In April 2018, the whole country was celebrating the historic meeting of the summit of the two Koreas. I remember the anxious atmosphere in the house of Youngdo,1 a North Korean migrant woman in her late 30s. She had been living in South Korea for the past six years, after leaving her hometown for China in the midst of the North Korean famine in the late 1990s, dubbed the Arduous March. The news on the living room TV was repeatedly showing the scene of South Korean President Mon Jae-in shaking hands with the Supreme Leader of North Korea, Kim Jung-un. Youngdo turned away from the TV. “It’s like being a hostage in the South,” she said in a low murmur. “I don’t know when we will be served as a gift to the North.” She then turned her eyes toward the table, telling me to eat more of the Chinese dumplings she had prepared for us. The summit kept playing in the background.

The unification of the two Koreas is often treated as a peace reckoning, exemplified by the famous Korean song “Our Wish.” The plight of separated families (isan’gajok) has long provided a rationale for both states to reunify, thereby putting an end to the tragedies of the Korean War (1950-1953). However, this prevalent presumption that unification equals peace, bolstered by images of separated families being united, was challenged as I became attuned to women’s words about their families who were dispersed across North Korea, South Korea, and China.

North Korean migrant women living in South Korea, often referred to as defectors and refugees, are commonly depicted as victims of the authoritarian North Korean regime and of human trafficking. Among these diverse forms of victimhood, the ways that the Partition of Korea mark their everyday life generally goes unrecognized. During my long-term fieldwork with North Korean migrant women in a southern province in South Korea, their gestures and words kept reminding me that the Korean War was still present. The fact that the war remains unending goes without saying, but seeing it in small flashes felt odd. Youngdo secretly revealed to me a dark side of the “new era of peace” that President Moon unleashed upon his signing of the Panmunjom Declaration during the summit. Subsequently in August, the 21st reunion of separated families was held. None of my interlocutors applied for the reunion lottery, nor did I hear anything about their intentions to apply.

In this essay, I show how the state’s collection of data on the North Korean population in South Korea, under the legal category of Bukhan Italjumin (literally translated into Residents who Defected from North Korea), occludes their experiences of familial separation. According to the Act regarding Separated Families, North Korean migrants and their kin in the North fall under the category of separated families,2 yet they are not recognized as such in its juridical processes or in public discourse. What if we attended to the myriad ways by which migrant women weave absent family back into their everyday lives?

The Settlement Surveys

The Settlement Survey of Bukhan Italjumin (hereinafter referred to as the “Survey”) is administered annually by the Korea Hana Foundation (KHF; North Korean Refugees Foundation), which was established in 2010 by the Ministry of Unification under the amended Protection and Settlement Support Act, originally implemented in 1997. Under Article 4-3 of the amended Act of 2014, the Minister of Unification is mandated to use the Survey results to formulate a triennial master plan for the protection of—and settlement support for—North Koreans who are deemed eligible. The purpose of the Survey not only lies in collecting data on the general life of the North Korean population in South Korea, but also in implementing welfare policies to “protect” them. My consideration of the Survey attends to how North Korean migrants’ experiences of dispersed family get eclipsed in the very data collection and policy-making processes that have been set up to illuminate them.

The Survey focuses on two analytics: settlement status and social integration. Data on the family is collected by the latter, which counts the “family” (gajok) as equivalent to members of the household (gagu). Within the legally defined boundary of the household, the family of North Korean migrants is primarily considered to be those with whom they live, together and under the same roof. Therefore, families who do not share the same household fall outside the parameters of the Survey.

An exception can be found in one of the response options to a question about reasons for “life dissatisfaction,” which can be found in the settlement status survey under the category of Levels of Life Satisfaction. The option states, “living away from my family.” The latest 2022 data shows this to be the most popular response to the question (selected by 29% of respondents), followed by “intense competition” (around 20%) and “discrimination” (around 17%). The third master plan for the protection and settlement support for North Koreans (2021-2023) mentions these data, right below a line emphasizing the increasing percentage of the respondents (from 76.5% in 2021 to 77.4% in 2022) who answered questions related to life satisfaction.

