The National Archives at College Park, Maryland, also known as NARA II, houses a rich repository of materials that encompass US military reports pertaining to World War II prisoners of war and intelligence reports spanning the globe. Within NARA II’s permanent collection, approximately 1-3% of federal records are meticulously preserved, totaling 13.28 billion pages of textual records; 10 million maps, charts, architectural and engineering drawings; 44.4 million still photographs, digital images, filmstrips, and graphics, along with 40 million aerial photographs; 563,000 reels of motion picture film; 992,000 video and sound recordings; and a staggering 1,323 terabytes of electronic data (National Archives, 2021).

Textual Research Room at NARA II. Photo by Youjoung (Yuna) Kim.

Over an intensive three-month research endeavor at NARA II in 2022, our team, representing the Jeju 4·3 Peace Foundation and composed of researchers from South Korea alongside myself, delved into this vast archive. The work involved the collection of an array of records, including documents, still images, maps, and aerial photographs, all of which were pertinent to the violence of Jeju 4·3 (Sasam), spanning from 1947 and 1954. Our primary goal was to shed light on the extent of US involvement in the tumultuous events of Jeju 4·3. Throughout this research, I realized that seemingly mundane tools of knowledge—like lists of events, photo captions, and tables—proved to be invaluable in navigating the intricate web of record discrepancies and organizing our data.

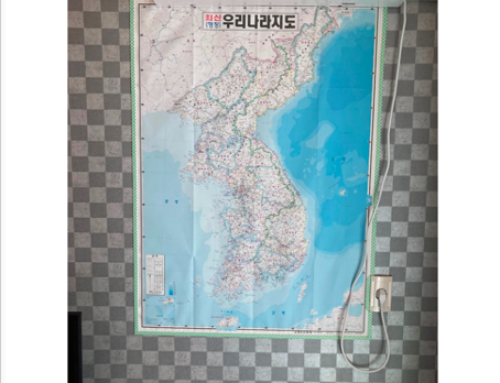

The violence in Jeju began with political unrest, exacerbated by the post-World War II division of Korea. This division occurred following Japan’s surrender, and the subsequent proposal by the US to establish the 38th parallel as the demarcation line for the Korean peninsula. Within this context, the islanders harbored aspirations of joining their mainland counterparts in forging a unified Korean nation. This fervent pursuit culminated in an uprising on April 3, 1948, marking a pivotal moment in the island’s history. Notably, Jeju residents abstained from participating in the May 10, 1948 national election, which aimed to create a separate congress for the South. In a stark turn of events, officials of the US military government in Korea branded the islanders as communist sympathizers, leading to the ruthless suppression of their dissent. The government’s repressive actions continued, evolving into a protracted counterinsurgency conflict following the formation of the first South Korean government in August 1948. Tragically, the violence resulted in indiscriminate arrests and brutal interrogation of Jeju islanders, claiming the lives of at least 30,000 individuals and leaving an indelible scar on the island’s history.

After decades of silence surrounding the violence under the shadow of the guilt-by-association system in South Korea, the Jeju 4·3 Incident Special Act was finally enacted in 2001 with the support of grassroots movements. This legislation sought to recognize the historical suffering of Jeju Islanders, and to uncover the truth about the events that transpired during this tumultuous period. Subsequent to the enactment, the then-President Roh Moo-hyun issued an official apology, a significant step towards acknowledging the gravity of the injustices committed.

In a more recent development, the Special Act underwent revisions in March 2021. These revisions encompassed several provisions related to the conduct of fact-finding investigations (along with reparations). These changes have been instrumental in facilitating our research at NARA II, underscoring the South Korean government’s ongoing commitment to seeking truth, reconciliation, and justice in the context of Jeju’s painful history.

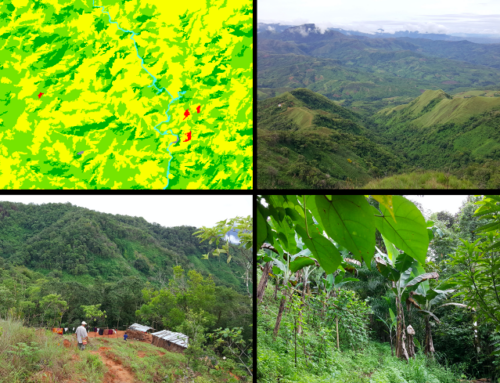

Our data selection process was guided by three primary criteria. Firstly, we prioritized records that explicitly mentioned Jeju Island and had relevance to the armed uprisings, conflicts, and the subsequent suppression of Jeju 4·3, covering the years from 1945 to 1954. Secondly, our focus was on records that provided a comprehensive depiction of the circumstances, policies, and significant events that unfolded on Jeju Island throughout the period of the violence. Finally, we homed in on records that offered insights into the policy changes within the US military government in Korea during this period. These criteria served as the cornerstones of our approach as we navigated through the extensive archive at NARA II.

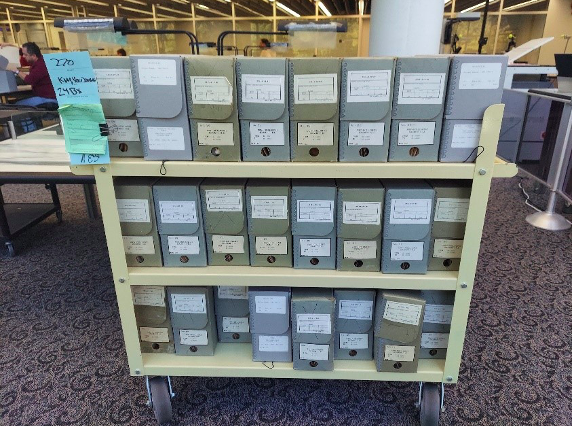

A cart of document boxes at NARAII. Photo by Youjoung (Yuna) Kim.

