One November night in 2016, Fatih Altaylı, a famous news anchor in Turkey, hosted three men on his live television program to discuss the country’s agricultural future. One was Selim Çetiner, a horticulture professor at Sabancı University in Istanbul. The two others were back-to-the-lander urbanites engaged in what is commonly known as ecological cultivation, a type of farming done without synthetic chemicals. They were Durukan Dudu, the founder of Anatolian Grasslands, an accredited hub of the Savory Institute in Turkey focusing on holistic management, and Mustafa Alper Ülgen, the founder of a local chapter of Slow Food.

I came to know about this event through the posts of friends and acquaintances that appeared on my Facebook newsfeed right before it aired. Concerned as they were with the state of agriculture in Turkey, many of the people offering comments online expressed excitement at the opportunity of being on national television. “There are people who do good deeds, whose concerns are land, seed, and the Earth. (…) The television shall be useful for once,” one commenter said, referring to Dudu and Ülgen and the larger ecological community they represented. Another noted the irony of appearing on Altaylı’s program, for he was infamous for his sporadic impertinence and political opportunism. Yet this could be an opportunity to “make noise,” he continued, that is, render issues visible to wider publics.

Since the early 2000s, proponents of ecological production and consumption in Turkey have been raising awareness about the various negative effects of conventional agriculture, including on ecological systems. Arguing against the increasing industrialization of the agri-food sectors, they have been advocating for a switch towards agroecological methods and away from the heavy use of artificial fertilizers and biocides, which have made farmers highly dependent on capital and transnational corporations. While their advocacy work managed to reach public audiences from time to time, as when the anti-GM platform gained traction during the 2004 campaign, its overall impact has remained rather limited. The excitement articulated on my Facebook feed thus raised concerns over visibility: Would having the opportunity to champion the cause on national television serve to convince wider audiences?

The show proceeded with an air of an unacknowledged contest. On one side, the professor defended conventional agriculture by claiming, as many do, that it would be impossible to feed the world’s population without it. As a proponent of genetically modified crops, he touted new technological innovations that would produce more food without harming the environment, a process he called sustainable intensification. This, he argued, would enable a delicate balancing act that could simultaneously increase productivity and keep costs low without harming the environment. On the other side, Dudu and Ülgen questioned the viability of conventional agriculture in the first place, referring, among other things, to the failed promise that the Green Revolution would feed the world, the high energy input required for technological fixes, and the problem of world hunger being tied to distribution and access, rather than to production.

Dudu cited a specific figure, which the professor also confirmed: 60% of the world’s arable land is used to grow feed for animal husbandry, and not directly food for humans. This fact poses a challenge to the conventional notion of increased food production through industrialized agriculture. Meanwhile, the quality of soil on arable land deteriorates even as grasslands lay unused. Rather than resorting to a makeshift version of sustainability, Dudu explained that it was possible to repair soil and increase productivity without relying on industrial inputs, through a process called regenerative agriculture. Translated into Turkish as reparative agriculture (onarıcı tarım), this type of farming restores minerals in soil, which is often depleted of its nutrients and organic matter due to decades of being subjected to conventional farming methods. Dudu mentioned twice that regenerative agriculture had recently been featured in The New York Times. Carefully unfolding their argument, his colleague Ülgen then drew from another resource to argue for the possibility of increased yield via ecological farming. He had studied recent reports by the UN and WHO that described how potato production in Bolivia had increased from 4 to 15 tons per hectare. In Cuba, vegetable production in urban gardens had redoubled. In famine-stricken Ethiopia, sweet potato production had expanded, and so did corn yield in Kenya—and all through ecological methods.

Mulching is a common method used in ecological cultivation primarily to prevent weeds and conserve soil moisture. Photo by author.