Under the plan’s vision of “realizing a warm society in which Bukhan Italjumin become [our] neighbors,” proposed policies appear to be oriented towards enhancing economic self-reliance and inclusive society, which in turn seems to reflect the other two reasons selected for life dissatisfaction. Even though “living away from my family” continues to be selected so frequently, it is assumed that this will be rectified by the Committee for the Five northern Korean Provinces’ family-matching program between North Korean migrants and those displaced by the Korean War—the so called “residents in the unreturned cities and counties of the five northern provinces” (ibuk 5domin)—who comprise “separated families” in the South. Because any form of contact with persons in North Korea is deemed an act of national treason by the National Security Act, North Korean migrants’ sentiments related to the dissatisfaction of “living away from my family” must be coped with privately and clandestinely.

One of my interlocutors who refused to participate in the Survey astutely asked “[f]or whom the data is produced.” North Korean migrants’ experiences of kinship, separated into the North and the South and dispersed across the third country, is not only occluded in the data but is also selectively silenced in the public sphere. Below I reflect on my tentative efforts at collecting family genealogies and consider the curiously generative ways in which my interlocutors refuse this occlusion.

Surnames

In April 2022, as I was having late lunch with Hyesuk in the living room of her house, Hyesuk took out a pamphlet she received from the foster facility that cares for her son, Min. When she was in China, Hyesuk had Min with her Chinese husband, who had passed away when Min was six months old. Hyesuk brought Min on her journey to South Korea when Min was almost a year old. Min is now thirteen. Hyesuk opened the pamphlet to a page where a poem written by Min had been photographed. On the top of the page next to the title of his poem, Winter, Min’s full name appeared, written out in his own handwriting. I noticed his surname, “Kim,” was different from his mother’s surname, “Park.” I wondered about this, because North Korean migrant women typically register their children born in China to the Family Relations Register with their own Korean surnames, rather than with the Chinese surnames of their fathers. I asked Hyesuk if Min’s surname was “Kim.” “I gave Min his older sister’s surname,” Hyesuk replied.

Min’s older sister is Hyesuk’s daughter from her first marriage to a North Korean man. On many nights at Hyesuk’s apartment, I was told about how her first husband mistreated her, and how this had eventually made her leave everything behind in the North. She mused that it would not be surprising if she were to die today or tomorrow, as her illness had long been festering. Hyesuk filed for divorce from her North Korean husband as soon as she was relocated to her current apartment, after the mandatory three-month resettlement program at Hanawon. It was to prevent a situation in which she would have to live with him as a married couple if he had come to the South. Based on the stories of betrayal and disappointment through which I slowly had come to learn about Hyesuk’s kinship relations, which were materialized in her divorcée status as well as the absence of her daughter on her Family Relation Certificate, I had a hard time understanding. Why had Hyesuk given her son his sister’s surname?

In Korean kinship, women are not supposed to be in a position to pass their surnames to children, and they were legally prohibited to do so until the 2008 abolition of the “head of family” system (hojuje) in South Korea. From this perspective, Hyesuk giving her son the surname of his sister may seem like an act that transgressed patriarchal kinship norms. Following this kinship logic, her son’s surname may signal his genealogical ties not only to his sister, but also to her father, Hyesuk’s ex-husband. Nonetheless, it did not seem like she was seeking to give a voice to the patrilineal genealogical norms. I asked Hyesuk carefully why she did not give Min her own surname. Hyesuk responded: “If something good happens, Min can see his sister. Or perhaps his sister might come down to the South before then. If I die, for Min to find his sister, their surnames should be the same.” To my curiosity of what she meant by “something good,” she replied, “When unification comes.”

Genealogical Connections

A few months later, I was at Hyesuk’s house, drawing her kinship chart in my notebook. She allowed me to draw it with her, yet was complaining that the chart was of no use. She looked down at the chart-in-the-making that was becoming hurly-burly with details. The square with Min’s name appeared next to the circle of her daughter. Pointing down at the square, Hyesuk said, “Min is a seed scattered in an empty plain.”

