Carla Jones (University of Colorado Boulder) and Martin Slama (Institute for Social Anthropology at the Austrian Academy of Sciences)

Popular uses of smartphones at an Islamic college in Indonesia. (Photograph by Martin Slama)

How can anthropological analyses of religion illuminate rhetoric about the utopic and dystopic potential of social media? While religion and social media may seem like separate realms of social life, ethnographic analysis highlights their shared features and connections. Simultaneously promising or threatening disruptive social change through forms of discipleship, mobilization or celebrity, proponents and detractors alike traffic in the potential for social media and religion to overturn established hierarchies and deliver a more just future. Key events, such as the Arab Spring in 2010 and hashtag activism in the US following the death of Michael Brown in 2014, have become emblematic of the power of social media to organize resistant political movements. Yet when social media techniques are linked to pious religious identities, especially if the religion is Islam, these parallel features are often reframed as threatening. Much of the Orientalist rhetoric about of the use of social media by pious Muslims, such as the sensational provocations used by ISIS (Islamic State of Iraq and Syria), rely on similar assumptions about the dangerously enchanting mix of religion and social media. Such depictions assert a global emergency about Islamic social media as inherently contradictory, that pious Muslims employ a modern technology to serve a non-modern agenda.

This collection brings together original, concise ethnographies of Islamic social media uses from Indonesia and Malaysia to consider how Muslims themselves envision the effects of social media. As the world’s largest Muslim majority country, and the country with one of the largest number of Facebook users world-wide, Indonesia in particular makes for a compelling site in which to situate these questions. In the last year alone, Indonesia has seen two national political scandals arise on the basis of religious accusations circulated via social media. The former governor of Jakarta, Basuki Tjahaja Purnama (popularly known as Ahok), was voted out of office in March 2017, and then arrested, prosecuted and imprisoned for blasphemy in large part because of video footage of a 2016 campaign moment that circulated via social media. In May 2017, Rizieq Shihab, leader of the controversial Islamic organization Islamic Defenders Front (Front Pembela Islam) was charged on pornography accusations because of conversations and images exchanged with a woman who is not his wife, ostensibly captured from his WhatsApp account.

While these examples challenge the alarmist rhetoric depicting Islamic social media as a medium for circulating invocations to violence, they also ask for ethnographic analysis. The contributors to this collection ask how, while social media are intimate and ubiquitous in contemporary Southeast Asia, they are simultaneously sites of concern for their own users and creators. Debates about social media in Southeast Asia therefore index broader debates about the turn to public piety, Islamic reform movements, and the role of religion in other forms of social change. We find that tweets, Facebook groups, Instagram posts, YouTube sermons, and WhatsApp groups have an intertextual capacity that further amplify these connections and anxieties. Moreover, rather than take either theological orthodoxy or social media as forms of authority that can only be received and obeyed, this collection points to circulation, dialogue, and the possibility that public forms of communication can enter into personal life and circle back out to influence public culture.

Several themes emerge among these essays. Taken together, they illustrate the ways in which Southeast Asian Muslims find both religious piety and social media dialogically inform their sense of the world and their place in it. These effects are both personal and public, influencing personal life choices such as when to marry, and collective, such as institutional decisions about theology or policy. First, we find that Islamic social media have become sites for sorting out everyday dilemmas through religious community. Users, often younger people who have grown up in an internet era, demonstrate a strong desire to discuss personal topics and find online communities an appealing venue in which to do that. Second, Islamic social media have become alternative arenas for political expression, in part because they facilitate a lively, intense, often impolite discourse that is much harder to express face-to-face in Indonesian social life with its emphasis on hierarchy and propriety. While these expressions build on the ability to attract and maintain an audience, they also suggest that even though political discourse on social media globally seems to create opportunities for satire and humor, there is a bigger difference between online and offline communication in Indonesia than elsewhere. Additionally, social media have allowed for religious figures to ascend institutional hierarchies more rapidly or to circumvent them by finding new paths to Islamic authority. Finally, we find that social media have become venues for worries about truth itself. Accusations of pride and excess have become a common feature of the moral panics about social media in Southeast Asia, while defenses against accusations of self-promotion also emerge and circulate on social media. These critiques are frequently framed in religious rhetoric, adding to their moral tone.

