“Sampai ke mana?” Or “How far could it go?” Imagining how far her self-portraits might circulate online, 30-year old Ani, a college graduate and entrepreneur in Yogyakarta, Indonesia, mused about the thrill and risk of using social media. Linking her posts to 4,700 followers with English language hashtags like #HOOTD (hijab outfit of the day), #hijabstyle, or #hijabista, she hopes her designs will be discovered. As a modest fashion designer, she aims to cultivate a broad, perhaps even global, digital following, yet risks entering national debates about the motivations women like her might harbor in having their images circulate online.

Tensions about the forms of speculation entailed in using social media have taken on two particular features in contemporary Indonesia: religious and gendered. Perhaps no genre has concentrated these debates more than the veiled selfie, popular on Instagram in particular. The selfie has therefore emerged as a social problem, as the site for facilitating something positive–love of modest fashion–and something negative–narcissistic claims to improving on Allah’s creation. The life of a selfie, once posted online, extends these risks because the subject cannot limit the image’s circulation. As one internet meme confidently stated it 2015, the pious selfie runs the risk of becoming “the female illness of our time.”

A self-portrait of a woman in pious style, the veiled selfie bears strong resemblance to selfies elsewhere. The subject of the photo is self-aware, is making direct eye contact with the camera and therefore the viewer, and once posted to a social media site, her hashtags intentionally connect the image to others with similar content. In this sense, the subject consciously uses social media’s algorithmic promise to introduce or maintain her virtual presence in a niche community with others who share her interests but whom she may never meet face-to-face. Also like selfies elsewhere, the subject of the pious selfie may be accused of anti-social, narcissistic impulses. Similar terms exist in both English and Indonesian describing the “desperate” and “thirsty” appetites of female social media users. Global admiration and vitriol for celebrities such as Kim Kardashian exemplify contrasting opinions about the genre’s allures and risks.

Pious fashion influencer Mega Iskanti, whose Instagram feed has 315,000 followers. Her indirect gaze dilutes the intensity of the conventional selfie.

However, unlike the broader genre, the pious selfie has particular risks. As Fatima Hussein (this collection) details, new digital forms have provided new terrain for religious expertise in Indonesia. Building on conversations that had been limited to online chat forums in the previous few years, a new genre of Indonesian male preachers whose reputations circulate and amplify through their own use of social media, have begun describing selfies as a uniquely feminine problem. Blending cosmopolitan psychological expertise with religious hermeneutics, Hizbut Tahrir preacher and self-help speaker Felix Siauw, posted a 14 point Twitter statement in 2015 in which he described women who post self-portraits in modest clothing as shameless, for their direct gaze into the camera, their mental anticipation of receiving flattery, and for showing off by altering one’s appearance (by using makeup and attractive angles). Framing his analysis in Qur’anic interpretation, and choosing Arabic terminology instead of Indonesian, Siauw described selfies as tabarruj (attention seeking display), and therefore a sin rather than an individual pathology.

While religious entrepreneurs such as Siauw have described the theological stakes of intentionally choosing to display feminine selves to others, social media posts by women have offered more complex interpretations. Some have focused on indirect sin. By contributing to others’ sins, rather than sinning themselves, subjects in selfies can nonetheless be morally culpable because while one might pose and post a self-portrait with the purest of intentions, one cannot control an image’s life once it becomes public. Other social media activists have chosen to provoke opposite conversations, by hashtagging FelixSiauw’s name along with their selfies in exposed or sexy poses. Each of these responses underscore what Patricia Spyer and Mary Steedly (2013) have observed about how images move, that some images lend themselves to reenframement or iconicity more than others. Women in headscarves consistently top that list.

