Algo-r-(h)-i-(y)-thms, 2018. Installation view at ON AIR, Tomás Saraceno’s solo exhibition at Palais de Tokyo, Paris, 2018. Photo by Alina Grubnyak on Unsplash. Collection cover image by Joshua Sortino on Unsplash.

Before there was Big Data, there were data, numbers, and facts compiled to be examined and considered for decision-making. With its premise that data accumulates at such rates and quantities that only machine prowess allows us to have a perspective on it, Big Data is edging out of consideration this more deliberate and necessarily smaller-scale mode of training a curious eye on the world by means of observation, experimentation, and/or enumeration (Lepore 2023). The short pieces gathered here by anthropologists at various stages of conducting fieldwork take up for consideration what might constitute data with a small “d”. In so doing, they ask what it means to look at the world with a more modest eye and how this modesty is to be transvalued. I would further argue that these essays, written in the aftermath of Big Data, are influenced by Big Data values (velocity, volume, value, variety, veracity), if not methods, and moderate these values in turn.

Data Collection: The achievements of these thoughtful contributions are many. Prompted by the question posed to them about where and how they encounter data in their fieldwork, we see these ethnographers’ slow realization that something ordinary—right under their noses, in fact—not only operates as data, but also gathers data to itself. In “Barcodes as Little Tools of Medical Knowledge,” Zeynel Gül shows how it dawned on him that the barcodes on medical files in an Occupational Diseases Unit in Turkey that identify patients also effectively disperse the patient’s body across different sites and then reassembles it for the purposes of diagnosis. While barcodes still have the look of data in our contemporary, technologized sense, in “Power ≠ Knowledge: Govenmentality in North Indian Pilgrimage Ledgers,” Kunal Joshi shows how centuries-old genealogical records— manually inscribed on paper and copied over to new ledgers when the paper quality deteriorates, and used for Hindu ritual purposes—are formatted such that they are best approached through informatics, at the intersections of people, information, and technological systems, rather than textual interpretation.

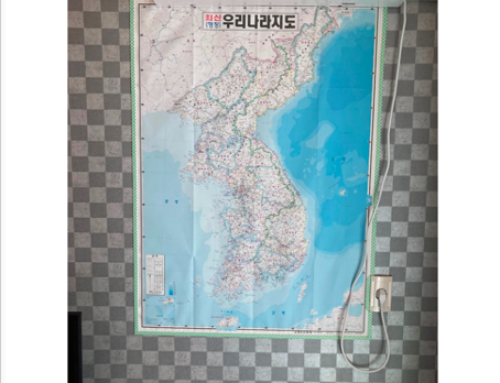

While Gul and Joshi show us how data collection and formatting may be woven into ordinary objects and religious artifacts, Youjoung Kim’s “Collecting Jeju 4·3 (Sasam) Records from the US Military Archive” shows that small tools of knowledge, such as a chronology of events or name index, can be integral to navigating data. Her work further demonstrates how much iterative labor and ingenuity enters into drawing out meaningful data from a glut of data, in her case the declassified records of U.S. military occupation of South Korea. Continuing Y. Kim’s line of making data out of existing data, we have Sumin Myung’s “Inheriting Data in Long-Term Ecological Studies,” in which he explores a scientist’s conundrum of inheriting a field site of a patch of trees in South Korea that contains markings of previous study whose research findings are missing. The detective work necessary to recover some of these findings suggest that despite the novelty of our equipment and methods and the types of data we seek, our questions are overlaid on prior research and our inquiries are always in medias res.

