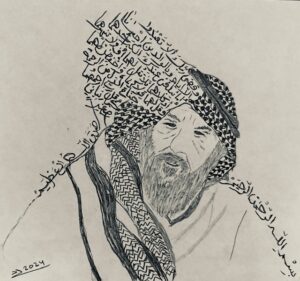

The Unforgotten. Artwork by Suhad Daher-Nashif (2024).

In many Arab countries where state and religion are closely linked, states rely on religious institutions to govern their populations and shape people’s attitudes and behaviors in all domains, including health management. In this way, religion as an institution has significant power to justify and maintain the existing political systems of order and discipline. Talal Asad (1983) points out the power of religious ideology in stabilizing existing controlling systems, structuring religious practices, and producing religious knowledge through religious figures such as scholars and jurists. In Unconscious and Body Language, Ali Zaiour (1991) refers to the power of the clergyman and his ability to influence and shape individuals, their thoughts, and their attitudes toward various issues in life. The clergyman’s ability to decide what is permissible and what is prohibited enables him to reach the deep feelings of individuals, including their feelings of guilt, regret, and fear of punishment.

Fatwas are a major religious resource for Muslims, and one tool that is used by Muslim religious institutions to shape Muslims’ behaviours and attitudes, including their health behaviours. People draw on religious resources when coping with illness and life stressors (Miller and Thoresen 2003), including neurocognitive disorders, such as dementia-related symptoms (Sayegh and Knight 2013). This essay presents how dementia and caregiving are framed, explained, and shaped in the Quran, Sunnah, and fatwas, thus illuminating the background of dementia caregiving modalities across the Arab region.

Fatwas are legal rulings announced by a qualified faqih/mufti (clergyman) in response to a question posed by a person or institution, or in response to emerging issues. Using fatwas to she light upon contemporary issues that have no reference in the Quran (the holy book for Muslims) or the Sunnah Nabawiyyah (statements and behaviours of the Prophet Mohammad [PBUH]) is common in Arab and Non-Arab Muslim countries (Asni and Sulong 2017, 2021). However, the referential basis of all fatwas is the Quran and the Sunnah. Contemporary issues such as organ donation and transplantation, IVF, plastic surgery, and more have been discussed in fatwas, which have allowed, regulated, and/or prevented these practices. For instance, in her study on forensic medicine in Palestine, Daher-Nashif (2019) addressed how fatwas, in the Arab region, were the main apparatuses used by the nation state to convince local populations that postmortem autopsy is allowed by religion if the goal is justice, medicine, and/or education.

Dementia, as an important and contemporary health issue, has been the topic of many recent fatwas. In a previous study on older adults and mental health disorders in Islam, my co-authors and I have explored how older age and mental regression are framed in Islamic holy texts, i.e., in the Quran and Sunnah (Daher-Nashif et al. 2021). We found that these texts shape belief systems and inform how people behave around older adults and people with dementia. However, we have not addressed fatwas as a disciplinary apparatus and a source of knowledge used by the religious institution to shape communities’ dementia care.

In this essay, I take up the concept of governmentality—described by Michel Foucault as the soft, non-aggressive, and invisible apparatuses that govern and control populations such that power is seen as rational (Foucault 1979, 1997)—to consider how dementia and caregiving are framed, explained, and shaped in the Quran, Sunnah, and fatwas. Governmentality has become a key analytic of many recent critical writings in cultural anthropology, including those on religion and faith in health and illness.

To collect the data from the Quran, I used the Indexed dictionary of the Quran (Abd al-Baqi, 1994). For the Sunnah, I have used Sahih Al-Bukhari and Sahih Muslim (Hadith collections used by Sunni Muslims) and, for the fatwas, I used the websites of the official jurisprudence institute (Dar al-Iftaa’) of each Arab country. Furthermore, the search included IslamWeb, the biggest global platform for fatwas and religious resources for Muslims, published by the Qatari Ministry of Religious Affairs, under the supervision of a committee of licentiate sharia scholars who are overseen by a mufti. I then applied a thematic analysis to identify the main topics related to framing and caring for dementia.