The conversation lasted for two and a half hours, with peaks of argumentation and fleeting moments of agreement between the two sides. Meanwhile, a parallel discussion ensued in the online world. On the one hand, followers of Dudu and Ülgen commented on Facebook as they watched the show, deeming the professor’s support of conventional agriculture as horrifying. They repeated their concern as to whether the message of the significance of ecological farming would reach its audience. On the other, after the show was uploaded to YouTube, people from the public posted comments from a different perspective. One wrote, “Why do you put these romantic and irrational people on TV, these people who believe that the whole world could be full up from food grown in the garden? (…) It’s time to not let these Cuba-lover people who lost their minds appear on TV and perplex the public.” And he continued, “My dear professor (hocam) is speaking scientifically and reasonably, as expected from scientific ethics. These guys (herifler)1 you have out against this man are only conspiracy theorists.”

This commentator’s position, which could be a minority one, still confirms the fear articulated by the pro-ecological cultivation community on Facebook that visibility on national television does not equate to the successful propagation of the ecological cause. In fact, I would argue that while Ülgen and Dudu may have convinced some viewers, their advocacy ultimately ended in failure, as indicated by the negative comment that they received online. This failure, as I understand it, is located in the failure of their citation of presumably reliable data sources to have a meaningful impact on the listeners. But rather than understand this as mere failure, we may also think about how information, statistics, and data that circulate in public discourse are never simply received as such. Instead, they are filtered through what one already knows, how one cognizes, and how one is embedded in structures of sentiment, which often signal how one responds to specific kinds of authority. In this instance, anti-communist sentiment, a curious distinction between scientific ethics and romantic irrationality, and possibly distrust of foreign sources and institutions seem to have worked together, disallowing this person from even considering Ülgen and Dudu’s claims in their own terms.

In referencing reports from the UN and WHO, Ülgen mentioned several countries, of which Cuba was only one example of success. Otherwise, nothing in what Ülgen and Dudu said evoked communism. Despite this, the commentator extrapolated that they were “Cuba-lovers,” which led him to dismiss all arguments in favor of ecological farming.

That Çetiner, the third speaker, was a professor at a prestigious university in Istanbul and therefore a scientific “expert” may have added to Ülgen and Dudu being dismissed as non-experts. Here I am reminded of the firm adherence to a vision of expertise within Turkey that remains exclusive to academics. Even the host of the show made this view explicit at the very beginning. “Let’s start scientifically,” he said to set off the conversation, “therefore we start with hocam.” Meaning “my teacher,” hocam is a form of address used towards teachers and professors, which always implies reverence. Like Altaylı, the Youtube commentator uses this address to show respect to the professor. He also assumes Çetiner’s objectivity for being a scientist, therefore revealing an understanding of science as disinterested: the professor-scientist could simply not be driven by political sentiment, unlike the possibly left-leaning, Cuba-mentioning “conspiracy theorists.”

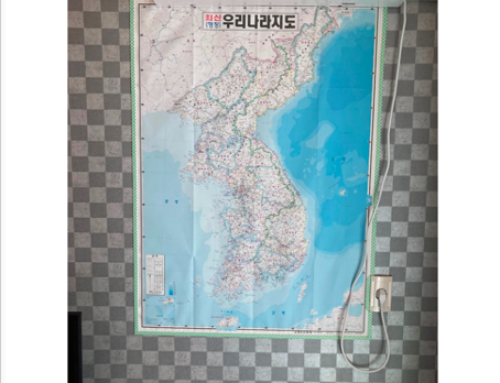

Trainings on agroecological methods teach current and aspiring farmers to identify the state of soil health and potential intervention techniques. Photo by author.

