2017 marks the eighth anniversary of habiblutf.net, the official website of Indonesia’s most well-known contemporary Sufi (Islamic mysticism) master, Habib Luthfi bin Yahya (b. 1947). A native of Pekalongan, Central Java, Habib Luthfi commands an expansive congregation. His monthly gatherings attract thousands of devotees ranging from government officials, members of the armed forces, Muslim scholars, to rural peasantries. Since 2000, Habib Luthfi has also led the association of Sufi orders in Indonesia. Today, Habib Luthfi’s website is accessed by 100-300,000 visitors each month. His official Facebook fan-page and Twitter account have more than 1.9 million and 61,000 followers, respectively. Far from being mere channels of communication and dissemination, however, Habib Luthfi’s social media engender negotiations over traditional forms of Islamic authority, which have become increasingly contested amidst the increasingly plural, often competing, social and intellectual formations of post-authoritarian Indonesia. The expansion of modern Islamic movements often tied to transnational Islamic networks hostile to Sufism; competing claims of authenticity of different congregations; and secular intellectual formations facilitated by modern media, schools and universities; have opened up complex and conflictual terrains, which are reproduced in and through the social media. Traditional Sufi orders and the structured hierarchies linking Sufi masters and their disciples in a relation of subservience have persistently become objects of criticism in both offline and online debates. Despite various anxieties, however, social media have afforded Habib Luthfi’s followers with new ways of responding to such challenges, including the opportunity to reproduce Sufi logics of interaction online, which although they still hinge on subservience, can no longer be characterized as straightforward submission to authority.

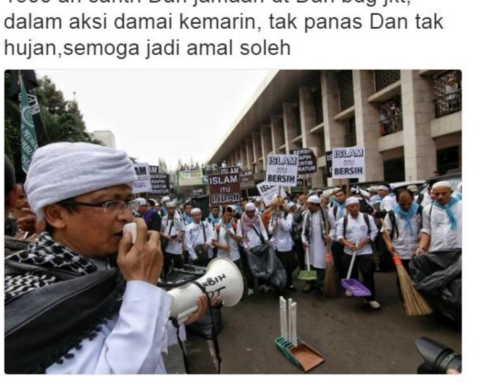

Habib Luthfi addressing his followers during his monthly gathering. (Photograph by Ismail Fajrie Alatas)

For Ahmad Tsauri (b.1985), the young disciple of Habib Luthfi responsible for the creation and maintenance of the latter’s social media presence, the internet affords new opportunities for the dissemination of the Sufi master’s thoughts among the wider Indonesian public including those skeptical of Sufism and Sufi orders. To do so, Tsauri presents Habib Luthfi not as a charismatic Sufi Master, but as an Islamic public intellectual concerned with the common good of the nation. He consciously minimizes, if not excludes, Habib Luthfi’s discourse on Sufi metaphysics, focusing instead on his civic and nationalist ideas, which are presented as “opini persuasif” (persuasive opinion) that ought to elicit responses and discussions.

Tsauri’s project, however, has also caused alarm among other disciples, particularly because Habib Luthfi himself — despite his authorization —has not been directly involved in managing, funding, or supervising his website and social media accounts. Central to their concern is the issue of authorial absence that follows when the discourses of the Sufi master are disseminated in decentered forms. Some characterize the internet, and the kind of sociality it engenders, as a source of fitna, i.e. temptation, trial, sedition, slander, “the straying of language,” “semiotic disorder” (Pandolfo 1997: 91). In their views, the kind of discursive circulation afforded by the social media, together with the absence of control, can lead to the fracturing of discourse from authorial intent, thereby aggravating the risk of fitna.

Tsauri was right in that Habib Luthfi’s social media presence would generate interest from the broader public. What he did not anticipate, however, was the ensuing increase of internet usage among members of Habib Luthfi’s congregation, facilitated by the availability of affordable China-made smart phones and the decreasing price of internet data plans due to the increasing competition among phone service providers. Members of Habib Luthfi’s congregation use the internet to observe their master’s latest photos, read his newest posts, and maintain spiritual connection with the master. The term that kept coming up during my conversations with them was rabiṭa (Arabic: binding), a Sufi term for a technique of visualization of keeping the image of the master in the disciples’ heart. Rabiṭa supplements and maintains the affective and subservient bond between the disciples and their master beyond bodily co-presence. The practice of rabita has historically been aided by different technologies that serve to evoke visual imaginations, including hagiographical texts, miniature paintings, sketches of shrines, or photographs of Sufi masters.

