Every weekday morning at approximately 8 a.m., a queue of hospital visitors forms in front of the registration desk at the Occupational Diseases Unit of Lokman Hekim Hospital,<sup>1</sup> located in the city of Y in Turkey. The visitors typically require three types of documents: employment eligibility reports, occupational disease certificates, and periodic examination reports. Inspired by anthropological studies that examine the role of documents in the establishment of bureaucratic facts (Das 2020; Hull 2012), I discuss in this reflection how barcode labels distribute the laboring body as a medical object among hospital actors.

The patient-workers visiting the Lokman Hekim come from various industries—ceramic manufacturing, automobile factories, shipyards—as well as the expanding gig economies of supermarkets and warehouses. At the hospital, these worker-patients undergo a comprehensive evaluation process, which I call a diagnostic circle. As they make their way through this process, doctors, nurses, laboratory technicians, and administrative staff register clinical evaluations, diagnostic categories, laboratory findings, and consultation notes into the patients’ medical records. These records are then forwarded to insurance boards and labor courts (if workers decide to initiate an occupational disease claim) to determine the eligibility of worker claims for care and compensation. Additionally, these records are utilized to generate statistical data for the contentious annual reports of the Turkish Social Security Institution on occupational diseases.

Given the long trajectory of occupational disease certificates across various medico-legal institutions, this essay limits itself to the hospital site and takes up the role of scannable barcode labels, one of the mundane filing technologies used in the establishment of the diagnosis of occupational diseases.

My analysis of the role of filing technologies in the diagnosis of occupational diseases builds on eighteen months of fieldwork in Turkey, where I studied the intersecting trajectories of law and medicine in the (under)recognition of silicosis among ceramic workers. Between 2017 and 2023, I followed workers and their families as they attempted to navigate a range of medical, bureaucratic, and legal institutions in order to have their ailments recognized. Through participant observation at the Occupational Diseases Unit of Lokman Hekim Hospital, I explored how doctors collected, recorded, and measured the medical evidence relating to occupational diseases. I attended hearings at the labor courts in lawsuits filed by workers with silicosis. I have found that despite the expansion of the legal rights for workers in health litigation in Turkey, only a tiny fraction of workers with occupational lung diseases are granted compensation through hospitals and courts. One of the many factors for this low rate of success in worker health litigation is the complexity of establishing the diagnosis of occupational diseases. Doctors must reconstruct the afflicted worker’s body in relation to workplaces with diagnosis entailing that the laboring body is made knowable and translatable into a medico-legal idiom.

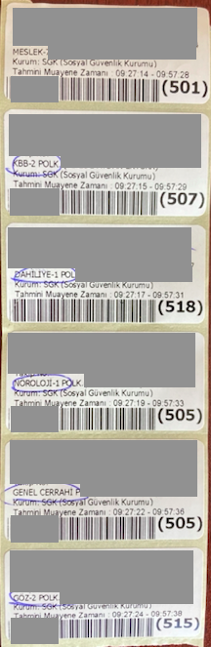

One filing technology used in the production of knowledge at the hospital for the assessment of worker bodies is the scannable barcode label. A typical barcode includes information on the time of the appointment, ID number, protocol number, insurance type, date of birth, the primary specialist overseeing the patient, and the consulted branch.

A Lokman Hekim nurse helping a patient carry out the pulmonary function test. Photo by author.

The barcode is primarily intended for preventing identification errors within medical tests, consultations, patient specimens, and so on. Yet, I argue that the barcode is also intrinsic to how doctors make diagnoses that allow bodies to be translatable into the registers of forensics and law. Barcode labels prepare the worker’s body “as a project to be worked on” (see also Good 1994) by forging the movements of patients and the practices of hospital staff in the diagnostic circle.

The registration desk serves as a starting point for a worker who comes to the hospital to learn whether her condition can be documented as an occupational disease. Here, visitors are first registered and handed a sheaf with multiple stickers of the patient’s barcode, each to be used by a specific unit of the hospital. Next, they are asked to visit the “Archive Unit” of the hospital. At the archive, they must leave their identity cards; thereafter, they cannot reclaim their IDs without a note from the attending physician. Through the collection of IDs at the archive, in a sense, the hospital ties workers to the diagnostic circle.

