ways; one of them being forced sexual intercourse between male captives in political wards. On the other hand, the one who is forced to be present to the torture of the other experiences the act of seeing the other in pain as an act of being in pain. Reflecting on this experience, Torhildan recalled that once the prison guards burned the pubic hair of a captive in his ward. As he and other captives were watching that friend in pain, his hand inadvertently moved to his own pubic hair as if his was also on fire. What Torhildan counts in this instance as torture is his body’s simultaneous susceptibility to pain and inability to act when the torturer acts on the other’s body.

Ethnographic accounts of prisons from Northern Ireland to Turkey to Palestine show how the culmination of such instances of oppression incites large-scale prison uprisings (Aretxaga 1995; Bargu 2016; Feldman 1991; Nashif 2008). However, what they have not highlighted so well is that the comradeship between these captives might turn into intimate friendship (heval as in confidant) when the captives are made to witness their mutually constitutive bodily vulnerabilities. Collective torture entails the forced inclusion of the other in the mahrem of the self. This forbidden entrance would constitute a grave violation, as it did regarding the perpetrators, if the other has not become a part of the self who could see and feel the vulnerability of his own body through that of the other. Instead of closing in on itself, pain under these circumstances extends by moving beyond the limits of one’s body (cf. Daniel 1996; Scarry 1985). It produces new norms of intimacy.

The act of seeing and being tortured can be considered “a source of external embarrassment but that nevertheless provide insiders with their assurance of common sociality” (Herzfeld 2005, 3). The grammar of this sociality is the first person plural not because torture annihilates the self or renders personal experience generalizable. It is rather because the boundaries of the body are extended to embrace the other’s presence in the intimacy of the self. If formality is a constitutive aspect of solidarity among comrades in revolutionary movements, intimacy is its counterpart without which it would be hard to understand how these captives come to stand together against the violence of prison administrations.

References

Al-Mohammad, Hayder. 2007. “Ordure and Disorder: The Case of Basra and the Anthropology of Excrement.” Anthropology of the Middle East 2 (2): 1–23.

Arendt, Hannah. 1968. The Origins of Totalitarianism. Florida: Harcourt Books.

Aretxaga, Begona. 1995. “Dirty Protest: Symbolic Overdetermination and Gender in Northern Ireland Ethnic Violence.” Ethnos 23 (2): 123-148.

Bargu, Banu. 2016. Starve and Immolate – the Politics of Human Weapons. Columbia University Press.

Daniel, E. Valentine. 1996. Charred Lullabies: Chapters in an Anthropology of Violence. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Feldman, Allen. 1991. Formations of Violence: The Narrative of the Body and Political Terror in Northern Ireland. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Gürbilek, Nurdan. 2016. Vitrinde Yaşamak: 1980’lerin Kültürel İklimi [Living in A Shop Window: The Cultural Climate of 1980s] . 8th ed. İstanbul: Metis Yayınları. First published 1992.

Herzfeld, Michael. 2005. Cultural Intimacy: Social Poetics in the Nation-State. London: Routledge.

Nashif, Esmail. 2008. Palestinian Political Prisoners: Identity and Community. London: Routledge.

Scarry, Elaine. 1985. The Body in Pain: The Making and Unmaking of the World. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Talebi, Shahla. 2011. Ghosts of Revolution: Rekindled Memories of Imprisonment in Iran. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Cite as

Hakyemez, Serra. 2019. “Intimate Comrades Behind Bars.” In Tobias Kelly, ed., “The Intimacy of Dissent,” American Ethnologist website, April 15, 2019. http://americanethnologist.org/features/collections/the-intimacy-of-dissent/intimate-comrades-behind-bars.

Serra Hakyemez is Assistant Professor of Anthropology in the Department of Anthropology at the University of Minnesota.