So there is nothing new in using technologies for the purpose of rabita, except that social media affords the disciples to “interact” with their master in a virtual space shared with and accessible to other netizens of varying backgrounds. Consequently, most interactions that take place in Habib Luthfi’s Facebook page tend to reproduce forms of hierarchically-organized sociality of a Sufi congregation. Habib Luthfi’s followers tend to respond to new postings with deference rather than engaging with the actual message. They react instead by uttering Islamic formulae like “God is Great,” “Praise be to God,” “Glory be to God,” or by praying for Habib Luthfi. Some respond by asking Habib Luthfi about the meaning of the dream they experienced, requesting supplication or names for their newborn, or asking for advice and spiritual guidance. Others request for permission to recite litanies, be recognized as disciples, or apologize to Habib Luthfi for not being able to attend the monthly gathering, although from speaking to some of them I got the sense that they were not expecting any response. The absence of response certainly does not deter most of them from continuing to pose such comments, questions and requests. Used to facilitate rabiṭa, the content of the message itself becomes less important than the actual forms of connectivity (and visuality) that these media allow.

As the admin, Tsauri himself does not respond to any of the comments. Unlike other Muslim scholars who use social media to actively interact with their followers and critics, Tsauri only uses social media to simply relay Habib Luthfi’s ideas that are already articulated offline. When one senior disciple, who started to use Twitter to follow Habib Luthfi, was followed back by Habib Luthfi’s account, he sent an irritated private message to Tsauri requesting to be unfollowed, stating as his reason, the impropriety for a master to follow his disciple. Here, the act of following a Twitter account is perceived through the prism of Sufi ethical sociality. But the fact that the disciple requested to be unfollowed suggests a form of subservience that cannot be reduced to mere submission.

Ahmad Tsauri and his assistant standing in front of Habiblutfiyahya.net screenshot. (Photograph by Ismail Fajrie Alatas)

One repercussion of the reproduction of Sufi sociality in social media is the rising tendency of policing critical comments, not by the admin (who welcomes such engagements), but by other followers who position themselves as members of Habib Luthfi’s congregation. Netizens voicing critical comments are bullied by others, using expressions like “who do you think you are talking to?”, “please be more polite!”, “watch it, you are talking to a saint”, “God’s wrath upon those who criticize His friends,” and so on. Some respond to critical comments by telling the critics to go and visit Habib Luhtfi and clarify the matter with him. Others fault the admin for liberally posting Habib Luthfi’s statements, which in their view, generate misunderstandings. Note, however, that to police, bully, or express censuring expressions towards others in the actual physical presence of the Master would be deemed inappropriate, and yet they are considered acceptable in his “virtual presence,” which suggests that the social media facilitate but also transform Sufi sociality.

Sufi logics of interaction are inadvertently reproduced and reconfigured in Habib Luthfi’s social-media interface, despite the contrastive intention of its creator. Various (offline) institutional frameworks work to shape technologically-mediated interpretations and interactions, although mediatization also involves qualitative transformation of that which is being mediated. Beyond provoking excitements and concerns, social media allow for creative use and engagement by diverse actors that transcend their own commodified logics of production. Concurrently, they reconfigure established forms of Sufi sociality, complicating the notion of subservience to religious authority, which has been the hallmark or (to some) the bane of Sufism and Sufi orders.

References Cited

Pandolfo, S.

1997 Impasse of the Angels: Scenes from a Moroccan Space of Memory. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Cite as: Alatas, Ismail Fajrie. 2017 “Sufi Sociality in Social Media.” In “Piety, Celebrity, Sociality: A Forum on Islam and Social Media in Southeast Asia,” Martin Slama and Carla Jones, eds., American Ethnologist website, November 8. http://americanethnologist.org/features/collections/piety-celebrity-sociality/sufi-sociality-in-social-media