How and for whom does the intimacy of family matter in political dissent? Consider this sentence a British colonial officer wrote in 1946: “He was accompanied on one or more occasions by son of about 12 years of age, dressed in English style, and speaking English.” The “he” of the sentence was Rapga Pangdatsang, a Tibetan intellectual in exile in Kalimpong, India. He was the founder of Tibet’s first political party, and an advocate of modern democracy as an alternative to Tibet’s conservative, inward-focused government. The party needed application forms and membership cards, and so together with his son, Rapga traveled to Calcutta to have these printed. His order aroused print shop employees’ suspicions. They contacted the police who agreed Rapga’s order was of concern and began to surveil him. In a “TOP SECRET” report on his political activities, W.A.B. Gardner, the Additional Deputy Commissioner of the Police, Security Control, Calcutta, authored the above sentence about Rapga and his son. Both observation and accusation, this sentence is part of a document that set in motion Rapga Pangdatsang’s eventual deportation from India for being an enemy of empire. In determining Rapga to be a dangerous political figure, Gardner also observed him to be a family man. But, what work did British officials hope for from this particular ethnographic detail?

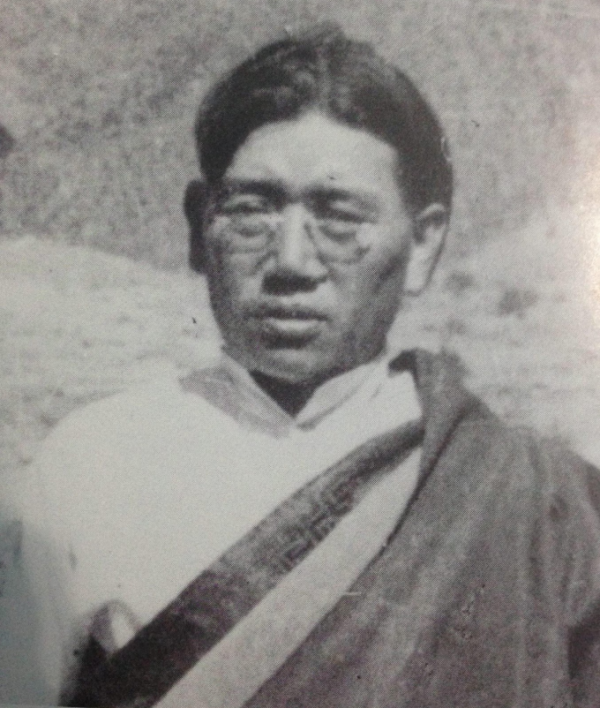

Rapga Pangdatsang.

Son, brother, husband, father, friend, rebel intellectual. Rapga Pangdatsang was all of these things. His political activism unfolded in the context of community, but not only that of his fellow exiles and dissidents. Who he was and what he politically desired were shaped, in part, by family. A decade earlier, in defense of the 13th Dalai Lama, he and his younger brother Tobgyal revolted against the Tibetan Government Army; their older brother Yamphel was held politically and financially responsible for their revolt. Two decades later following Tibet’s colonization by the People’s Republic of China, the youngest brother was officially and publicly “struggled against”—verbal and physically abused—as part of the Cultural Revolution. The Communist government forced the eldest brother to watch and witness this abuse; both died soon after. These were the three Pangdatsang brothers, powerful traders, regional leaders, and devotees of the Dalai Lama. While each brother had a distinct public persona and place in Tibetan society, as individuals they were also understood in the context of family name, power, and obligation. Thus, while Rapga’s political party was his own endeavor in partnership with like-minded intellectuals, his family status was always part of the context of his political actions.

In his introduction to this collection of essays, Tobias Kelly suggests that intimate domains such as family have been mostly overlooked in scholarship on political dissent in favor of the liberal subject and attendant notions of personhood, agency, and individual freedom (2019). Consideration of the intimate, of the relations and commitments of both kinship and friendship require analysis that precedes and exceeds a liberal (or any other sort) of individual. Instead, in some instances it is more resonant with now longstanding anthropological thinking of the “dividual,” following Marilyn Strathern’s 1988 articulation of a self who is created and situated in a network of intimate kin relations. In taking the “dividual” as a possible, and even primary self of political dissent, we enter the world of familial relations, of obligations and connections to family that are manifest and acknowledged in society. Yet in this case of Tibetan dissidents in British India, the meaning of Tibetan family relations was not necessarily understood by imperial officials.

