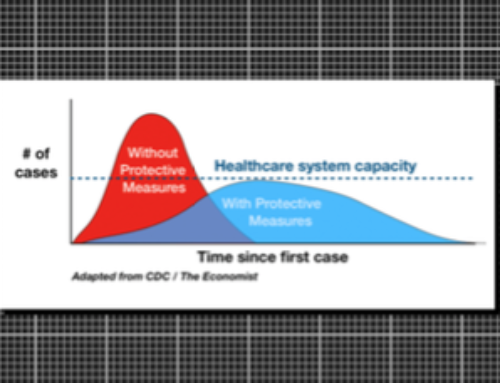

What kind of work is authentically essential? In the midst of a global pandemic, Americans have been introduced to new classifications of some work as essential. Almost as quickly as we adopted this new terminology to refer to the laborers who must leave their homes to care for others—the nurses, doctors, grocery store clerks, and janitorial staff —we began to publicly proclaim our support and gratitude for their essential work. Social media platforms in the USA and Europe have been an important part of this process, providing a place where millions of people have added hashtags like #thankyouhealthcareworkers and #stayhomesavelives to posts to encourage people to stay home so as to not overwhelm hospitals and healthcare workers. As professionals like hospital staff, postal workers, and gig economy laborers take on personal, bodily risks for the benefit of the social body, they are clearly and undeniably deserving of public gratitude and celebration.

The Non-Essential Workers

Yet as new categories of laborers are classified as essential, this prompts a related question: Who are the non-essential workers? How does the value of their labor shift in a moment of crisis? How are they responding to these shifts?

I study a group of people who do something that many others do not consider to be work at all: Instagram influencers. Influencer is a broad term, but it is often used to refer to young women, frequently of color, who promote products and services to large audiences on social media. Influencers can have hundreds of thousands of followers, not always on the basis of talent or skills external to Instagram, but as a direct result of their ability to create likable, attractive, and enviable content. Research on social media users with over 100,000 followers has suggested that “they imagined their audience as a fan base or community with whom they could connect or manage” (Marwick and Boyd 2011, 120). Influencers continually manage their social media output in line with the expectations of their audiences (both followers and corporate sponsors), as their income and professional identity require ongoing work of self-representation through images and text. One of the most crucial of these expectations is “authenticity,” or the perceived “realness” of an influencer. When produced successfully, authenticity blends desire and intimacy into a hydrid commodity-image composed of components of the influencer’s private life.

Authenticity is thus a magical mix of appearance and reputation managed through strategic forms of self-disclosure (Marwick 2013, 115). While influencers have always “worked from home,” selective glimpses into their homelives have also been the core raw material of their production process, a process which generates surplus value for sponsors out of the intimacy and labor of access to influencers’ lives. If, as Minh-ha Pham has argued, the work of presenting consumption on digital platforms is already misrecognized as “not work” (2015, 170) because of blurred boundaries between work and home, and work and play, that erasure further obscures the labor and even alienation influencers experience by offering unending access to themselves and their homes, sites that we know are also longstanding spaces of flexible, uncompensated, feminized work. With Americans now outsourcing their consumption to Instacart and Amazon workers, how might we analyze the work of those whose mediated private lives may also be precarious? Are they able to shift tones to make aspiration seem either therapeutic or serious in a moment when consumption itself feels frivolous and dangerous?

How to be Authentic in a Crisis

I find that navigating this shift in tones is proving challenging for many influencers. Having trained themselves for work in an era in which offering up parts of their private lives was part of a broader narrative of consumption as self-expression, their fluency in digital connection is meeting its limits. Some opt for humor, others long for an earlier era of elaborate beauty routines. Not all succeed. And because failure on a public platform can be intense, including mockery and shaming, their capacity to continue to generate content and more importantly, followers, can be difficult. For example, as “essential” has emerged as the heroic virtue of the pandemic, influencers are confronting questions like: How do you make your appearance seem “essential?” Can one navigate the affective terrain of an unprecedented crisis while selling luxury products on Instagram?

Ya Gotta Laugh

A twenty-something reality TV contestant turned stay-at-home mom is heavily pregnant with her second child. On her Instagram account, which has 622,000 followers and counting, she often gives advice about sustainable living, interior design, and skincare products. Many of her posts are tied to her paid brand sponsorship work (@bekah). On March 15th, she posted a photo of herself donning a face covering and blue rubber gloves. She is also wearing large sunglasses (indoors) and holding a “26-week” announcement board (as is typical of many Influencers sharing their “pregnancy journeys” with their followers) and posing next to several rolls of toilet paper. The photo is captioned: “Sometimes when you feel like crying, ya gotta laugh. #26weeks.”

A New York chef turned beauty and wellness guru with 126,000 Instagram followers shared a short video clip. She grins on camera, and the caption included is: “In my experience, it’s almost impossible to smile at someone without them smiling in return. So, here’s a video of me smiling at you, with the hope that you’ll find it in your heart… to smile back.”

Another influencer, a former fitness and bikini model who now shares messages about body positivity and self-acceptance to her 181,000 followers, tosses her head back and laughs for the camera. She is wearing a flattering sweat suit and raising her arms to adjust a matching grey baseball hat, exposing her midriff. The caption below explains that she hasn’t washed her hair in a week and has been wearing this same sweat suit for days. “Now I know why dogs get so excited to go on walks,” she writes, punctuating the message with the emoji smiley face that is laughing so hard it cries, “#socialdistancing and #stayhome,” (@maryscupoftea).