Throughout the research, it became evident that tools of knowledge, including lists and captions, played a pivotal role in the process of identifying discrepancies within the records. For example, we utilized a list of events encapsulated in the Jeju 4·3 Investigation Report, which serves as an appendix summarizing the progression of state violence. We conducted an examination of approximately 1,000 boxes from the “Army Intelligence Document Files” series (Record Group 319). Within this extensive collection, we found that approximately 380 textual records produced in 1948 had been classified and kept from public view, revealing a gap extending from May 1948 (following the Jeju uprising in April) to October 1948 (marking the initiation of the South Korean government’s scorched-earth operation on the island).

Moreover, in our examination of the “Photographs of American Military Activities” series (Record Group 11), we referenced the investigation report’s list of events to establish links between the photographs and their respective events. Simultaneously, we harnessed information contained in the photographs’ captions, which provided details regarding the names of places and production dates. Even in light of the gap within the textual records produced in 1948, we were able to unearth photographs tied to the suppression of the armed guerrillas during the events of Jeju 4·3 in that same year based on these tools of knowledge.

The National Committee for Investigation of the Truth about the Jeju 4·3 Events. 2003. Jeju 4·3 Investigation Report. Seoul: The National Committee for Investigation of the Truth about the Jeju 4·3 Events. Photo by Youjoung (Yuna) Kim.

Other tools of knowledge, including tables, were also helpful in the organization of the records. As we sifted through the extensive collection of records and cataloged scanned images of the materials, we constructed a table in an Excel spreadsheet. To ensure a systematic and accessible organization, we inputted the pertinent information, adhering to NARA II’s record classification system. This information encompassed details such as record group, entry number, series, box number, production date, institution, and location. Simultaneously, we applied a corresponding structure to the digital materials, arranging them into folders aligned with the hierarchy established within the table, encompassing record group, entry number, box number, folder, and item.

The little tools of knowledge employed in our research—including lists, captions, and tables—helped us to locate and organize data. Not only did they serve as aids in cross-referencing and verifying existing information, but they also facilitated a systematic organization of our findings. These tools provided a clear roadmap for pinpointing the precise location of materials stored at NARA II, thus ensuring their accessibility for future reference as needed. This methodology not only streamlined the research process but also laid the foundation for efficient data management.

As a researcher with a specific focus on the collection of documentary evidence pertaining to historical events, the application of tools of knowledge became essential to circumscribe the scope of our collection within the constraints of a tight three-month timeline. This constriction was accomplished by establishing spatial limitations within Jeju Island and temporal boundaries from 1947 to 1954. The decision-making process regarding the acquisition of particular records was not solely predicated on the systematicity constructed through predetermined criteria. It also entailed an element of informed conjecture, leveraging the utility of tools of knowledge such as lists, captions, and tables.

Moreover, these tools of knowledge were instrumental in our endeavor to reconstruct a narrative of Jeju 4·3, shedding light on the intrinsic relevance of the US military government in Korea to the unfolding violence. The records contained within NARA II are dispersed across various record groups, as they were initially organized by their respective producers and production dates. However, as these records find their place within our mirror archive, selected through the lens of our predefined criteria and with the aid of these tools of knowledge, they re-narrativize the events surrounding the violence of Jeju 4·3 by illustrating the relevance of the US military government in Korea.

These “little tools of knowledge,” as discussed by Becker and Clark (2001, 1), help us to decipher the archive, thus revealing the implications of the records within the vast milieu of big data. They serve as vehicles to uncover and recover the myriad expressions of the past and futures woven into the fabric of the archive (Blouin Jr. and Roseberg 2011, viii).

References

Becker, Peter and William Clark. 2001. “Introduction.” In Little Tools of Knowledge: Historical Essays on Academic and Bureaucratic Practices, edited by Peter Becker and William Clark, 1-34. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Blouin, Francis Xavier, and William G. Rosenberg. 2011. “Preface and Acknowledgement.” In Archives, Documentation, and Institutions of Social Memory: Essays from the Sawyer Seminar, edited by Francis Xavier Blouin and William G. Rosenberg, vii-ix. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

National Archives. 2021. “About the National Archives of the United States.” Last modified March 18, 2021. https://www.archives.gov/publications/general-info-leaflets/1-about-archives.html.

Youjoung (Yuna) Kim is a PhD candidate at the Department of Anthropology, Johns Hopkins University. Her dissertation investigates the bureaucratic procedures that are required to ensure the legal status of “victims” and “the bereaved” as outlined in the Jeju 4.3 Incident Special Act. Her project aims to illustrate how the official acknowledgment of such categories configures the ways in which people honor their ancestors, and how the South Korean state’s reconciliation project functions as nation-building intended to legitimatize state power. Her research has been generously supported by the National Science Foundation, Wenner-Gren Foundation, the Society for Psychological Anthropology, and various programs at Johns Hopkins University including the East Asian Studies Research Grant, the Women, Gender, and Sexuality Summer Research Fellowship, and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Summer Language Study Grants.

Cite As: Kim, Youjoung (Yuna). 2023. “Collecting Jeju 4·3 (Sasam) Records from the US Military Archive” In “data/Big Data in the field” edited by Naveeda Khan, American Ethnologist website, December 22 2023, [https://americanethnologist.org/data-big-data-in-the-field/collecting-jeju-4·3-sasam/]