Framing Aging and Dementia

In Arabic, older adults are referred to as aged (mosin) or/and sheikh. In religious texts, these terms indicate two distinct meanings: The first is more of a social-religious status that reflects the person’s advanced knowledge in religion and wisdom associated with life experiences. The second reflects a physical condition related to progress in age. Aging, in the Quran and Sunnah, is described as the time when a person might lose the knowledge they have accumulated through life, as stated in Surah 16: “Allah has created you, and then causes you to die. And some of you are left to reach the most feeble stage of life so that they may know nothing after having known much. Indeed, Allah is All-Knowing, Most Capable.” (Quran 16:70; a similar description appears in Surah 22:5).

Characteristics of old age in the Quran include physical and cognitive weaknesses, and aging itself is framed as a disease. Cognitive regression is framed as a natural part of aging and a symbol of God’s power, as mentioned in the above verse. Aging and the loss of cognitive ability are also mentioned by the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) as the hardest of diseases to endure. He even prayed to God to protect him from these, saying: “O Allah, I seek refuge with You from cowardice, miserliness, and from being sent back to a feeble age” (Al-Bukhari, Book 16, Hadith 14).

Similarly, in fatwas, dementia is linked to progress in age, and patients are framed as those from whom “the pen is lifted.” This means they are not obligated, not held accountable for any action or behavior; in essence, because they lose their cognitive capacity. They are framed as those who are confused and have lost their minds. For example, one fatwa stated,

Dementia is a damage of the brain resulting from aging. The old sheikh may be confused and not able to distinguish between things, this makes him lacking capacity and hence he’s released from obligations. It is not madness because madness is one of the black diseases that can be cured but dementia is not […]. Despite the difference in meaning, they have the same status. Both are released from religious obligations, cannot buy and/or sell, and not judged or blamed for their behaviours (Fatwa 37606, 2003).

This framing also led many fatwas to exempt dementia patients from religious obligations, such as prayer and fasting. For example, a person asked if his elder father, who was diagnosed with dementia, must pray. The mufti’s answer was:

If your father reached the age of dementia and he’s confused, he does not have to pray, and if he does with some confusion it’s ok and he should not be blamed. If he wakes from his dementia at the time of prayer for enough time, then he has to pray because the mind is the basis for obligation (Fatwa 38495, 2003).

In Arab-Muslim countries, civil law combines Positive laws (human-made) and Sharia laws (Islamic law that derives its provisions from the Quran and Sunnah). In these resources, legal capacity (dhimma) equals to the ability of a person to oblige, be obliged, and conduct one’s affairs by oneself. In addition, it refers to the power that qualifies individuals (ahliyyah) to secure and exercise rights and privileges while being culpable of depravity, and has two levels of capacity: the potential of an individual to acquire rights and obligations (ahlıyat al wujub); and the capacity to exercise, execute, and perform such rights and duties (ahlıyat al-ada’). For example, in Fatwa 372460 (2018), the mufti has advised a man and said:

If your aunt no longer knows how to pray on her own, then she is excused, and it is not obligatory for her to pray because the obligation has been removed from her…she’s also excused from fasting and praying because the pen is lifted from her.

Caring for Older Adults with Dementia

The Quran and Sunnah state clearly and repetitively that it is an offspring’s duty to take care of their parents, whether or not they suffer from dementia. Several Quranic verses dictate filial commitment and respect. The main verse cited in the Sunnah and fatwas is the following:

The Lord has decreed that you worship none but Him, and that you be kind to parents. Whether one or both of them attain old age in their life, say not to them a word of contempt, nor repel them, but address them in terms of honor, and lower to them the wing of humility, out of mercy, and say, My Lord, have mercy on them, as they raised me when I was a child (Quran 17: 23-24)

Moreover, neglecting parents and not caring for them is considered in Islam as a major sin. An example is in Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) statement when he said:

Damn you! Damn you! Damn you! When he was asked, “Who was damned, O Messenger of Allah?,” he replied, “He, who has elderly parents, or even only one of them is old, but he did not attempt to enter Heaven by providing good care to his aged parents” (Sahih Muslim, 2009).