Everyday worries can be answered through consulting religious authority or religious community, or both. Dayana Lengauer profiles the rise of a young female blogger in Bandung, Indonesia, whose account of her search for a pious husband, then of her engagement and marriage, attracted an online audience of young men and women who experienced similar worries. In a country where remaining unmarried is discouraged and where attempts to find the “right” partner often means navigating social pressures and religious authority, the risk of sharing intimate worries with an anonymous public was mitigated by stating that she hoped to structure a pious life.

None of these themes simply transfer unmediated from offline life to online life or vice versa. They are not one-to-one representations. Instead, they undergo transformations that suggest that while religion is a central feature of these debates, religion is neither the beginning nor the end of the conversation. This is most evident in the essays here which show inversions in the religious order of things. For example, how should one properly relate to a Sufi master or to an Islamic preacher online? As Ismail Fajrie Alatas and Martin Slama each demonstrate, Indonesian Muslims give different answers to these questions. Whereas moderators on online forums worry about how followers should properly address a Sufi master without subverting his authority, middle-aged female members of Islamic prayer groups have discovered that social media are an efficient way to directly contact male Islamic preachers, asking for guidance on private concerns at any hour of the day. If using social media is a growing but ambivalent practice for Sufi communities, it is essential for mainstream popular preachers, who find they cannot maintain a core audience if they ignore texted queries from followers.

The potential to proselytize via social media explains why digital venues have become essential for religious life in Islamic Southeast Asia. Bart Barendregt traces the popularity of Inteam, a Malaysian nasheed group (Islamic a cappella boy band), that uses a variety of social media platforms to amplify its musical distribution and to connect with its fans across the region. Inteam enjoys artistic and economic independence from major labels because they distribute music directly to fans online. Similarly, Wahyuddin Halim profiles the rise of Usman Pateha, a young Islamic preacher from a peripheral part of South Sulawesi. Through strategic use of Facebook, Usman has developed an audience of followers within As’adiyah, an influential but nonetheless regional Islamic organization in eastern Indonesia, to now national stardom, with two national television shows. These examples underscore a financial feature to the institutional and theological intersections of religion and social media. Social media have also become a key site for new religious proselytization, such as One Day One Juz, a movement that encourages members to read one chapter (juz) of the Qur’an every day and connects them via WhatsApp groups in which users are obliged to report their Qur’an reading activities. As Eva Nisa describes, the leaders of One Day One Juz also share particular religious messages on social media – often in response to contemporary social and political developments in Indonesia. As Daromir Rudnyckyj demonstrates, Malaysian financiers are aiming at other connections by attempting to position Malaysia as global hub for Islamic banking, through merging theological expertise on finance with their admiration for Silicon Valley’s celebrated social media companies. The result is a hybrid form of venture capitalism that generates its own tensions.

Indonesian smartphone apps to guide a pious life. (Photograph by Martin Slama)

These tensions are varied, but coalesce around ambivalence about the reliability of new forms of success that social media either facilitate or document. They can be about the nature of celebrity itself, but when articulated in religious terms can take on an explicitly ethical dimension. Social media are fundamentally forms of display, which entail pleasures and risks that are not equally distributed. Fatimah Husein points to a concomitant “revival” along with the revival of Islamic piety in Indonesia, the revival of riya’, i.e. boasting about pious deeds which is strongly discouraged by Islamic orthodoxy. Reading the Qur’an in social media groups or participating in Islamic charities that are organized online therefore entail a theological risk of display to other worshippers, and in the process submitting to the admiration of other humans rather than to the divine. The stakes of committing riya’ can be sufficiently high that some of Husein’s interlocutors voluntarily withdrew from religious social media communities. Carla Jones further suggests that these stakes vary intersectionally, with a particular vulnerability for women. Tracing the debate about whether posting selfies online is sinful or not, Jones argues that “social media cannot be separated from their spectacularity.” In spite of these anxieties, Husein and Nisa both document the ease with which members of these groups enter and leave, bearing little evidence of the hypnotic devotion that outsiders might imagine religious social media demands.

