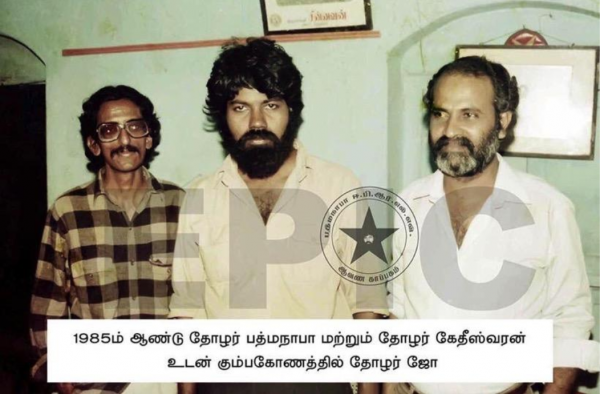

The Tamil caption reads “In 1985, comrade Joe with comrade Padmanabha and comrade Ketheeshwaran in Kumbakonam.” The image is watermarked EPIC (Eelam Peoples Information Centre) which was the news-service of the undivided Eelam Peoples Revolutionary Liberation Front (EPRLF). The two comrades in the picture were both killed by the LTTE in later years. With thanks to Balasingham Skanthakumar for help on the background.

etween April 2017 and his death in February 2018, the veteran Sri Lankan activist Joe Seneviratne met Harini Amarasuriya for a series of remarkable interviews in which he recalled his life and set down his views on the people and events he had encountered on the way. Joe was born in June 1943, four years before independence in February 1948. He is one of that generation of activists, as Jayadeva Uyangoda pointed out in a celebrated essay twenty years ago, whose personal biography is coeval with the unruly biography of the independent nation-state known as Ceylon until 1972, and since then, Sri Lanka (Uyangoda 1997). These are the people whose stories we are documenting as part of our bigger project on the anthropology of dissent and conscience. This short essay examines the often complex relationship between political dissent and intimate relations through the example of one, particularly gnarly and indomitable, life. That life can be seen to be divided between a commitment to revolution and solidarity with the comrades, and pulling against this, other kinds of commitment – to home, to partner, to children. The question it presents, and which we address in the broader project, is how much these contradictory pressures end up leaking into each other’s domain. Do painful splits with the revolutionary’s parents require the same kind of affective work as painful splits with the comrades? Does a commitment to radical change necessarily threaten the conventional commitments to home, partner, and children?

Joe Seneviratne’s political roots extend into the left politics of the early and mid-1960s:

I was aware of injustice from my school days, injustice about finance, student organisations, protests, beating, questioning religion, big problem. It was an urban school with children of all religions. We got punished, but that gave us courage. I was taken to Dematagoda police for trying to strike in school. I didn’t tell my father about the police. I was 15/16 years old. I read Soviet and Chinese literature; I read about Latin American experiences. These were inspirations: Che, Mao, their life stories. I read Maxim Gorky and Dostoevsky. I was influenced by literature but was not exposed to Western literature because there were no translations.

As an A-level student, he joined a Communist youth movement, participating in a Marxist Study Circle, and testing the limits of his father’s domestic regime. There were splits in the home and splits in the Party.

There were all kinds of people from different levels. The classes went on till late. So there were conflicts with my family for not being at home. Once when I came home, my father had given my plate of rice to the dog, saying this dog is better than you. Then I challenged him. I said, my house is not here, but the whole world, and I left home. By then the CP had split. The party said they could train me and then they put me to work with trade unions. I went with the Peking Wing, which was more revolutionary. The Soviet Wing was reformist.

Joe was by no means an uncritical member of his wing of the movement. With other comrades he worked on an internal critique of the party and its strategy. That critique was not well received, but in the process Joe learnt an important lesson about his erstwhile comrade, the future JVP leader Rohan Wijeweera:

72, Malwatta Road, Dehiwela. This was where some of us lived. We used to meet there and discuss till the early hours of the morning, and we prepared a document to hand over to the party’s central committee, an analysis of class etc. For the party to rethink its class strategy. Wijeweera was part of all this, but he refused to sign the document… He said I don’t have to sign. We didn’t understand at that time. We were so foolish. We didn’t understand that kind of [in English] political maneouvering. We saw the world in a very flat way, the relationships between people. We were sensitive. If I don’t trust you how can I do politics with you? Those friendships were very strong. How can we mistrust one of our comrades? Someone who had made so many sacrifices for the party?

The authors of the critical document were duly expelled from the party and Joe lost the small income he received as a party “full-timer.” Wijeweera went on to lead two violent assaults on state power, in 1971 and again in 1987-1990. In the second of these, his followers targeted leftists like his former comrade Joe who were seen as traitors because of their support for a peaceful resolution of the country’s ethnic civil war.

