Ibu Wiwin, a mother of two in her mid-thirties, lives in a comfortable gated housing community in the northern suburbs of Yogyakarta, Indonesia. Although her husband works for an international company and receives a salary far above the Indonesian average, she also owns a small beauty parlour. Wiwin enjoys a familiar daily routine of caring for her children and her business. However, in the last few years, her financial security and her daily schedule have not satisfied some of her deeper questions, leading her to seek out religious communities. Wiwin – like many of her middle-class friends – has joined Islamic study gatherings (majelis taklim) and become a regular reciter of the Qur’an. For example, while she waits in her car to pick up her children from school each day, she passes the time by reciting the Qur’an from a digital version saved on her smartphone. She has also joined a One Day One Juz (ODOJ) group where members connect through social media and commit to reading one chapter (juz) of the Qur’an every day, although she has only opted to read half a chapter a day because she is not yet an experienced reciter. But especially interestingly, whenever she feels she needs guidance, she directly contacts a preacher (ustadz) using messaging apps like BlackBerry Messenger or WhatsApp.

One might deduce from these new routines that Wiwin, and the friends in her various religious social media groups, aim to perfect their religious practice through these forums. Yet, when I asked her if this was true during a conversation in February 2015, she replied: “Actually not, the religious practice of most of these group members is already good. They are just filling their spare time. They are using their spare time to charge their hearts.” “Charging the heart” is a literal translation of nge-charge hati, a phrase composed of Indonesian (hati) and English (charge) words connected by Javanese grammar, i.e. the prefix nge, indicating an active verb, an action or performance. Wiwin further explained: “It’s like a battery, Martin. You have to fill it. Sometimes we are tired, all this routine, looking after the kids and so on. So it is important to charge your heart.”

My conversation with Wiwin and other interlocutors revealed that the process of nge-charge hati is a central part of the relationships between Islamic preachers and their (often female) followers, and that to a large extent these relationships are maintained by communication via social media. Wiwin’s favourite preacher is Ustadz Eko, not simply because he is a good teacher of the Qur’an but also due to his willingness to respond promptly to the messages she writes him. Wiwin struggles with bouts of grief in the wake of the death of her eldest child several years ago. Although she is happily married and has two healthy children, and is therefore not alone, she can feel isolated in her pain. In these moments, she contacts Ustadz Eko, who always responds comfortingly and without much delay. Wiwin has developed techniques to deal with her emotional ups and downs elicited by the loss of her child, yet she nevertheless needs the occasional “support,” as she says, from her preacher. In discussing why her ustadz can “charge her heart” when her husband cannot, she explained that although her husband is sympathetic, he is very busy, leaving the house for work early each morning and often traveling for business for days at a time. The sort of affective care Ustadz Eko provides via digital messaging therefore serves as a substitute for the face-to-face care she might receive from her husband.

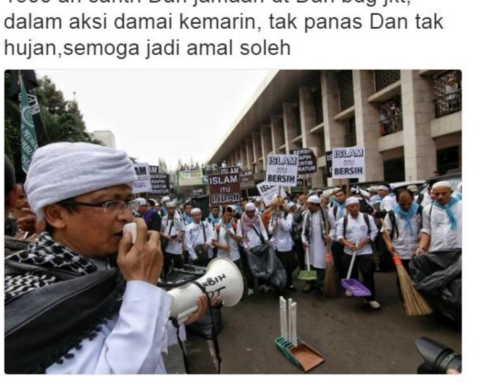

Indonesian Islamic preacher delivering insight into his social media activities, including exchanges on messaging apps with his followers. (Photograph by Martin Slama)

This form of mediated intimacy builds on older Indonesian encounters with the digital. Wiwin and her friends grew up in the first generation of Indonesians using the internet in the late 1990s and early 2000s as students in cities like Yogyakarta. Then, they had to go to public internet venues on university campuses or to internet cafes that were mushrooming at that time in urban Indonesia. They fondly recall an earlier era of internet chatting popular from their youth in which one could enjoy some anonymity and communicate in a realm distinct from their offline environment. These spaces were especially appealing because youth felt they could express their feelings openly, a genre of sharing that came to be called curhat, an acronym of curahan hati, which translates literally as “to pour out one’s heart.” For many students, the heart-to-heart conversations they had in internet chat rooms were their only opportunities to raise personal concerns, ranging from family problems, academic anxieties and the often complicated universe of love and romance. The curhat has only expanded with the growth of ubiquitous social media. Although these women have since married, had children, and now work as professionals, civil servants or entrepreneurs, and therefore may not need guidance on romantic choices, they nonetheless consider the curhat a comforting resource in the face of life problems.

Perhaps most telling is that the curhat has become increasingly gendered feminine. To “pour out one’s heart” is, strikingly, an acknowledgement of affective experience and need, burdens which Indonesian women with access to social media ameliorate through connecting to people they feel they can trust. Wiwin’s case demonstrates, however, a subtle shift from simply “pouring out one’s heart” to “charging the heart.” Whereas the curhat between peers in the chat rooms of the past suggested a one-way emptying of emotion to one’s peers, that has been absorbed by a more technical metaphor of recharging a battery, a process which requires a more powerful source to supply energy. This explains why middle-class women have sought guidance from preachers, rather than simply friends or family, and have, in the process rediscovered their religiosity. One might say that preachers’ active use of the heart-to-heart style means that the curhat has gone Islamic. Clearly, Indonesian women’s attempts to charge their hearts is a central part of their Islamic practice, along with the more recognizable components of piety such as regular prayers or fasting during Ramadan. For them, Islam is a valuable resource for managing their emotional lives. And as these practices become more popular among pious women, they become more prominent in Islamic practice generally, putting Muslim middle-class women at the center of processes redefining Indonesia’s Islamic field. Put simply, ustadzs cannot risk ignoring the emotional needs of their female followers. If they cannot find the right words at the right time, their followers will choose to charge their hearts elsewhere.

Cite as: Slama, Martin. 2017 “Heart to Heart on Social Media: Affective Aspects of Islamic Practice” In “Piety, Celebrity, Sociality: A Forum on Islam and Social Media in Southeast Asia,” Martin Slama and Carla Jones, eds., American Ethnologist website, November 8. http://americanethnologist.org/features/collections/piety-celebrity-sociality/heart-to-heart-on-social-media