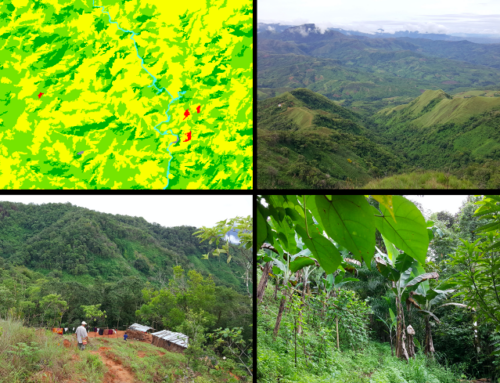

Unlike Çetiner, Dudu and Ülgen had no credentials that gave them expert authority in ways easily recognizable to the wider public, even though they had gone through various trainings since they started practicing ecological farming. Permaculture, the most known agroecological method in Turkey, is often taught in a 72-hour training where participants get exposed to a curriculum developed by Bill Mollison and David Holmgren, the original designers of the method. Internships and volunteer opportunities in permaculture farms as well as specialized courses on topics such as rainwater harvesting or compost methods further allow a practitioner to develop something akin to a CV. At the same time, on-site practice often involves autodidactic methods, including reading and watching educational materials, applying new knowledge in the field, and learning from mistakes. Holistic management has similar ways of establishing expert authority and institutes that provide accreditation. However, none of these is recognizable to the public. Altaylı, too, failed to acknowledge this lay form of learning and sharing knowledge as expertise. He expressed astonishment at Dudu who presented himself as a shepherd. “You graduated from Galatasaray University, but you are a shepherd,” he interrogated. In juxtaposing Dudu’s educational background with his chosen occupation with such curiosity, the host made clear that in his mind the two did not align. In addressing Dudu, the youngest of the three participants, Altaylı also switched to the informal you, which may be read as diminutive.

While the show demonstrated a tension between different understandings of expertise, the unquestioned credibility Çetiner garnered may have also been related to how differently the speakers presented themselves in public. The professor appeared on TV in business attire wearing a navy suit and tie. Next to him, Dudu provided a stark contrast, with his simple blue T-shirt, unkempt beard, and ponytail. Ülgen was clean-shaven but had also dressed casually. He wore a charcoal-colored work shirt and a light gray cap, and his jeans were visible to the viewers due to the angle of the camera.

In addition to using agroecological methods for cultivation, farmers of ecological food often use and revitalize heirloom seeds. This photo features four chickpea varieties. Photo by author.

Despite lacking the audience’s appreciation as trustworthy experts, Dudu and Ülgen specifically emphasized that they were citing reports by the UN and WHO, which are internationally recognized expert institutions. None of these seem to have registered as references to expert opinion for the YouTube commentator. To recognize these sources as such, he would first have needed to acknowledge that scientific discourse itself may be internally divided—that different forms of evidence may be gathered in different ways to make varying claims about the world. There may, however, be another sentiment at play here as well: a distrust of international organizations fueled by nationalist sentiment. Many political, social, and economic problems in Turkey are explained within public discourse as stemming from “foreign powers” and their malicious intervention into Turkish affairs. Therefore, a general skepticism toward western sources and institutions, including The New York Times, might make Dudu and Ülgen authorities to be avoided precisely because of the citations they used, and might even go so far as to signal that they are in cahoots with these “foreign powers,” thus rendering their speech as conspiratorial. In the end, the data shared by Ülgen and Dudu failed to register for the commentator as well as for the broader audience. Due to dominant understandings of expertise and structures of sentiment in Turkey, it was perhaps bound for failure from the start.

Notes

[1] This word carries a derogatory connotation to refer to a man who cannot be trusted.

Bürge Abiral is a President’s Postdoctoral Scholar in the Department of Anthropology at Ohio State University. She received her PhD from Johns Hopkins University in 2023 and her MA in Cultural Studies from Sabancı University in 2015. Her dissertation, titled At the Threshold of Possibility: Cultivating Ecological Relationality in Neoliberal Turkey, explores the contemporary back-to-land movement in Turkey in the context of the emergence of alternative food networks and the rise of sustainable living among urbanites.

Cite As: Abiral, Bürge. 2023. “Sieving Data” In “data/Big Data in the field” edited by Naveeda Khan, American Ethnologist website, December 22 2023, [https://americanethnologist.org/data-big-data-in-the-field/sieving-data/]