I suspected that Saturday March 14 would be my last weekend in London before returning home from fieldwork. Only three weeks into my archival research on colonial asylums in present-day Tanzania, it was also it was my first time in the UK. While the COVID-19 outbreak garnered attention around the world during this time, I remained enthusiastic about continuing my work and exploring the city. Fears of COVID-19 not weighing heavily on my mind, I chose to visit the the National Portrait Gallery in Trafalgar Square. Here, surrounded by British and foreign tourists, I encountered portraits of people whom I have long admired: Shakespeare, Darwin, Wesley. It felt surreal to see in person paintings I had only seen in textbooks and the internet.

I left the museum, which sits next to Trafalgar Square. Exiting, I heard the latest Lady Gaga song emanating from a Bluetooth speaker set up by a street dancer hoping to impress and earn money from passers-by. A person dressed in a Pikachu outfit was similarly hoping a young child would beg their parents for one pound to take a picture together. Young teens climbed on the famed lions as tourists took pictures of Nelson’s Column, Westminster Abbey and the Palace of Westminster – the seats of British religion and government behind it on the skyline. Still adapting to life in London, I was comforted by such a familiar scene, having spent hours in New York’s Washington Square Park while visiting friends who live there.

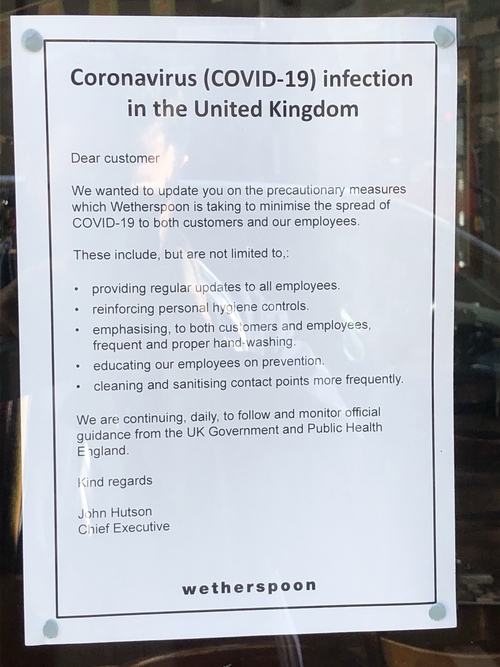

As I took in the scene, my phone buzzed. A message from my mother read, “UK now added to travel ban.” I looked across the street at the Square, teeming with activity, people unaware, and perhaps unaffected, by the ramifications of the USA closing its border with the UK, with few exceptions. While I was fixated on reading the links inundating my phone, shaken and concerned, activity on the Square remained alive. Standing there, I was reminded of friends and family back home, whose emails, texts, and social media posts indicated businesses were closing down, places of worship were cancelling in-person services, universities were moving classes online, and everyone was being required to work from home. Many back home, including my friends and family, were trying to figure out how to practice “social distancing.” Leaving the square to return to my flat, I saw posters lining restaurant windows and subway platforms offering disease prevention advice: Wash your hands!

Being in London amidst a pandemic is to participate in a broader history of public health responses. In the broader narrative of public health, epidemiology, and epidemics, London is considered a place of mythological beginnings. Epidemiology frequently traces its origin to John Snow, a London anesthesiologist, and the cholera epidemic in the 1850s (Altschuler, 2017). Snow discovered that the handle on the Broad Street water pump was the site of transmission and convinced local authorities to turn off the pump. Eventually, the cholera outbreak came to an end. Enshrined in the London School of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene’s atrium, the pump is a testament to Snow’s status as a founding father of modern public health approaches.

Over 150 years later, I spent the beginning weeks of the spread of COVID-19 in London, watching Londoners respond to a different disease outbreak, one on a much larger scale than cholera. During my three weeks in London, the outbreak moved from global emergency to epidemic to pandemic. As the World Health Organization reclassified the outbreak, the world watched and reacted as public health and medical officials, politicians, and citizens decided on how to respond to the virus. The responses have varied across the globe, different countries have operated on different timelines, with many arguing that the UK’s approach has been the least aggressive. The closing of the USA-UK border was one event among many over the course of my three weeks in London that had me reevaluate whether to remain in the UK or to go home. While there was some panic buying, the grocery stores near my apartment were still stocked with the toilet paper that I saw missing from the bare shelves in the pictures my US friends sent me. As I saw universities close down in the USA, like dominoes falling one after the other, UK universities remained open longer. I wondered what this meant for me. State and local governments back home mandated the closure of businesses and offices, leaving employees to work from home or get laid off. Yet watching each of these events, I decided to remain in London to continue my archival research as my concerns were assuaged by the British news, new friends, and my flat-mate.