Within Islam, caring for parents is rewarded either in this earthly life or in the afterlife. Similarly, fatwas instruct that caring for parents with dementia is the child’s duty. Even when care becomes difficult, institutionalization is not an acceptable solution unless it is in the older adult’s best interest. For example, a man living abroad posted a question about his 84 year-old mother and his brother who does not care for her. The fatwa stated the following: “It is your duty as her son to take care of her, not to institutionalize her, but if this is for her best interest—to avoid her suffering—then institutionalize her, but you have to be sure about the good care of her at that place” (Fatwa 411274, 2020).

Part of caring for parents with dementia is to respect them and not make them feel weak by reminding them of their prayers. Instead, it is recommended to leave them, not to insist, not to correct them if they mix up the order of prayers or pray at the wrong time. My close analysis of forty-four fatwas addressing the care of parents and patients with dementia allowed me to arrange them into three main categories: caregiving in general, practices related to religion and religious obligations, and finances. As part of caring for people with dementia, fatwas have recommended the following: “Make Dua for them (Ask God to help them); don’t be honest (Tawriya) to them” (Fatwa 107235, 2008). For example, if they ask after somebody who has passed away, “don’t be honest and insist that they have died; be empathetic, bear with them and don’t shout/shush/mock them; and don’t pay for their care with their money, unless you don’t have it” (Fatwa 225553, 2013). Moreover, fatwas state that no one (including the spouse of the person diagnosed with dementia) is allowed to use any of the dementia patient’s property, including money, for anything other than their care and well-being; not even for building a mosque or for charity. For example, a mufti posted an answer to a question on using the money of a mother with Alzheimer’s Disease, stating the following:

You do not have the right to dispose of your sick mother’s money except for what is in her best interest and to develop it in permissible ways, and to pay zakat on it every year, and it is not permissible for you to do charitable works from it unless she has the right mind and commands you to do so, so you must implement it within the limit of one-third, as it is what the seriously ill patient has the right to dispose of. From his money without compensation (Fatwa 65183, 2005; more examples can be found in Fatwa 255649 (2014) and Fatwa 452677 (2022).

Fatwas also dictate that the money of persons with dementia should be used only by their proxy (assigned by Sharia court). For instance, when one man asked if he could use the salary that his mother (with dementia) receives as a widow from the government, he was given the following answer: “The proxy is not allowed to use or manage any part of the money of the person with dementia, even for charity. The money is hers only, and no one has the right to take any of it, unless she gives it by her desire when she has episodes of capacity” (Fatwa 105185, 2008).

Finally, fatwas also highlight that dementia patients are eligible for inheritance—like everyone else—when their proxy will be responsible for managing this.

Conclusions

Fatwas address questions that arise in the everyday practice of caring for parents and patients with dementia. This reflects the fact that communities are actively seeking answers to issues not addressed in the holy texts. As a modern health issue, a significant number of fatwas have been dedicated to dementia and to how to care for persons living with dementia. In Muslim communities, where fatwas are a major resource of knowledge, official fatwas have the legal status of a law. Therefore, fatwas extend and empower the government’s reach, including in the domains of health and illness. Governmentality regulates human conduct through multiform techniques, procedures, and agents (Baptista 2018), and fatwas are among these techniques. Health care institutes and providers should be aware of peoples’ perceptions and beliefs, and build a culturally competent approach to dementia care among Muslim communities (Daher-Nashif et al. 2021; Sayegh and Knight 2013), as religious belief may play a major role as either a barrier or a motivation for seeking diagnosis and treatment, thereby shaping the quality of life of people with dementia.