Next, each worker receives a large paper envelope with a sign reading “Medical Archival File.” One of the barcodes from the barcode sheaf is attached to the file on the spot. The patients then move to the clinic to consult with the “Work-related and Occupational Diseases Specialists” assigned to their name. The Occupational Specialist collects the illness story of the worker. If the worker is suffering from silicosis lung disease, the specialist typically asks for consultation from the chest diseases department, chest-x-rays, pulmonary function tests, and (in most cases) high-resolution computerized tomography.

A typical barcode sheaf used in the Lokman Hekim. (Identifying information is erased on purpose). Photo by author.

The specialist then picks up the sheaf of barcodes and one by one marks with a pen the subspecialties that the patient needs to visit for consultation. She reverses the barcode sheaf and notes down on the back of the barcodes the laboratory tests wanted from the patient. With the handwritten instructions in hand, the patient leaves the clinic and visits one by one the units assigned to him. At each unit, the attending staff members such as consulted physicians or laboratory technicians remove one of the barcode stickers from the sheaf.

After the diagnostic circle is completed, the patient revisits the specialist they saw at the beginning of the diagnostic circle. Specialists review the laboratory findings and consultation notes to evaluate the patient’s state. If they think the laboratory findings and consultation notes are enough to arrive at a diagnostic decision, they usually start typing their assessments and final diagnostic decisions. The specialist then asks the patient to leave the file for the “health committee” that will give the final decision on the diagnosis of occupational diseases. The specialist picks another barcode and sticks it onto a document that allows the patient to pick up his ID card left at the beginning of his visit, freeing him from the diagnostic circle. With his file and the specialist’s note, the patient leaves the file for the health committee, then picks his ID from the archive, and exits the hospital. At this point, the passage of the worker and the barcode around the diagnostic circle comes to an end. Thereafter drawing on the encounters and information gained through the interactions with the patient, doctors and hospital staff engage in further evaluations, writing practices, consultations, and so on.

So far, I depicted an ideal picture of the pathways of afflicted workers inside the hospital. Many of the stages within the diagnostic circle can be interrupted and complicated by problems emanating from the condition of the patient (e.g., a patient might be traveling from another city, may lack financial resources, etc.) or the glitches in the day-to-day organization of the hospital, or the sheer lack of information and resources necessary to further the medical examination.

Instead of focusing on such broader problems in diagnostic and treatment processes, in this essay, I tried to show how barcodes serve as the units upon which the separate components of diagnosis can be inscribed. Echoing the humility of bureaucratic documents (Hull 2012), barcodes as “little tools of knowledge” tend to recede into the background (Becker and Clark 2001). Barcodes prepare the laboring body as a project to be worked on and facilitate the movement of workers around the diagnostic circle. Through attention to the barcodes vis-a-vis the laboring body or the file, we see how the worker moves from being a unified body into an assembled one, from illegibility to semi-transparency.

Notes

[1] The name of the hospital is a fictitious one.

References

Becker, Peter, and William Clark, eds. 2001. Little Tools of Knowledge: Historical Essays on Academic and Bureaucratic Practices. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Das, Veena. 2020. Textures of the Ordinary: Doing Anthropology After Wittgenstein. New York: Fordham University Press.

Good, Byron J. 1994. Medicine, Rationality and Experience: An Anthropological Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hull, Matthew S. 2012. Government of Paper: The Materiality of Bureaucracy in Urban Pakistan. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Zeynel Gül is a Bridge to Faculty Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Illinois Chicago. His research examines the classification and documentation of occupational lung diseases at the intersection of law and medicine in Turkey.

Cite As: Gül, Zeynel. 2023. “Barcodes as Little Tools of Medical Knowledge” In “data/Big Data in the field” edited by Naveeda Khan, American Ethnologist website, December 22 2023, [https://americanethnologist.org/data-big-data-in-the-field/barcodes-as-little-tools-of-medical-knowledge/]