Her expression immediately brought me back to the moment when she told me about giving her son the same surname as her daughter. Perhaps she meant that she herself was an empty plain? The density of her family had turned into a profound absence. Yet, bringing Min with her to South Korea and giving him that surname suggested a kind of planting that might extend out to his sister, or perhaps draw his sister to him. Hyesuk’s separation from her dispersed family is marked by the Partition and domestic abuse. Hyesuk’s letting her son and daughter be called by the same surname, like many other siblings, might be the everyday work that allows life to be knitted together (Das 2020), even though the genealogical connections between her children cannot be acknowledged elsewhere but by her, at least not until the war ends.

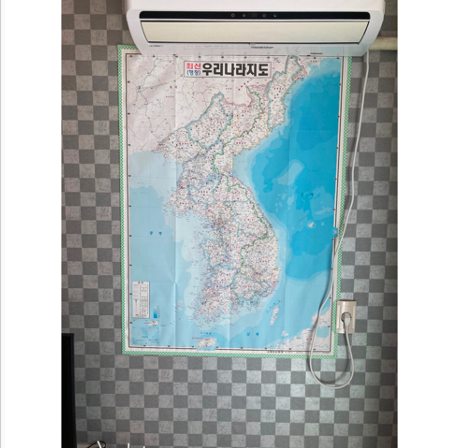

This map of Korea hung on Hyesuk’s living room wall. During our conversations, we often referred to places on this map, including her hometown. Our distance from them was not far. Photo by the author, with permission from the interlocutor.

Notes

[1] All interlocutors’ names in this essay are pseudonyms to protect their anonymity.

[2] See Yoon Hee Kim (2022) for more on the arbitrary assignment of the category of separated families. This category has life-determining consequences (Kwon 2020).

Acknowledgments

I thank Youngdo unni, Hyesuk unni, and my interlocutors who continue to teach me about inhabiting life with others, especially with kin. I appreciate Professor Naveeda Khan and the AES Editorial Team for their generous feedback on earlier drafts of this piece. Professors Clara Han and Veena Das have been key in inspiring me to be attentive to women’s voices in scenes of kinship.

References

Das, Veena. 2020. Textures of the Ordinary: Doing Anthropology after Wittgenstein. New York: Fordham University Press.

Kim, Yoonhee. 2022. “How the ‘Divided Family’ is reproduced? The Third Generation Family History of Grandma Cho from ‘Unrecovered Area.’” The Journal of Asiatic Studies, 65(3): 41-89.

Korea Hana Foundation (North Korean Refugees Foundation). 2017, 2018, 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022. Settlement Survey of North Korean Refugees in South Korea. http://dongposarang.com/home/eng/resources/research/index.do?act=detail&idx=6&searchValue1=D&searchKeyword=&menuPos=20.

Kwon, Heonik. 2020. After the Korean War: An Intimate History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ministry of Unification. February 2022, 2023. 2022, 2023 Settlement Support for North Korean DefectorsImplementation Plan. Retrieved from National Strategic Information Portal https://nsp.nanet.go.kr

Sojung Kim is a PhD candidate in Anthropology at Johns Hopkins University. Her research investigates the intersection of politics and kinship, by tracing how disordered politics come to be entangled in disorders of kinship in the context of North Korean migrant women’s transnational kinship across North and South Korea, and China. She received her MA in Anthropology and Sociology of Development from the Graduate Institute, Geneva, and her BA in Philosophy from Yonsei University. Before joining Johns Hopkins, she worked with a feminist activism group in Daegu, South Korea.

Cite As: Kim, Sojung. 2023. “Data Collection of Kinship” In “data/Big Data in the field” edited by Naveeda Khan, American Ethnologist website, December 22 2023, [https://americanethnologist.org/data-big-data-in-the-field/data-collection-of-kinship/]