When the Fourteenth Dalai Lama, along with his administration and more than 80,000 Tibetans, fled to Nepal and India following China’s military retaliations against the Tibetan uprisings of 1959, they thought exile would be temporary. Instead, as China’s military invasion transitioned into a colonial occupation, exile became a long-term state of affairs. Under such bleak circumstances, Tibetans reconfigured sovereignty in the form of sovereignty-in-exile, at a distance from the colonial developments inside Tibet. Central to this project was the work of kinship—both the maintenance of well-established forms and the activation of new ones. Prior to exile, Tibetan kinship alliances had tended to function along biological/affinal (clan) and regional (hometown) lines. As I show in this historical and ethnographic essay, the conditions of exile also worked to configure new kinship ties along national lines—communities in exile became family to each other, and in turn, the nation itself was imagined as family.

In exile, schools became key sites in which these novel forms of kinship and belonging were cultivated. In 1960, the Dalai Lama’s administration opened nurseries for children in exile that later became boarding schools (Dalai Lama 1991). Students from this school eventually became adults who sustained the next phase of exile for Tibetans escaping the policies of the Cultural Revolution that were imposed upon Tibet. Today, there are over 70 Tibetan refugee schools in Nepal and India that have graduated over 25,000 students. These educational institutions, which were developed, run, and attended by Tibetans, both sustained and fostered new forms of solidarity and citizenship that in turn bolstered the project of sovereignty-in-exile.

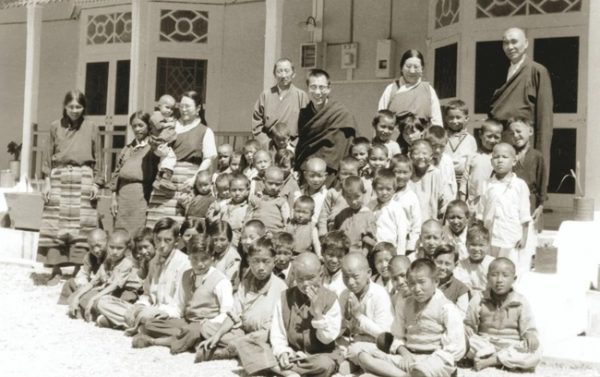

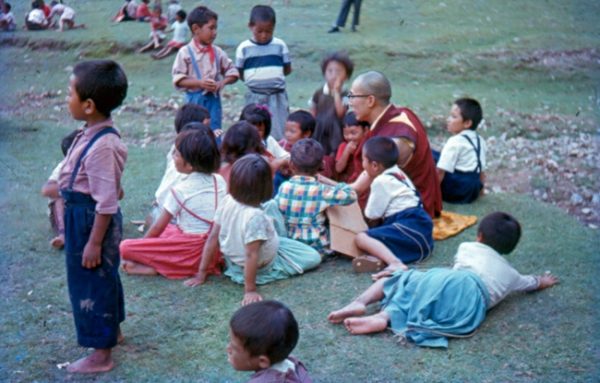

His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama at the center, his sister Tsering Dolma to his right with a woman helper, mother Diki Tsering to his left, 2 members of his administration, and children of the nursery in the 1960s (top). His Holiness at a school anniversary picnic with children in Dharamsala (bottom). Photo (bottom) courtesy of Sonam Tsering.

A Brief History of a Nursery that Became the Tibetan Children’s Village

When the schools first opened their doors, the Dalai Lama charged his older sister, Tsering Dolma, with the responsibility of overseeing the nurseries for Tibetan children in the mountains of Dharamsala, India. Tsering Dolma had her own biological children, but when she became head of the nursery, she became a parent to all. The Dalai Lama frequently attended school events, giving speeches at the yearly anniversary of the nursery that would later become the Tibetan Children’s Village (TCV) and paying regular visits to the children and staff. The school acquired the name “Upper TCV” when another school, which was called “Lower TCV,” was developed in lower Dharamsala. The children nurtured at this school during these early years of exile returned as adults to work as teachers and administrators in the expanding school system, thus shaping the next phase of exile. They also became government officials, civil servants, and welfare officers of the Tibetan government and the newly built refugee settlements. Additionally, these former students had children of their own, becoming parents to the next generation of Tibetans in exile, as well as an adoptive family and community to those escaping the Cultural Revolution in Tibet during the 1980s and 1990s. Today, many of these schools’ first students, whom I interviewed between 2015 and 2020, are retired. They view their services to the Tibetan refugee collective and Tibet at large as duties based on their own experiences at school. They credit the Dalai Lama, Tsering Dolma, and many others at the school for the nurturance and guidance they received as children.

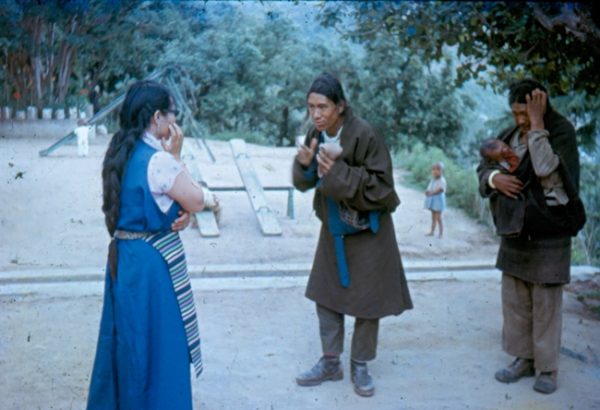

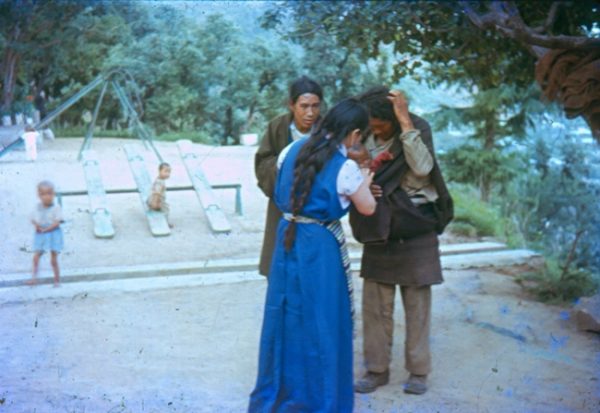

Image 03 and 04: Tibetan parents bringing a child to Tsering Dolma, head of the nursery and the Dalai Lama’s older sister in the early 1960s. Photos courtesy of Sonam Tsering.

Three distinct generational groups of students have attended the schools since they were first opened in 1960. I talked to members of each group about their experiences in order to track the development of school and the larger community in exile. The first generation, discussed above, consisted mainly of youths who were either orphans or semi-orphans between the 1960s and 1970s. Orphans were children who had lost their parents either during the invasion, amidst the exodus, or in the refugee camps in exile. Semi-orphans were children with living parents, but who lived and grew up at school due to the safety concerns and financial hardships that characterized life in exile. Parents also felt a sense of agency when they sent their children to be educated under the Dalai Lama’s guidance, as this was an important pathway for sustaining Tibetan cultural and political identities and securing a national future.

The second generation of Tibetan students consisted of adolescents who came from Tibet at the end of the Cultural Revolution. Between 1985 and 2008, parents smuggled their children out of Tibet to enroll them at schools in India before themselves returning to Tibet. Members of this second generation remain unable or unwilling to return to Tibet because their status as returnees from exile means they are subjected to heightened surveillance by the Chinese state and face difficulties finding employment. As adults, most have thus remained in exile, far from their biological families in Tibet.

Finally, the third generation of students to attend the schools was comprised of adults who were born in exile and graduated from the schools between 2000 and 2010. Unlike the two previous generations, this group includes graduates who were never separated from their parents.

School as Family, Family as Nation

In January 2020, I met with Tapsang, a teacher of Tibetan language and literature at the Dalai Lama Institute for Higher Education in Bangalore, India, which is the newest branch of the TCV system in higher education. Tapsang was part of the second generation of Tibetan students in exile. Like others of his generation, Tapsang’s story is one of escape motivated by the Dalai Lama’s renewal of Tibetan sovereignty, as well as the crafting of new bonds of kinship in exile.

The death of Mao in 1976 signaled the end of Cultural Revolution in Tibet. In the period that followed, travel restrictions between Tibet and India were briefly lifted, allowing many to reunite with family in exile and see the Dalai Lama. They brought with them stories of the widespread death and destruction that had taken place in Tibet during the Cultural Revolution. Tibetan exiles in India also returned to Tibet, but their stories more often told of hope and renewal. They brought news of the Dalai Lama’s government, of monasteries that had been demolished in Tibet being reconstructed in India, and of the success of the schools. In this way, word of a national Tibetan community-in-exile made its way back to Tibet. These stories, according to Tapsang, made life in exile seem exciting and hopeful. Moreover, many of Tapsang’s classmates at the Chinese public school he attended in Tibet had already escaped. The combination of these stories and his classmates departures aroused Tapsang’s curiosity. Aware of the free education and accommodation the Dalai Lama and his government was offering Tibetans escaping from Tibet, Tapsang decided to make the journey to exile. So, in 1995, when he was 13 years old, he escaped from Lhasa into Nepal and then made his way to India. In leaving Tibet, Tapsang also left his family. In this, he was not alone. As a member of the second generation of students in exile, his story was shared by many.

Tapsang told me that it was neither family pressure nor a lack of opportunity that motivated him, since he came from a modest background. Instead, he felt enticed by the hopeful prospects of the national project that exiled Tibetans were building under the Dalai Lama’s leadership. In recounting his successful escape to Nepal, Tapsang described the Tibetan civil servants he met at the reception centers along the way—in Nepal and Delhi, and finally, upon arrival in Dharamsala—who were tasked with handling the documents, finances, and needs of the recently arrived Tibetans. From Dharamsala’s reception center, Tapsang was sent to Upper TCV, the main branch of the Tibetan Children’s Village residential school, where he would spend two years.

Image 05 and 06: Students forming the map of Tibet sometime in the 1970s (top). “Unity is Strength,” calisthenics performance at the founding anniversary of the Upper TCV in 2016 (bottom). Photo (top) courtesy of Sonam Tsering.

It was his time at Patlikul, another branch of TCV near Manali where Tapsang went after Upper TCV, that made the most profound impact on him. At Patlikul, he became a more serious student because of the small and intimate size of the school. Due to its remote location in the forested mountains, teachers and students lived in close proximity. Teachers were not simply teachers. They also took on the role of caring adults, neighbors, and adoptive parents. It was normal, according to Tapsang, for teachers to invite students to their homes to share meals with their families. Tapsang quickly took a liking to two teachers who guided and inspired him to become a good student. The first was a science teacher by the name of Gyen (teacher in Tibetan) Tashi. “Gyen Tashi was an inspiring teacher,” recalls Tapsang, “he always made class material interesting.” Gyen Tashi had a daily habit of reading newspapers, which Tapsang emulated. Tapsang also credits Gyen Tashi for instilling in him a love of reading English. The second teacher to make a profound impact on Tapsang was Gyen Ngawang Woeber, a Tibetan language teacher. Creative fiction writing was popular among students when Tapsang was in school. Gyen Ngawang took advantage of this trend by having students write tsom (short stories in Tibetan) as part of their coursework. This had the effect of inspiring a love of Tibetan literature and stories among students such as Tapsang. Tapsang has maintained a close relationship with Gyen Ngawang that has lasted well beyond school and into his adulthood.

Tapsang also developed close relationships with his fellow students. Tapsang said he sometimes felt lonely at the school, especially when his classmates born to families in exile brought stories of fun back from their holiday breaks. When I asked how he coped with such loneliness, Tapsang emphasized his friendships. Some were friends from Lhasa whom he had met at the reception center in Dharamsala, while others were classmates he met at school. They shared money, clothes, food, and all other resources. While reflecting on these relations, Tapsang said he realizes now that these friends were like family to him; Tapsang had one family in Tibet and this expanded network of kin in exile. By mobilizing idioms of kinship in this way, Tapsang reinforced the enduring quality and closeness of these relationships (Carsten 2019). This was not about replacing family with friends, but instead represented a way of adapting to the realities of being separated from kin in the face of continuing colonialism. Tapsang credits these strong friendships with keeping him from facing emotional problems in exile. Even though he and his friends are now adults living in different parts of the world, they continue to be in touch with one another. Many continue to send him money and clothes from afar. Their connections as family, not just as school friends, are now normative in the global Tibetan diaspora. Such friend-as-family connections trouble assumptions around “friend” and “family” as distinct, bounded, fixed, or natural categories.

Tapsang’s story demonstrates how strong bonds of affinity, solidarity, and care among and between students and teachers allowed novel forms of kinship to emerge within the schools. While many details of his story reflect the particular experiences of students belonging to the second generation, the kin-making relations described by Tapsang were common across all generations of students who attended Tibetan schools in exile. Alongside these bonds of kinship that took root in the schools, the curriculum also forged solidarity and belonging by emphasizing Tibet’s civilizational history—including the kings of Tibet and the founding of the Tibetan empire, the development of Buddhism in Tibet, and the emergence of a standardized Tibetan writing script—as well as the more recent history of China’s invasion and occupation. These teachings helped form political subjectivities and a shared sense of national identity among students. Stressing a common history as well as a shared struggle for freedom, kinship was reconfigured along national lines: Tibetans in exile, across the diaspora, and in Tibet were more than what Benedict Anderson (2006 [1983]) would call an “imagined community.” They became a family. In this way, Tibetan refugees maintained a government-in-exile not through territorial sovereignty but through the formation of subjects who felt a sense of national kinship and belonging, and in turn recognized the governing structure’s institutional and symbolic existence and power (McConnell 2016).

Refugees, Sovereignty, and Settler Colonialism

Despite—and in response to—the ongoing Chinese colonial occupation of Tibet, the Tibetan community in exile has asserted its sovereignty and reproduced itself through these new forms of kinship grounded in schools. Refugee-constructed institutions such as Tibetan residential schools built in exile serve as pathways to de facto sovereignty. Claims of sovereignty within the settler colonies of North America (Morgensen 2011a, 2011b) and Palestine (Wolfe 2006; Salamanca et al. 2012) are similar to—but not entirely the same as—Tibetan sovereignty, which takes form in exile in response to Chinese settler colonialism. Following the Chinese invasion, Tibetan nationalist statehood gained new features to prevent the dissolution of Tibetan biological and cultural life. As such, the Tibetan case has parallels to the development of Indigenous nationhood elsewhere (Smith 2013 [1999]; Sturm 2002; Dennison 2012), which also posits its existence against colonial destruction and towards indigenous continuities.

Image 07 and 08: His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama arriving (top) and conferring Avalokiteshvara (Boddhisatva of Compassion and patron Buddha of Tibet). Empowerment teaching to student and staff at Upper TCV on May 29, 2015 (bottom). Photos by Tenzin Choejor.

Tibetan leadership provided a home for orphaned children and pedagogically encouraged new kinship relations in the space of educational institutions. Both a personal narrative and a shared account of the second generation of students’ experiences, Tapsang’s story reveals in part how Tibetan governmental institutions in exile operationalized cultural notions of kinship based on a shared history of Tibet to produce not only institutions, but also subjects who began to imagine each other, greater Tibet, and the government as kin, thus producing Tibetan sovereignty. What stories such as Tapsang’s show is the hope of renewal and the force of community against colonial developments in people’s lives and in the decisions they make, including escaping to exile. Kinship and education in the Tibetan exile experience combine to activate claims for sovereignty while re/creating a national family in exile and inside Tibet. As such, this case highlights indigenous ingenuity in social organization during times of ongoing colonialisms (Barker ed. 2005). In so doing, it demonstrates an important framework of kinship and governance as an agentive avenue for refusing settler colonialism (Simpson 2014) and initating indigenous continuity and futurity.

References:

Anderson, Benedict. 2006 [1983]. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso Books.

Barker, Joanne, ed. 2005. Sovereignty Matters: Location of Contestation and Possibility in Indigenous Struggles for Self‐Determination. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Carsten, Janet. 2019. “The Stuff of Kinship.” In The Cambridge Handbook of Kinship, edited by Sandra Bamford, 133–50. Cambridge Handbooks in Anthropology. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Dalai Lama, His Holiness. 1991. Freedom in Exile: The Autobiography of the Dalai Lama. New York: Harper Collins.

Dennison, Jean. 2012. Colonial Entanglement: Constituting a Twenty-first-century Osage Nation. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

McConnell, Fiona. 2016. Rehearsing the State: The Political Practices of the Tibetan Government-in-Exile. Toronto: John Wiley and Sons.

Morgensen, Scott Lauria. 2011a. “The Biopolitics of Settler Colonialism: Right Here, Right Now.” Settler Colonial Studies 1(1): 52–76.

Morgensen, Scott Lauria. 2011b. Spaces Between Us: Queer Settler Colonialism and Indigenous Decolonization. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Riggs, Damien W., and Elizabeth Peel. 2016. Critical Kinship Studies: An Introduction to the Field. New York: Springer.

Salamanca, Omar Jabary, et al. 2012. “Past is Present: Settler colonialism in Palestine.” Settler Colonial Studies 2(1): 1-8.

Simpson, Audra. 2014. Mohawk Interruptus: Political Life Across the Borders of Settler States. Durham: Duke University Press.

Smith, Linda Thuhiwai. 2021 [1991]. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. London: Zed Books Ltd.

Wolfe, Patrick. 2006. “Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native.” Journal of Genocide Research 8(4): 387-409.

Cite as: Lokyitsang , Dawa. 2022. “Sovereignty in Settler Colonial Times: Kinship and Education in the Tibetan Exile Community” American Ethnologist website, 03 March 2022, https://americanethnologist.org/features/reflections/sovereignty-in-settler-colonial-times

Dawa Lokyitsang is a PhD candidate in anthropology at the University of Colorado, Boulder. Her work looks at the development of sovereignty by Tibetans in exile through the making of schools and subjects, both in response to and in spite of Chinese colonialism, and as an avenue for securing Tibetan continuity and futurity. As such, her scholarship sits at the intersection of empire, colonialism, and nationalism.