When Febrianti Almeera started blogging in 2010 in Bandung, Indonesia’s education and technology hub, she did not know whether there were also other young women who identified with her experience of a muslimah hijrah: a woman who journeys from “being in the dark” (berada di kegelapan) – an expression for being ignorant and unknowing – to being aware that life is a continuous process of transformation and personal change leading to Allah. Yet, this experience became the foundation of a growing community of predominantly young and tech-savvy Muslim women who today operate across virtual and physical space. Great Muslimah, the name of the community also became the title of Febrianti’s first book. Today, she is a frequently invited speaker at Islamic lectures, TV shows, radio broadcastings, and other public events particularly oriented toward women in Southeast Asia. Febrianti applies the concept of hijrah, referring to the journey of the Prophet and his followers from Mecca to Medina in 622CE, to multiple contemporary topics. While her interpretation broadly applies to a neoliberal sense of personal growth, her most popular and frequent theme has recently been the subject of marriage. This is an outgrowth from her personal life, especially the popularity of a blog she started with her husband Kang Ulum thirty days before their wedding. Neither she nor her husband are religiously trained, which I argue amplified their appeal and allowed the blog’s tone to combine affective and hermeneutic content.

Logo from a blog called Prince of Heaven which publicly chronicled the engagement of two young Indonesians, Febrianti Almeera and Ulum.

PRINCE OF HEAVEN represents 30 writings that tell about: our journey as two persons that had already met but not quite knew each other, to the end … through a set of wonders of His scenario, we are determined to step into the most exciting phase of life, namely: MARRIAGE. (translation by the author)

The title of the blog “Prince of Heaven” (Pangeran Surga) and its motto “Wait in Obedience – Meet at the Right Time” (Menanti dalam Taat – Bertemu di saat yang Tepat) moved Febrianti’s young, female followers on a subject that seemed most important to them: romance and the ideal husband – a Muslimah’s personal “prince of heaven”. The blog asked and answered questions about the right time to marry, how to know whether one has chosen the right partner, or how to talk to one’s parents when the time has come to introduce the chosen one to them. It offered guidance in a combined register, simultaneously popular and religious. In the past decade, pious young people, often on college campuses, have turned to formal religious instruction for personal life choices, especially marriage choices. These environments have been decidedly offline, have emphasized formal religious rules, and have discouraged dating or even conversation between members of the opposite sex (Smith-Hefner, 2005). In contrast, Febrianti and Ulum’s blog encouraged engaged couples to get to know one another before marriage by discussing key topics, all in the spirit of religious devotion. Because Febrianti and Ulum offered their own lives as a model, readers witnessed a real relationship formed through commitment to each other, Allah, and Islamic rules, working together and presenting their views side by side. Female readers in particular admired a collaborative and communicative philosophy between partners.

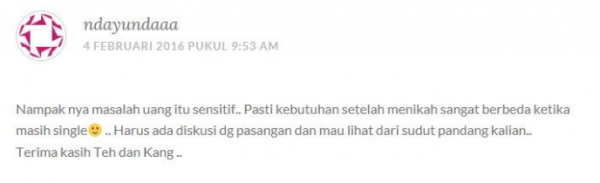

The couple promoted the project across social media starting with Instagram, Twitter, and Path to Facebook, where it received hundreds of likes and dozens of shares and comments. Amazed by the total number of almost 3.000 viewers for the first eight days, they decided to actively involve readers by conducting polls on the most desired topics and by directly answering the questions of their followers. In addition to the popular question of how to convince one’s parents that one is ready to marry, the topic that drew the most attention and commentary was whether or not a couple should discuss finances prior to marriage. This topic, users admitted, was sensitive and many wanted strategies on how to discuss money with a future spouse.

Comment to blog entry [H24] POLLING!; in English: Seemingly, the problem of money is sensitive. Surely, the needs after marriage are quite different from those when one is still single. There has to be a discussion with the partner and I want to see your point of view. (translation by the author)

In response, both Febrianti and Ulum respectively presented their experiences by writing about their first conversation on finances. While Ulum showed a relaxed attitude in his entry, Febrianti anticipated a “major disaster” (bencana besar) and described physical sensations such as heat and recurring trauma that “disturbed the stability of the heart” (pengganggu stabilitas hati). Notably, the blog itself was intended as a salve to those sensations. Febrianti described it as a way of stabilizing the heart and as a therapeutic means to stay aware yet calm while preparing to marry. She called it a “pit stop for emotional healing” (pit stop untuk emotional healing) and just like life – in the broad interpretation of hijrah – a stopover on one’s way to Allah. This resonates with other scholarship on the intersection of Islamic expertise and neoliberal reform in Indonesia. As Daromir Rudnyckyj (2010) has argued, entrepreneurs make claims to Islamic authority even if they lack formal religious training. James Hoesterey (2016) has shown that when religious entrepreneurs share their personal relationships publicly, they generate powerful affective bonds with their followers.