Looking at the fatwas related to dementia, we can identify some of the key concerns related to the topic that arise from Muslim communities in the Arab region. People want to understand and be reassured about how dementia is framed within the official healthcare system. They also want to ensure that they will not be held morally accountable if their parent or patient does not perform their prayers, fasting, or other religious obligations, and to understand how God expects them to behave when their loved one is diagnosed with this condition. Concurring with Geertz’s (1975) argument that religion impacts individuals by establishing moods and motivations, the Quran, Sunnah, and Islamic fatwas can offer a legitimate and motivating reference for caring for patients and parents with dementia.

References

Abd al-Baqi, Muhammad. 1994. The lexicon of indexer for pronunciation of the Holy Quran. Damascus and Beirut: Dal al-Fakhr (in Arabic).

Asni, Fathullah, Faisal Husen Ismail and Jasnig Sulong. 2017. “Fatwa coordination between states: analysis of the practices of standardization and its method in Malaysia.” Journal of Fatwa Management and Research 9 (1): 86-109.

Asni, Fatullah, Ahmad Yusairi and Amirah Izzati Umar. 2021. “The role of The Perlis State Mufti Department in restraining Covid-19 through fatwas and legal guidelines.” International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences 11 (10): 311-328.

Asad, Talal. 1983. “Anthropological conceptions of religion: reflections on Geertz.” Man 18 (2): 237-259.

Baptista, João Afonso. 2018. “Governmentality.” In The International Encyclopedia of Anthropology. Wiley: Online Library.

Daher-Nashif, Suhad. 2019. Forensic Medicine in Palestine: Anthropological Study. Institute for Palestine Studies: Lebanon (in Arabic)

Daher-Nashif, Suhad, Suzanne H. Hammad, Tanya Kane and Noor Al-Wattary. 2021. “Islam and mental disorders of the older adults: Religious text, belief system and caregiving practices.” Journal of religion and health 60 (3): 2051-2065.

Geertz, Hildred. 1975. “An anthropology of religion and magic, I.” The Journal of Interdisciplinary History 6 (1): 71-89.

Sayegh, Philip and Bob G. Knight 2013. “Cross-cultural differences in dementia: the Sociocultural Health Belief Model.” International Psychogeriatrics 25 (4): 517-530.

Miller, William R. and Thoresen, Carl E. 2003. “Spirituality, religion, and health: An emerging research field.” American Psychologist 58 (1): 24.

Zaiour, Ali. 1991. The Cultural Unconscious and Body Language and Non-Verbal Communication among Arabs. Dar al-Talia: Lebanon (in Arabic).

Suhad Daher-Nashif (MSc.; PhD) is Lecturer (Assistant Professor) in Sociology and Anthropology of Health, and Programme Director for MSc. in Global Healthcare Leadership in the School of Medicine at Keele University, United Kingdom. She is originally trained as occupational therapist and medical anthropologist and is currently completing her second MSc in medical education. Daher-Nashif applies her interdisciplinary background and approach in health and social sciences to dismantle the intersectionality between science, society, politics and bureaucracy throughout health and death practices in the MENA region. Her research fields are post-mortem practices, medical education, and mental health (mainly among older adults). Daher-Nashif is passionate to build curricula of humanities and social sciences in health professions education settings and to establish feminist qualitative methods in biomedical contexts. Follow her work at Suhad Daher-Nashif – Google Scholar.

Cite as: Daher-Nashif, Suhad. 2024. “Framing of and Caring for Dementia in Arab-Muslim Communities” In “Aging Globally: Challenges and Possibilities of Growing Old in an Unsettling Era,” edited by Magdalena Zegarra Chiappori, American Ethnologist website, 7 August 2024. [https://americanethnologist.org/online-content/framing-of-and-caring-for-dementia-in-arab-muslim-communitiesby-suhad-daher-nashif/]

This piece was edited by American Ethnological Society Digital Content Editor Katie Kilroy-Marac (katie.kilroy.marac@utoronto.ca).