by Alia Ayman

The 1952 revolution was a turning point in Egypt’s history. The Free Officers succeeded in their coup, the monarchy was abolished, and Egypt became a republic led by Gamal Abd El Nasser in 1956. Nasser was particularly interested in bringing “culture to the people” as he would often say in interviews. He established the Ministry of Culture in 1958 first under the name of the Ministry of National Guidance and went on to consolidate the state’s reach into all areas of cultural and media production. As more and more young people became employed by the state, the boundaries separating the artist from the bureaucrat became increasingly blurry and tensions between art and propaganda began to fully emerge. Those tensions made themselves visible in a number of state funded films that were made by an early generation of documentary filmmakers active between the 1960s and 1980s. I focus here on one of those films, The Healer of Saint Catherine, directed by Ali El Ghazouly and produced by the state TV in 1986.

Cinema was seen by the Nasserist state as a crucial tool in fashioning the ideal national subject. By 1963, the state had nationalized almost all aspects of film production, distribution, and exhibition and created a new institutional infrastructure staffed by a young generation of filmmakers who formed the core of a national cinematic bureaucracy of unprecedented scale. Documentaries were a priority for the regime at the time, as indicated by the sheer amount of films produced by the state which had reached 1000—if not more—by 1968 according to a report issued by the Ministry of Culture that I was able to find as part of my research in the archives at Cimateque in Cairo.

The majority of the documentaries produced by the state between the 1960s-1980s that I was able to gain access to had one very interesting feature in common; unlike many documentaries produced in Egypt today, these earlier films often lacked a narrative arc. In other words, the formal logic of these works did not revolve around stories and characters, rather they functioned more like portraits or vignettes, and were driven more by the information they relayed and cultural practices they recorded than the stories they narrated. For example, the films of Ali El Ghazouly, one of my most prolific interlocutors, ranged from historical documentaries focusing on ancient Egyptian monuments, hieroglyphs, Islamic, and Coptic architecture in Cairo to more ethnographic films focusing on everyday life in remote Egyptian villages, the practice of herbal medicine in Sinai, copper excavation in Suez, and traditional fishing techniques. Even when a film was focused on a given character, as is the case with El Ghazouli’s The Healer of Saint Catherine (1986), the viewer mostly comes away with ethnographic insights about herbal medicine, desert landscapes, and Bedouin culture in Egypt and not so much about the character himself.

Still image from The Healer of Saint Catherine

Unlike the more recent infrastructure which encourages plot-centric documentaries with likable characters that circulate predominantly on the international festival circuit, an earlier institutional configuration (which still exists today) operated according to a very different logic. This was an institutional setting where official mandates and topics of national concern determined which films were made, who made them, and what they looked like. Documentaries at the time were valued primarily according to the information they relayed, the subjects they highlighted, and the way they were filmed. Stories, characters, and gripping plot lines were quite marginal, especially when compared with the central position occupied by the character driven documentary in the global cinematic landscape of the present.

Still image from The Healter of Saint Catherine

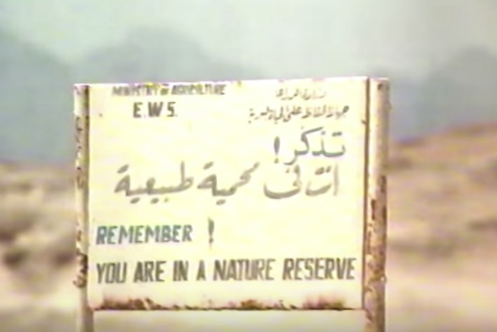

The Healer of Saint Catherine was produced by the documentary division affiliated with the state TV which was established in 1980. After holding many positions in documentary units across different public sector institutions since the 1960s, El Ghazouly worked as the director of the documentary division until he retired. In his capacity as the division’s director he would set the annual plan for films to be produced, commission other filmmakers who worked with him, and would also make his own projects. He distinguished between films made as part of the division’s annual plan and what he described as “freer films” which he would make out of personal interest. The Healer of Saint Catherine is an example of the latter. It is a passion project, funded by the state but not commissioned by a particular entity. El Ghazouly met the film’s protagonist when he was making a film called Sinai: A Gift of Nature which was jointly commissioned by the American oil company Conoco and the General Egyptian Petroleum Organization.

Still image from Sinai: The Gift of Nature

Unlike The Healer of Saint Catherine, Sinai was what El Ghazouly described to me as a more conventional documentary. When I asked him what he meant by conventional he explained that the norm at the time was to have “voice of god” commentary based on scientific and historical facts drive the film’s narrative from beginning to end. In that sense, The Healer of Saint Catherine was different in that the film’s narration was minimal and it came from the film’s protagonist rather than from an external commentator. In my interview with Hashem El Nahhas, another prolific documentary filmmaker who occasionally collaborated with El Ghazouly, he showed a lot of pride in the fact that he never used any commentary in his films, unlike what he described as the works of propaganda that relied heavily on the use of voice over. The same was said to me by another filmmaker of the same generation, Samir Auf, who saw in the absence of voice over higher artistic value and more fidelity to the language of cinema which he believed to be purely visual and aural, but never didactic. A formal feature of the films, namely the use of voice over, generated considerable debate among practitioners at the time and was a distinguishing factor between films that can be considered works of art and films that were dismissed as too didactic or propagandistic.

Despite the fact that the three filmmakers were civil servants for the majority of their lives and all their films were funded by the state, their position as filmmakers employed by the state bureaucracy did very little to undermine their artistic aspirations. They saw their films as works of art while at the same time acknowledging the constraints of the job which meant that sometimes they had make compromises. The simplistic schism I went in imagining between the bureaucrat and the artist was thus heavily undermined both by my conversations with those filmmakers and by the films themselves. And so, to conclude, at this phase of my research, the figure of the artist-bureaucrat emerges as an analytical framework of immense significance in order to understand the media world inhabited by this earlier generation of filmmakers. How is it that artistic autonomy and institutional constraints are navigated by filmmakers? And how can anthropologists of media be at once attentive to form without foregoing the broader networks and infrastructures that enable the making of the films being studied? These are some of the questions that I will be addressing as this research develops further.

Cite as: Ayman, Alia. 2019. “The Artist as Bureaucrat: Documentary filmmaking in Egypt, 1960-1980s.” American Ethnologist website, August 18, 2019. http://americanethnologist.org/features/reflections/the-artist-as-bureaucrat

Alia Ayman is a PhD candidate in cultural anthropology at New York University.