Tibet was not colonized by the British, and thus Tibetans’ experiences with British empire were imperial but not colonial. If colonial empire was ethnographic (Cohn 1987; Dirks 2002), then imperial empire was speculative (McGranahan 2017). That is, the ethnographic effort to know colonial subjects in order to effectively rule them was merely speculative in the case of imperial subjects. In both contexts, the conceit of empire enabled claims to knowledge even when it was not actually held. As imperial subjects in British India, Tibetans’ political subjectivity was also reckoned along an additional axis: were they pro- or anti-British? Rapga was neither. His political activities did not revolve around England or empire, but focused instead on political possibility for Tibet. For British officers in India, this indifference to empire in one’s political view of Tibet was unthinkable (Trouillot 1995).

It is no surprise that governments use family ties in efforts to know, surveil, and punish dissidents. Details about the Pangdatsang brothers are sprinkled liberally throughout documents in the British imperial archives in London. The focus is narrowly on the brothers; other family members do not make appearances. This is one reason why the detail about Rapga’s son has always stood out to me. In my reading and re-reading of related files, he never appears again. Yet his political education in the hands of his dissident father would shape his life. Sonam, the archival “son of about 12 years of age, dressed in English style, and speaking English” would go on to be a beloved history teacher at a prestigious school in Kalimpong. Teacher to a multiethnic Himalayan student body, he was assigned to teach Indian history. Instead, he taught Tibetan history, and within that, as more than one of his students fondly remembered to me, all of his historical examples were from Kham, the eastern Tibetan region that was home to the Pangdatsang family. “We called him “Mr. In-Kham,” explained one of his former students, “All of his examples in class began with “In Kham….”

Imperial speculation about the condition, form, and audience of Rapga’s dissent paled in comparison to his actual project; in other words, the British got much wrong (McGranahan 2005, 2017). But in the grotesquely hierarchical operations of empire, this was not an insurmountable obstacle for imperial officials. In the absence of substantive knowledge, ethnographic detail was deployed as actionable truth. Rapga was proclaimed guilty via speculation. Ann Laura Stoler argues that the force of details in colonial writings serve to mark difference as meaningful and even explanatory: “It’s not just that details matter, but rather their placement and timing as evidentiary claims” (forthcoming). Placed in his file as evidence against Rapga, the detail about his son misses as much as it tells. For if his son Sonam’s appearance is only fleeting in British imperial archives, he is very present in Rapga’s own personal archives—his diary, newspaper clippings, and family stories. When he was deported from India, Rapga took Sonam with him on the long journey through China back to Tibet. Eventually they returned to an India no longer British where both men lived until their deaths.

Once imperial officials determined that Rapga’s political dissent against the Tibetan Government did not advance British interests, they decided that accumulated details could be converted into evidence against him. Details were made to matter so that a certain outcome would be possible. The irony is that these details were important in ways not visible to agents of British empire. As descendants of the Pangdatsang brothers consider the family’s complicated and controversial place in 20th century Tibetan history, the details of dissent and its repercussions continue to matter today.

References

Cohn, Bernard. 1987. An Anthropologist Among the Historians and Other Essays. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dirks, Nicholas B. 2002. “Annals of the Archive: Ethnographic Notes on the Sources of History.” In From the Margins: Historical Anthropology and Its Futures, edited by Brian Axel, 47-65. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Kelly, Tobias. 2019. “Introduction: Anthropological Perspectives on the Intimate Life of Dissent.” American Ethnological Society website. [Insert URL here]

McGranahan, Carole. 2005. “In Rapga’s Library: The Texts and Times of a Rebel Tibetan Intellectual.” Les Cahiers d’Extrême Asie 15: 255-276.

McGranahan, Carole. 2017. “Imperial but Not Colonial: British India, Archival Truths, and the Case of the ‘Naughty’ Tibetans.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 59 (1): 68-95.

Stoler, Ann Laura. Forthcoming. “Writing the Disquiets of a Colonial Field.” In Writing Anthropology: Essays on Craft and Commitment, edited by Carole McGranahan. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Strathern, Marilyn. 1988. The Gender of the Gift: Problems with Women and Problems with Society in Melanesia. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Trouillot, Michel-Rolph. 1995. Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History. Boston: Beacon Press.

Cite as

McGranahan, Carole. 2019. “Detail as Evidence: On Family, Empire, and Political Dissent.” In Tobias Kelly, ed., “The Intimacy of Dissent,” American Ethnologist website, April 15, 2019. http://americanethnologist.org/features/collections/the-intimacy-of-dissent/detail-as-evidence.

Carole McGranahan is associate professor of anthropology at the University of Colorado, Boulder.