I have long been wistful for my first field site of Yemen, but as I have been unable to return there, I decided to go to the island of Soqotra instead. Although technically part of Yemen, it has escaped the military violence that has engulfed mainland Yemen in the last decade. I was also drawn by Nathalie Peutz’ excellent ethnography, Islands of Heritage: Conservation and Transformation in Yemen (2018), which investigates how Soqotran islanders are developing strategies of protection of their heritage of distinctive and wonderfully weird endemic plants, which inspired UNESCO to declare the Soqotra Archipelago a natural world heritage site in 2008. As Peutz describes, these conservation strategies related both to wildlife and to the distinctive Soqotri language are now part of the fabric of everyday life on the island, along with the incipient ecotourism industry.

My current research project focuses on walking, quantified and otherwise. So far, I have focused primarily on walking in cities like New York, Singapore, Toronto, and Jerusalem, exploring the tension between technologies of quantification (Fitbits or Apple Watches), ideologies of fitness, and urban mobility. A walking tour in Soqotra, I thought, would expand my horizons of walking in rougher terrain. I joined a walking tour limited to 10 other participants, run by a group of Italian guides, committed wilderness hikers with years of experience in Soqotra. They hired a very talented local cook, local tour guides met us at each destination, and Soqotran drivers provided transportation to the various sites, from mountains to sand dunes to the seaside. So great was my desire to return to Yemen that I agreed to stay in a tent, which amused my son greatly as I had never agreed to camp in Canada. On our daily excursions in Soqotra, every member of our group had portable pedestrian kits (I’m inspired here by Ito, Okabe, and Anderson, although their work deals mostly with how “kits” are used for urban movement). We each had a small knapsack with sunblock, refillable water bottles, tissues, and cellphones. Cellphones functioned here exclusively as cameras as the internet reception was zero in most places. This was an odd blessing: we had been advised by the tour organizers to just let our colleagues and families know we would be out of touch for a week, allowing us to focus on Soqotra rather than swamping them with photos.

Walking in Soqotra was also a way for me to examine a different kind of walking that was oriented outwards toward the natural environment rather than inward toward one’s quantified self. While my Apple Watch might have been eager to supply data about the movement of my body, it was soon clear that for walking in Soqotra, more important was one’s eyes, one’s stamina, and help from one’s peers. I realized how limited the Apple Watch is in capturing the communal effort of wilderness walking due to its exclusive focus on the movement of the wearer. Indeed, it was more helpful for me to try to model my steps on the walking tactics of our guides, trying to embed a new “technique of the body” in Mauss’ sense. It became clear to me that it wasn’t strictly a technique of only my body; my body was helped by following in the footsteps of others and gratefully receiving their helpful hands and advice, verbal and nonverbal. This sensory attention—to that of my own body and those of others—shaped my walking more than the recording of my steps. I discuss here three kinds of walking: sand dune climbing, lagoon walking, and mountain hiking. The first was done barefoot, the second in water shoes, and the third in hiking shoes.

Getting it over with

Our group was comprised of walkers from the US, Canada, Britain and Australia; most of us had or were currently residing in the Middle East, in Oman, Dubai, and Iraq. On most of our walks, Elena, our Italian guide, arranged for a local Soqotri guide, different on each walk, to lead the way, while she closed off the rear, to make sure no one was left behind. I tried to stay relatively close to the front of the group. I was struck by how much of moving up hill involves mental fortitude as well as physical strength. As soon as the hike steepened, I lost interest in what my watch counted: I could only think about reaching the top. Elena cautioned us against sitting down to rest because our muscles might be more difficult to rouse again when we tried to stand up. It was also mentally hard to rise, so I remained standing as we paused for breaks, gulping lukewarm water. I felt guilty as our Soqotri guide was fasting for Ramadan, not able to quench his thirst until sundown, although at one point, he joined us in taking a welcome splash in a shallow pool.

On our first steep hike, a British man was one of the first to opt for a break in the first shady cave we found, blaming jet lag. When he emerged a few hours later, he showed that while clearly not an athlete, he was roused by his competitive spirit. He told me later that the only way he finished the walk was by creating a kind of personal gamification. Motivating himself every hundred steps, he methodically counted each one, and then signed himself up for another hundred steps. He was not recording the steps with his phone or watch or Fitbit, but still used counting as one method of encouragement, by setting a small achievable goal and then renewing it. As I listened to him, I realized that my primary motivators in walking as in other activities are shame or guilt, a legacy that lingers despite me being a fallen Catholic. I did not want the shame of having to say I could not make it to the top of the hill, nor did I want to feel guilty about inconveniencing anyone by disrupting our collective walk with a theatrical collapse.

Skills of Sand Dune Walking

Sunrise on the sand dune.

I felt an enormous sense of achievement for what I had accomplished, especially considering the fact that I had grown up being the last person anyone seemed to want on their sports team.

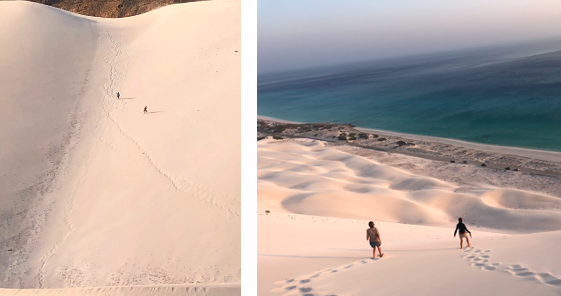

The descent was much easier and much more fun, but the downhill running induced by gravity can be treacherous because one’s feet tend to sink very quickly.