Joe lived through some very violent times indeed. He was part of a generation which came of political age in the 1960s. The old left-wing parties in Sri Lanka, with their patrician leaders and proletarian bases, were steadily losing their political grip in that decade: the LSSP and CP joined Mrs Bandaranaike’s coalition government in 1964. The ostensibly Trotskyist LSSP split, with the mainstream party expelled from the Fourth International for its apostasy in joining a bourgeois government. The CP meanwhile also suffered its own split in the wake of the Sino-Soviet divide, with a rival Peking Wing party, led by Shanmugathasan, emerging in 1964. This was also a decade in which young people found their political voice, especially in and around the campuses of the country’s relatively young university system. Needless to say, faced with a choice between the “revisionist” Old Left and the “revolutionary” Peking Wing, young radicals gravitated to the Peking Wing. Their tactics and aspirations also changed. While the Old Left had combined trade union activism with parliamentary politics, the young were increasingly attracted by the example of the Cuban revolution, a political transformation conceived as a great adventure, as a small band of young would-be guerrillas take to the hills to build a movement from the periphery. Capturing state power by violent force was not merely seen as a feasible strategy, for many of this generation it attained a certain self-evident quality.

In his interviews with Amarasuriya, Joe moved back and forth across his life, tacking between his childhood, his years as a young party militant in the early 1970s, then as an NGO organizer with the cross-ethnic Movement for Inter-racial Justice and Equality (MIRJE), into the wild years of the 1980s, when he was first imprisoned under the Prevention of Terrorism Act as part of a radical group known as Vikalpa, and then re-emerged as a minister, complete with office and official vehicle, in the short-lived North-East Provincial Council.

In parallel with the talk of splits and jail, and running for his life to India, there are other more modest, but equally telling, themes running through Joe’s story. One is age and the responsibilities of age. Joe was considerably older than many of his comrades in the heady days of the 1980s, and acutely aware of the expectations of his wife and children. More than once he records his sense of being torn between the demands of the comrades and needs at home: he was working as a teacher when he was offered the job at MIRJE; Joe’s wife reminded him that he was at last in a position eligible for a pension; Joe joined MIRJE instead. This intimate tension connects to the more pervasive relational grammar of solidarity and splits, which enabled some of his most remarkable moves. The 1960s splits in the left movement in Sri Lanka are the first condition of political possibility for Joe’s political life. His scepticism towards the cheap glamour of the violent politics of gesture gives him the option of a necessary distance in the times of greatest danger. His laconic use of religious analogies identifies the recurrent danger of authoritarian claims to solidarity and the need to leave some space to make one’s own judgements:

I got involved in the Vikalpa group. That became a church for Stalin. Then there are preachers. I could see that. I wanted to build a people’s movement not build churches. So I started questioning. Then I was called middle-class petty bourgeois. My brother had given me a pair of bell bottoms. I was scared to wear them because the comrades would have questioned me.

We found such a relational grammar present in other interlocutor’s stories, and one of our questions for our larger project is whether the intense friendships and equally dramatic ruptures in people’s intimate lives are continuous with the bigger political splits and solidarities of their time. Joe lived a life torn between the needs of the particular houses in which his father and his mother, and then his wife and children lived, and the house he called the world. But did it have to be this way? Is revolutionary commitment incompatible with the small intimate pleasures of everyday domesticity? Inserting Joe’s story back into a collection of biographies of his generation of revolutionaries will allow us to prepare a clearer answer to that question.

At Joe’s funeral in February 2018, one of the speakers told a tale of his time in jail with Joe in the 1980s. The story highlighted Joe’s generosity to his younger imprisoned comrades. Then, turning to the family mourners, he said, “I know Joe was not always able to be a good father or a good husband. But we had this great comrade, this great revolutionary, this great humanist. So we want to thank the family for this gift.”

Reference

Uyangoda, J. 1997. “Academic Texts on the Sri Lankan Ethnic Question as Biographies of a Decaying Nation-State.” Nethra 1: 7-23.

Acknowledgments

The research upon which this essay is based was generously funded by an ERC Horizon 2020 Consolidator Grant (648477 AnCon ERC-2014-CoG).

Cite as

Amarasuriya, Harini and Jonathan Spencer. 2019. “Tracing Conscience in a Time of War: Archiving a History of Dissent in Sri Lanka, 1960s-2000s.” In Tobias Kelly, ed., “The Intimacy of Dissent,” American Ethnologist website, April 15, 2019. http://americanethnologist.org/features/collections/the-intimacy-of-dissent/tracing-conscience-in-a-time-of-war.

Harini Amarasuriya is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Social Studies at the Open University of Sri Lanka.

Jonathan Spencer is Regius Professor of South Asian Language, Culture and Society at the University of Edinburgh.