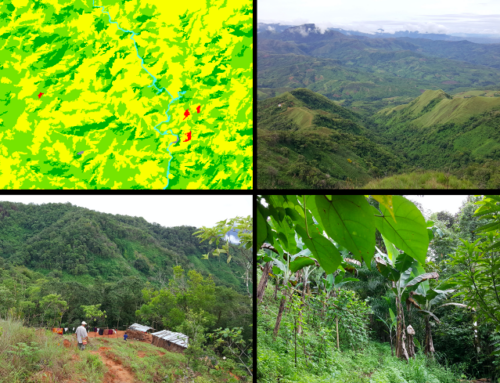

Data Mediation: Then there is the ethnographer encountering surprising data references in the discursive terrain of their fieldwork. This may take the form of a sudden eruption of numbers from elsewhere through a passing reference, such as in the case of Marios Falaris who, in their essay titled “Unemployment Uncertainties: Work, Status, and Measurement Imprecision,” writes how competing labor surveys and employment indices structure Kashmiri men’s expressed contradiction of feeling unemployed even while having work. In contrast, Bürge Abiral, in “Sieving Data,” describes how a statistical reference grounded in an international report cited in a nationally televised discussion in Turkey fails to resonate with its audience because of its association with foreignness. These two examples remind us that there are many mediating factors between data collection and its reception, raising the question of why certain datum is taken up with alacrity and another not, a question also explored by Tushar Mehta. In his post “Taxing Data,” Mehta shows the degree to which a new tax code in India relies on the digital to not only make possible widespread capture of tax related information but also to signal the state’s commitment to transparency and incorruptibility to encourage the code’s widespread uptake. By the same token, Perry Maddox’s “Data, Distance, and the Making of Forest Carbon,” reveals how value neutrality is assigned to what he calls “perspectives from the air” via satellite or drones for well-meaning research objectives of studying forests in Panama. These studies aim to produce more accurate accounts of the extent to which Panama is a carbon sink rather than emitter. However, they are punctured by the counter charge that these modes are invasive, not unlike surveillance.

Data Re-creation: Like Falaris, Sojung Kim in “Data Collection and Dispersed Kinship,” focuses on surveys to show how occlusions are structured into them such that the numbers to which they give rise do not fully or adequately represent realities like those lived by North Korean migrant women in South Korea with children left behind. Her post suggests why statistical citations, as in Abiral’s case, may be met with suspicion by those excluded from knowledge production, even as they find creative (albeit tiny) workarounds to secret in desires for the future into these surveys. Benita Menezes’s “Multifarious Lands, Conflicting Claims” similarly shows how agriculturalists in India faced with imminent displacement by megaprojects try to keep their futures open within the crosshatching of numerous laws and judgments that seek to exclude them from that future. Finally, Talia Katz’s “Between Fantasy and the Difficulty of Reality in Israeli Psychiatry” explores the poetics of data inscriptions—in her case, in notes maintained by an Israeli psychiatrist on her patients, survivors of the Holocaust, which enable a different reading and re-diagnosis of the patients in the present. Katz asks: what is it about the inscription of details that enables this re-reading in the present?

Such then are the rich offerings put forward in this special collection about data in the field. Readers may wonder why I even raised the issue of Big Data at the outset, given that all the contributions seem to disconnected from the phenomenon and committed to the idea that modesty yields singular—rather than representative—perspectives on social realities in our present (see Das 2015). I would argue that Big Data exists in these posts not in its disavowal but in the insistence that modesty has its own value, that singularity yields not just singular/unique lives, but also as Das argues, “figures of thought,” engatherings of ideas, feelings, and concepts. In other words, the barcode, the pilgrimage ledger, the US military archives, the patch of trees, the state of work, the agroecological future, the tax code, carbon emissions, North Korean migrant women, agriculturalists in India, and survivors of the Holocaust, are figures of thought that can exist both in their singularity within ethnography, and as engatherings within Big Data, if indeed the latter can manage carrying a variety of complex formations across its volume without allowing them to fall into caricature. While velocity, or the quickness with which data analysis can be delivered, is greatly valued within the industry of Big Data, what these posts suggest is that velocity is not only vectored towards the future but also has reiteration, repetition, retries, and re-readings built into it. Delay and return need to be intrinsic to our theorization of Big Data, not considered its excess or other. Finally, these contributions suggest that the veracity of a claim, even one wagered as fact, can only be secured by contestation and risking failure, and never once and for all. Big Data must enter into contestation with every other form of data before we can decide in its favor (or not).

Acknowledgements

This collection grows out of the Andrew Mellon Foundation funded Sawyer Seminar on “Precision and Uncertainty in the World of Data” hosted by Johns Hopkins University (2019-2022). It is dedicated to Dr. Veena Das, teacher, mentor and friend, on the occasion of her retirement from Johns Hopkins University.

References

Lepore, Jill. 2023. “The Data Delusion.” In The New Yorker Mar 27 https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2023/04/03/the-data-delusion

Das, Veena. 2015. “What Does Ordinary Ethics Look Like?” In Four Lectures on Ethics. Ed. Michael Lambek. Chicago: Hau Books.

Naveeda Khan is Professor and Chair of the Department of Anthropology at Johns Hopkins University. She is the author of In Quest of a Shared Planet: Negotiating Climate from the Global South (2023), River Life and the Upspring of Nature (2023) and Muslim Becoming: Aspiration and Skepticism in Pakistan (2012).

Cite As: Khan, Naveeda. 2023. “Introduction to ‘data/Big Data in the field'” In “data/Big Data in the field” edited by Naveeda Khan, American Ethnologist website, December 22 2023, [https://americanethnologist.org/data-big-data-in-the-field/data-big-data-in-the-field-n]