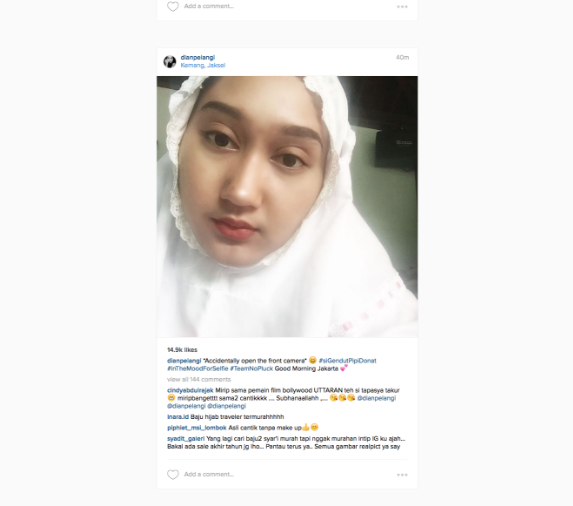

The timing of these Indonesian conversations is telling. As Karen Strassler has described, the past decade of post-authoritarian political culture in Indonesia has been saturated by a fascination with exposure, transparency and documentation (2009). Yet that same decade in Indonesia has also seen the rise of a related aesthetic that has emphasized the opposite of exposure—cover. Along with a rise of conspicuous consumption and Islamic style, the modest fashion industry has grown in financial and aesthetic prominence. Young designers who grew up with social media now find themselves reliant upon a marketing medium that requires constant content, content that can then be classified as sinful because of its circulation. Consider 26 year-old modest fashion designer Dian Pelangi, whose global reputation and 4.6 million Instagram audience began when, as a teenager, she posted daily selfies detailing her outfits on a personal blog. Now Creative Director of her eponymous company and identified as a modest fashion star by global tastemakers, she needs her images to circulate yet risks accusations of posing and profiteering. In short, she can be accused of insincerity. An Instagram post in December 14, 2015 highlighted this conundrum. A photo of her makeup-free face outlined by her white mukena (prayer covering), she captioned the photo as an “accident” taken by the front-facing camera on her phone during her morning prayers at home in Jakarta. The image was exceptional, evidencing her pious practice, yet minus her trademark false eyelashes and her famous smile. These features telegraphed sincerity yet underscored the glossy style of her usual images documenting her life of frequent international travel, often featuring products for which she is compensated to promote. Comments under the photo revealed her followers’ awareness of this contrast, repeatedly praising her courage to appear without makeup, asking her to post more photos of the type, and calling her “super Muslim” (Muslimah banget). This has been her most popular post to date.

Dian Pelangi’s December 14, 2015 “accidental” selfie.

These reactions recall Ani’s dilemma. Her desire for publicity as a professional run the risk of interfering with the reputation she, like Dian, requires for success as a pious designer. They both need their designs, and their images, to circulate widely in a national and transnational landscape in which women’s images may generate sin. As if in anticipation of these criticisms, Dian, Ani and many other Instagram users attempt to prevent accusations of insincerity by including hashtags that address specific aesthetic choices, such as the hashtag #teamnopluck, referring to the refusal to pluck one’s eyebrows in honor of not altering Allah’s creation. Similarly, a number of Indonesian Islamic print fashion magazines published articles during the peak of the 2015 selfie debate, reassuring readers with quotes from Islamic authorities stating that selfies are not forbidden as long as the intention is simply to document oneself without claiming to improve on divine creation.

That women in particular have been both drawn to and critiqued for documenting their covered appearances suggests that the dialogic qualities (Bonilla and Rosa 2015: 7) of social media cannot be separated from their spectacularity, a semiotic vulnerability that is uniquely gendered. The affective afterlives of moving images therefore index how the effervescence of social media is persistently paired to their capacity to control.

References Cited

Bonilla, Yarimar and Jonathan Rosa

2015 #Ferguson: Digital protest, hashtag ethnography, and the racial politics of social media in the United States. American Ethnologist 42 (1):4-17.

Strassler, Karen

2009 The Face of Money: Currency, Crisis, and Remediation in Post-Suharto Indonesia. Cultural Anthropology 24(1):68-103.

Spyer, Patricia and Mary Steedly

2013 Introduction: Images that Move. In Images That Move, Patricia Spyer and Mary Steedly, eds. Pp.3-40. Santa Fe: School for Advanced Research Press.

Cite as: Jones, Carla. 2017 “Circulating Modesty: The Gendered Afterlives of Networked Images” In “Piety, Celebrity, Sociality: A Forum on Islam and Social Media in Southeast Asia,” Martin Slama and Carla Jones, eds., American Ethnologist website, November 8. http://americanethnologist.org/features/collections/piety-celebrity-sociality/circulating-modesty