Watching the descent (left) and going down the dune (right).

Walking up

The walk in the region of the village of Homhil was tough; it was already hot and dry at 9:30am when we began walking up the steep hill, trying to avoid the bristly vegetation near the path. Before long, it felt like not just an ordinary walk, but an awfully long walk. A couple of our walkers backed out almost immediately, and our driver, Yahya, took them back to the camp. Others took refuge in a cave half way up the hill, reminding me of my earlier fieldwork in the blazingly hot coastal town on the Red Sea, where nothing was as welcome as a bit of shade. The rest of us slogged on. It was not particularly dangerous but it was hard, and one had to pay attention so as not to slip on the scree. We were ecstatic to make our way to our first dragon’s blood tree, which is one of the distinctive endemic plants for which Soqotra, which some call “the Galapagos of the Indian Ocean,” is famed:

Dragon’s blood trees on the hill (left) and dragon’s blood tree (right).

It was a relief to rest in the shade of the dragon’s blood tree, under their distinctive woven branches:

Dragon’s blood trees, made for shade.

Lagoon Foraging Walk

More novel (to me) walking occurred in the Detwah lagoon, trying to avoid stingrays while looking for other sea creatures. This kind of walking was not even recorded as walking by my Apple Watch, which kept buzzing me to ask me if I was still walking. This distracted me from learning how to walk on the slippery rocks at the bottom of the lagoon. I thought of Christina Scaramelli’s opening description of having to learn how to walk in muddy swamps during her field research on the Turkish wetlands. It was my first time in swim shoes, which did seem to help me maintain my balance, although Fahmy, our guide, seemed to be gliding, barefoot, with an impressive grace. We left our knapsacks behind but when I realized, quite far out in the lagoon, that I was in danger of dropping my phone or getting it wet if I tipped over, I got a bit anxious. Again, foot placement was key, although I couldn’t see with any effectiveness under the water, feeling around with my toes for a relatively flat surface. Seeing under the water is a learned skill; Fahmy found so many creatures under the water that I did not even notice. I was reminded of how I was told I needed to develop “new eyes” when I was learning how to forage for edible plants in Palestine. “Note to self: don’t think you could survive alone in the wild,” I thought, as we marvelled at the creatures Fahmy discovered with such ease:

A little crab (left), a starfish (middle) and a sea urchin (right).

The “Are We There Yet?” Walk

On our last walk, advertised by Elena as the hardest walk of the trip, our numbers were few. As we started our ascent at around 3:30 in the afternoon, trying to avoid the worst heat of the day, I quickly realized that Elena wasn’t joking. It was still pretty hot. Fahmy, our guide who had been so adept in showing us the sea-creature wealth of the lagoon, was cautioned by Elena not to go too fast. Fahmy, so sure footed on the slippery lagoon walks, was equally impressive in his capacity to skip up the mountain in bare feet and a futa, the knee-length skirt commonly worn by Yemeni men. I really struggled at first, panting like a dog. At one point, I turned around, but realized that with my signature talent for getting lost, I wouldn’t be able to make it down the mountain alone and I did not want to ruin the walk for everyone else. Fahmy seemed to sense my hesitancy and took me under his wing, gently coaching me. He wordlessly held out his hand, miming to me to take off my knapsack, which he then carried for me. I was grateful as after 15 minutes it felt like it weighed 50 pounds. Kamal, the husband of April the geologist, also helped me, by pointing at the steep ground, saying softly, “Here, here,” indicating the best place for me to put my feet. I also kept reciting to myself, “You can do it, you can do it,” which seemed kind of silly, but whatever gets you up the hill, I suppose. I felt a little like the “are we there yet?” kid. At least three times when we paused, I had optimistically decided we were there, but no. At long last, Elena announced that we had made it. We looked down at the ocean below us. Fahmy handed me my bag, and without being at all conscious of it, the first thing I did was refresh my lipstick, always part of my portable pedestrian kit, which made Elena and Fahmy laugh out loud.

Anne and Fahmy at the top of the mountain.

I did not even mind their making sport of the “lipstick anthropologist” as we made our way gingerly down the hill, trying not to slip on the scree. I was still glowing with victory!

Acknowledgements

My first thanks are to Fahmy, who graciously made saving me from certain death seem both effortless and fun. I also appreciate the help and laughter of Elena, April, Kamil, and Yahya. My ongoing conversations with Nathalie Peutz about Soqotra have been an inspiration and a pleasure. Thanks to Bruce Grant and Paul Manning for their comments, and to Vaidila Banelis who shares my love of Yemen. I appreciate the comments and suggestions of the AES reviewers and Katie Kilroy-Marac.

Anne Meneley is a Professor of Anthropology at Trent University. She works on the anthropology of walking (quantified and otherwise), and human-nonhuman interactions in plant materialities. Her work has appeared in American Anthropologist, Annual Review of Anthropology, Cultural Anthropology, Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space, Ethnos, Gastronomica, Jerusalem Quarterly, and PoLAR.

Cite As: Meneley, Anne. 2023. “Walking in Soqotra”, American Ethnologist website, 25 January 2023 [https://americanethnologist.org/online-content/essays/walking-in-soqotra-anne-meneley/]