Staying Positive

These posts have tens of thousands of likes, and hundreds of comments from followers expressing gratitude for their humor and positivity during such a dark time. The three posts offer us a glimpse at the emotional labor that young women influencers often exert to produce authenticity and likeability for their audiences.

As feminist scholars have observed, women’s emotions and affective states have long been under scrutiny, and their physical appearance is frequently fused to that labor (Lorde 1981; Ahmed 2010). As of 2019, 84% of Instagram influencers were women, and as these three posts suggest, gendered affect is a crucial element of effective “influencing” (Statista 2019). But how should one feel about a pandemic? For influencers whose identity is wrapped up in notions of positivity—whether body positivity, joyful pregnancy, or self-love—conveying “negative” emotions like fear or sadness could jeopardize a carefully-honed reputation. On the other hand, if they are smiling, laughing, and carrying on like normal amid disaster, the sense of shared reality that “authentically” connects them with their followers—something vital to their work as human advertisement media—is at risk. They are caught in an emotional double-bind.

I Love You, But…

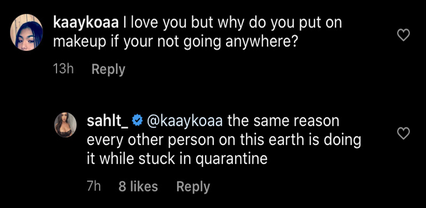

So, what happens when an influencer “gets it wrong?” Recently, a successful influencer (@sahlt_) posted a photo that was normal for her profile pre-COVID-19: she was wearing a tight pink dress (which she was also simultaneously advertising in the post for the brand of the dress), with slicked back straight hair, perfectly executed make-up, and dramatic false eyelashes. Alongside the numerous heart-eye-emojis and compliments on her outfit, figure, and make-up, one follower commented, “I love you but why do you put on makeup if your (sic) not going anywhere?”

Given that the “audience” for such elaborate looks are always virtual rather than face-to-face, why was this influencer reprimanded for doing her normal work? Is “normal” influencer work even possible in a pandemic? We might think that the influencer is being called out for advertising a dress at an inopportune moment. Interestingly, however, the comment is not about selling products, but the way the influencer appeared while selling products. The problem seemed to be that the influencer had failed to acknowledge a moment that not only requires staying at home, but also aligning one’s style in line with a growing global sense of tragedy. By failing to attune to this dominant mood, she came across as emotionally inauthentic. Self-promotion, the core stuff of an influencer’s métier, only succeeds if the self that is being promoted appears to be authentic. If the influencer appears to be affectively outside of the social world of their followers, they are no longer relevant. Recognizing this, the influencer responded by assuring the commenter of their shared reality: “stuck in quarantine” like “every other person on this earth,” she is merely putting on a (perfectly made-up) brave face.

I’m Just Like You, Follower

Exchanges such as these suggest a crack in the unspoken fusion of women’s appearances with the circulation of desire and cocreation of value that rests at the heart of socially mediated entrepreneurial projects. This is especially evident if an influencer’s aesthetic no longer resonates with an audience’s aspirations. Whereas a glamourous lifestyle may have once been a popular aspiration, those same followers may now simply aspire to staying healthy and employed. Followers seek emotional similarity, wanting their influencers to feel sad—like they do, like we do—in order to show connection, depth, and humanity. Finding the perfect balance of sympathetic but radiant positivity, expressing sadness and happiness with appropriately placed smiles and hashtags, requires skills most influencers are only now trying to cultivate. The new appropriate message, perhaps, would be something like this: “I’m just like you, follower. I also may not feel like washing my hair and want to stay in my sweat suit all day. Only I look this good and happy while doing it.” They might feel like crying, but they “gotta laugh” instead.

In this way, influencers try to showcase their emotional labor—their ability to mask sadness for the sake of their followers, to carry on despite everything, and in the process, reposition their work as something like a gift to each of us, a gift of joy that in times like now might be more than just charitable but perhaps, in their own way, “essential.” We, as followers, get to decide if we agree with them.

References:

Ahmed, Sara. 2010. The Promise of Happiness. Durham: Duke University Press.

Guttman, A. 2020 “Instagram Influencers by Gender 2019 l Statistic.” Statista https://www.statista.com/statistics/893749/share-influencers-creating-sponsored-posts-by-gender/.

Lorde, Audre. 1981. “The Uses of Anger.” Women’s Studies Quarterly 9(3): 7-10.

Marwick, Alice E., and Danah Boyd. 2011. “I Tweet Honestly, I Tweet Passionately: Twitter Users, Context Collapse, and the Imagined Audience.” New Media & Society 13(1): 114–33.

Marwick, Alice E. 2013. Status Update: Celebrity, Publicity, and Branding in the Social Media Age. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Pham, Minh-Ha. 2015. Asians Wear Clothes on the Internet: Race, Gender, and the Work of Personal Style Blogging. Durham: Duke University Press.

Cite as: Davenport, Gillian. 2020. “Good Vibes: The Complex Work of Social Media Influencers in a Pandemic.” In “Pandemic Diaries: Affect and Crisis,” Carla Jones, ed., American Ethnologist website, May 20 2020, [https://americanethnologist.org/features/pandemic-diaries/pandemic-diaries-affect-and-crisis/good-vibes-the-complex-work-of-social-media-influencers-in-a-pandemic]

Gillian Davenport is a MA student in cultural anthropology at the University of Colorado. Her research focuses on economies of influence, gender, and digital representations of self on social media platforms.