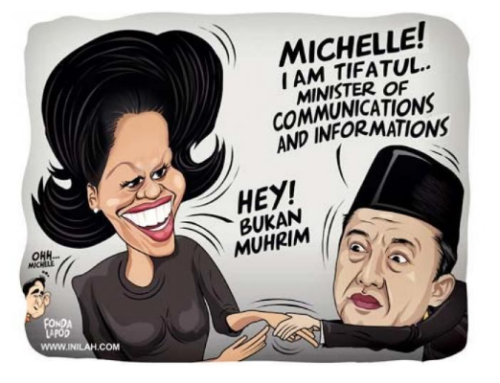

Nonetheless, these anxieties can take on a collective quality, extending personal worries into the public sphere. James Hoesterey describes how online political culture in Indonesia is saturated with “vociferous dialogue and debate, ridicule and satire.” Memes, cartoons and manipulated pictures have become part of public discourse and spur debates about the “fake” or “authentic” piety of Muslim politicians. Further, as John Postill and Leonard Chrysostomos Epafras demonstrate, debates about what constitutes true Islam can go viral, especially when, for example a female Muslim politician criticizes an Islamist group on Twitter. To date, however, the most conspicuous example of the nexus among Islam, politics and social media are the massive demonstrations in Jakarta in late 2016 against Ahok, the then governor of Jakarta. His status as an Indonesian Chinese and a Christian informed the circulation of a manipulated video posted on YouTube of a scene from his reelection campaign, in which he appeared to be interpreting a Qur’anic verse about political leadership in a controversial way, leading to a subsequent blasphemy charge. Saskia Schäfer analyses the complexities of this movement, which started online and shifted into to street demonstrations which were themselves organized through social media by a coalition of the governor’s rivals, including leaders of Islamist groups. Importantly, she identifies how economic policies mobilized marginalized Jakartans, even as protest organizers insisted on the respectability, humility and hygiene of demonstrators. Pointing at how grievances, piety and anger can intersect, she unravels “what turns YouTube clicks into marching feet” in ways that differ from simple accounts about Indonesia turning towards a more Islamist political culture.

These varied examples show how fundamental concerns about the role of social media in creating sincerity, truth, and justice overlap intimately with the ethical underpinnings of religiosity. These fascinations now feel almost futuristic in their prescient match with similar impulses in contemporary elsewheres. The fact that Southeast Asian Muslims address these shared desires and worries in ways that are by turns vociferous and humorous, intense and effortless, may also suggest hope about the power of creativity in uncertain and sometimes exhausting conditions.

Acknowledgements

Many of the essays in this collection were initially presented at the workshop “Social Media and Islamic Practice in Southeast Asia,” which took place in April 2016, in Vienna, Austria. The workshop was an initiative of the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) project “Islamic (Inter)Faces of the Internet: Emerging Socialities and Forms of Piety in Indonesia,” which is directed by Martin Slama at the Institute for Social Anthropology, Austrian Academy of Sciences.

Cite as: Jones, Carla and Martin Slama. 2017 “Introduction: Piety, Celebrity, Sociality.” In “Piety, Celebrity, Sociality: A Forum on Islam and Social Media in Southeast Asia,” Martin Slama and Carla Jones, eds., American Ethnologist website, November 8. http://americanethnologist.org/features/collections/piety-celebrity-sociality/introduction