Different from other social media, for Febrianti blogging offered a venue to share feelings and personal experience in detail, which triggered the interest of a selected readership of young, urban, educated middle-class Muslim women who felt that life’s biggest questions should be considered through a religious lens but who were nonetheless concerned about managing their exposure to and consumption of social media. For them, Facebook and other social media generated “information overload” (English in original), suggesting that young women should select particular channels of communication to corresponded to their emotional landscapes. Small groups of women, for example, moved their online conversations to messaging apps like LINE that offered a more private space for them to share their personal stories and concerns. This allowed them more freedom and autonomy to choose which content to read and which people or groups to follow. By navigating different social media, they could minimize the stress of reading too much information on the Internet that was neither useful nor “in line with their objectives” (selaras dengan tujuan yang hendak dicapai), a strategy that they could classify as religiously consistent. This increased selectivity and the management of affections became integral to their social media competence that developed in the course of their daily struggles to become a “great Muslimah” – a Muslimah that is “beneficial to the universe” (bermanfaat bagi semesta).

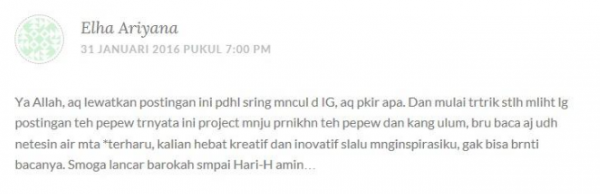

As readers’ comments indicated, Febrianti framed the blog as a simple account of her personal hijrah, adding to her credibility as a religious model in spite of her lack of religious authority, even as she offered up her private life for public consumption.

Comment to blog entry “Welcome to Our Sweetest Project!”; in English: O Allah, I missed these postings while they often appeared on Instagram. And became interested only after I saw more postings of Pepew [Febrianti] which turned out to be a project toward her marriage with Ulum. As soon as I read I already shed a tear you are amazingly creative and innovative and always inspire me, can’t stop reading it. May it run smoothly with Allah’s blessings until the last day, Amin. (translation by the author)

This emotional access defined the essence of Febrianti and Ulum’s project. Their joint and separate responses to questions about marriage – always presenting both sides of the story – made them feel authentic and balanced. Sharing accounts of their first acquaintance, including screenshots of their first WhatsApp conversations, readers appreciated what seemed like sincere intentions and animated them to continue reading their lengthy entries by activating affective registers in response to the critical perceptions regarding social media that a great Muslimah holds in the center of increased technological development in Indonesia.

Febrianti and Ulum positioned their blog to be appealing to this audience. More than personal experiences and reflections, blog entries were understood to contain practical lessons and inspirational notes to ponder upon the miraculous ways of Allah. Similar to the concept of Great Muslimah, Febrianti asserts that the Pangeran Surga project was ultimately Allah’s way to talk to people, through her and her husband, to find wisdom (hikmah) and lessons (pembelajaran). Using religious terminology to describe the value of social media, she described it as a mediator (perantara) for readers and a dowry (mahar) for the bloggers, even as it ultimately served as the basis for a book which the spouses intend to publish together. In the long run, the project inspired the couple to continue blogging on matters of self-improvement through the anticipated example of their future family life. By connecting her personal concerns to those which others experience, Febrianti has merged intimate and religious guidance into a popular secular form that readers treat as a means to overcome daily anxiety.

References Cited

Hoesterey, James B.

2016 Rebranding Islam: Piety, prosperity, and a self-help guru. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Rudnyckyj, Daromir

2010 Spiritual economies: Islam, globalization, and the afterlife of development. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Smith-Hefner, Nancy

2005 The new Muslim romance: Changing patterns of courtship and marriage among educated Javanese youth. Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, 36(3):441-459.

Cite as: Lengauer, Dayana. 2017 “Prince of Heaven: Blogging the Concerns of Great Muslimah” In “Piety, Celebrity, Sociality: A Forum on Islam and Social Media in Southeast Asia,” Martin Slama and Carla Jones, eds., American Ethnologist website, November 8. http://americanethnologist.org/features/collections/piety-celebrity-sociality/prince-of-heaven