The tipping point to my return to the USA came on March 16 with two coinciding announcements. The first came from British Prime Minister Boris Johnson, who announced that, like other parts of the world afflicted by COVID-19, the UK would begin to engage social distancing practices. He encouraged closing bars and theatres, avoiding public places, and to continue the shift towards working from home. People reacted quickly: within hours performances were cancelled, pubs and restaurants closed early, and the grocery store shelves bare, all items having been purchased. The second came from my committee members, whose emails urged me to return home as soon as I could. Two days later, I boarded a nearly empty flight from Heathrow to JFK with mixed emotions: while knowing it was the right decision, I was heartbroken over having to leave the field, for which I worked tirelessly to obtain funding, and uncertain of what would follow my fourteen day quarantine. Yet, the uncertainty over leaving was buffered some by the comfort of knowing I could cuddle my cat again.

While the US and the UK timelines were only days apart, I felt stuck in a liminal space where the boundaries to “home” and “the field” were no longer as clear I was used to them being (Gupta & Ferguson, 1997). As the emergency responses moved more quickly in the USA, being in the UK had felt stable. My ability to stay in the UK, however, was deeply dependent upon the decisions made back home: which borders would be closed? would my university require me to come home? which governmental response will reduce my likelihood of getting sick? Constantly checking the BBC and the New York Times websites for news updates, and my email for university notifications, I felt that, amidst the global pandemic, the spatiality on which that fieldwork is predicated was shrinking (Clifford, 1997). In the middle of the pandemic, home made an unprecedented claim on “the field”: the politics of home superseded the politics of the field as leaving the field in the middle of a crisis was no longer isolated to particular situations and field sites, but applied to nearly all research. And perhaps COVID-19 is reminding us of this in ways we may have forgotten: even when invoking the global in global health or global development that imagines particular forms of connectivity (Caduff, 2014:107; Fassin, 2012), home and the field come to mutually constitute each other when fieldwork becomes contingent in different ways on the politics and political economy of home.

Now, under quarantine at my parents’ house, the spaces of (field)work and home are being remade. But in returning, I’m reminded that the comforts of home – my cat, scotch on the rocks, and reactivating my Hulu account to watch The Golden Girls – remain constant.

Acknowledgements: My thanks to Laura Cox, Alfredo Rojas, and Abbey Warchol for comments on this essay and a WhatsApp group that also blurs the lines of fieldwork and home. And to my parents, who welcomed me back with barely 24 hours’ notice.

References:

Altschuler, Sari. 2017. “The Gothic Origins of Global Health.” American Literature 89 (3): 557-590.

Caduff, Carlo. 2014. “On the Verge of Death: Visions of Biological Vulnerability.” Annual Review of Anthropology 43: 105-121.

Clifford, James. 1997. “Spatial Practices: Fieldwork, Travel, and the Disciplining of Anthropology” in Anthropological Locations: Boundaries and Grounds of a Field Science, edited by James Ferguson & Akhil Gupta, 185-222. Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press.

Fassin, Didier. 2012. “That Obscure Object of Global Health,” in Medical Anthropology & its Intersections, edited by Marcia Inhorn & Emily Wentzell, 95-115. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Gupta, Akhil, & James Ferguson. 1997. “Discipline and Practice: “The Field” as Site, Method, and Location in Anthropology” in Anthropological Locations: Boundaries and Grounds of a Field Science, edited by James Ferguson & Akhil Gupta, 1-46. Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press.

Cite as: Dougan, Bryan M. 2020. “On Home & Field in a Pandemic.” In “Pandemic Diaries” Gabriela Manley, Bryan M Dougan, and Carole McGranahan, eds., American Ethnologist website, March 27, 2020. [https://americanethnologist.org/features/collections/pandemic-diaries/london-on-home-the-field-in-a-pandemic]

Bryan M. Dougan is a doctoral candidate in anthropology at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill.