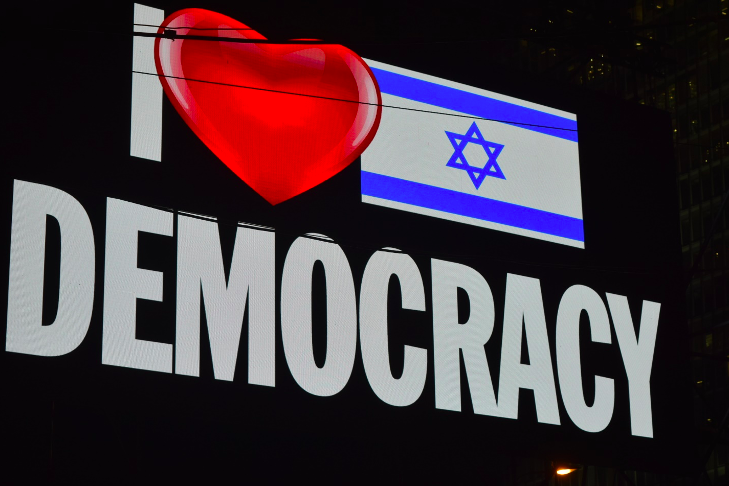

Massive screen at the main stage of the regular Saturday evening Israeli democracy demonstrations at Tel Aviv’s Kaplan Street from April 22, 2023, displaying a main message of the demonstrations using emojis. Photo by author.

At a posh hotel lobby overlooking Tel Aviv’s famed beaches, I had a chance encounter with Yoram (a pseudonym) in early April 2023. Yoram was at the hotel with other now-veteran protest organizers to try and disrupt a speech by Simcha Rothman, a member of Knesset from the most extremist of the ultra-nationalist and increasingly authoritarian Israeli parties that are now the government. Rothman is the chair of the Knesset’s powerful Committee on Constitution, Law, and Judiciary, and has been involved in re-thinking the Israeli judiciary for over a decade. Coming into power in January, Rothman and his coalition allies are attempting—with only one success so far—to pass a very comprehensive set of new laws that would give the sitting government much more power over such matters as selecting judges, as well as placing limits on the Supreme Court to over-ride the government. Opponents speak about the proposed changes as a “judicial overhaul” or “judicial coup” (supporters prefer “judicial reform”), even as the proposed laws—somewhere in the neighborhood of 150 and counting—go far beyond the judiciary, and will have far-reaching effects to claw back hard-won gains in gender rights, LGBTQ+ protections and, in other ways, further amplify the structural violence against Palestinians. It is this “judicial coup” and Rothman’s attempts to justify it in front of an international audience that Yoram and his group hoped to protest. News that Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu cancelled his participation at the event—the first time he would miss this international audience—felt like a victory to Yoram and the small band that had gathered at the hotel, who understood that Netanyahu was afraid to be have his speech disrupted. The government’s failure to pass the large majority of these laws is due in no small part to the well-organized, well-funded and wide-ranging coalition of protestors—to what we can call, after Holston (2008), a moment of democratic insurgency.

This particular democratic insurgency is mostly based on the mobilization of Israeli largely secular settler populations. Here I want to probe the limits of this settler mobilization, where “limits” means both boundary and potential. At the limits—and appearing as a yet unrealized potential to expand the democratic critique of the foundations of the Israeli state—is the fact that the very energy and sense of urgency in the protest movement is creating space for the small anti- or non-Zionist Israeli left to re-invigorate.

The very extreme positions of Rothman and other governing politicians are partially responsible for bringing together a broad opposing coalition for this insurgency. However, to date, this coalition notably does not include Palestinian protestors. In this short post, I will not be able to discuss the Palestinian activist-led events I attended and followed in 2023, nor speak about the Haifa protests, which have a different configuration.

A longer consideration would delve more into the inability of the majority of Israeli demonstrators to politically “speak together” with Palestinians (Bishara 2022). The current battle to (re-)gain hegemonic leadership over the state creates limits to the protests’ “expansive” potential (see Williams 1991) for greater democratic inclusion. Very briefly, as manyhave pointed out, the demonstrations mainly represent the message and analysis of the Ashkenazi business and intellectual elites from the greater Tel Aviv area (Gush Dan), and they are populated mostly (though not exclusively) by protestors from affiliated populations. Anthropologist Smadar Lavie has explained why marginalized Mizrahi Jewish citizens, especially those living in the economic peripheries, are not found in large numbers among the protestors, and, as she has previously detailed in her book (2018), why they have tended to support rightwing nationalism. Palestinian citizens of the state have explained in great detail why they feel that the messaging and purpose of the protests do not include their criticisms about on-going violent dispossession and exclusion. Historians trace this on-going structural violence to the foundational Zionist settler colonial project that emerged within the British imperial rule of Palestine (roughly 1918-1948) (for example, Khalidi 2019; Masalha 1992; Pappé 2007; Robinson 2013; Sabbagh-Khoury 2023). This historical analysis has become part of current citizen Palestinian political speech (Rouhana and Sabbagh-Khoury 2014).

As the small group of protestors and journalists waited for Rothman to arrive, Yoram told us several stories that point to the tensions in the protest movement. Yoram belongs to a powerful business leadership that is not able to win elections but still directs an important part of the economy, and also has a great deal of moral authority as military veterans. Yoram explained that he is a CEO of an Israeli high-tech start up, making him part of the Ashkenazi-dominated business elites of the greater Tel Aviv area that have emerged since the neoliberal reforms that started in the mid-1980s (Shafir and Peled 2002; Shalev 1997). Yoram told us that he is currently working “24/7” on protest, and he barely checks in with the manager of his company. “Just to make sure it’s still going.” Yoram is a poster boy for the supposed story of Israel as “start-up nation,” a term used to brand the country as global leader on innovation. (Critics have noted that this branding even in narrow terms is not backed up by the state’s own numbers, with one commenting acerbically that “start-up nation” sounds better than “large developer of weapons” or “a hotspot for [investment] speculators.”) Israeli reporting about the high-tech sector emphasizes its importance to the overall economy: claiming for instance that the sector currently accounts for some 50% of Israeli exports, 16% of GDP, and 25% of collected income tax. To hurt this sector is, the argument goes, to hurt the economy for everyone. Massive mediatized battles occur every time an international financial analyst, like Moody’s, mentions the judicial overhaul as a reason to divert investment away from Israeli companies.

Yoram is also associated with the group “Brothers and Sisters In Arms” (Akhim Leneshek), military reservists who are openly protesting the proposed new laws and have even threatened to withhold military service. His first story dealt with this group. With a wide grin, Yoram told us the story about group of veterans, Kippur Fighters, who earlier this year took a tank from a state commemoration site, having fought nearby in the 1973 war against Syria and Egypt. The idea was to use the tank as part of a protest convoy, until they were stopped by police. Yoram chuckled as he explained that a group of carpenters thought it would be better if they had a replica tank—one which they now bring to display at the Tel Aviv weekly protests. The veterans described by Yoram believed they could take the tank as part of their rights as full-fledged citizens. They represent a hallowed group in Israeli society, who according to most official versions about 1973, defended the state from a surprise attack during Yom Kippur and beat back the Arab armies.1

Wooden replica tank brought by 1973 Veterans group “Kippur Fighters” to Saturday evening Kaplan Street protests in Tel Aviv, from April 22, 2023. Replica scrolls of the Declaration of Independence hang in front on either side. The large Hebrew signs read “1973 Kippur Fighters fighting for the identity of the state.” Photo by author.

Yoram then told us a story about an impromptu protest that had occurred at the Jewish Federations of North America annual conference. Deciding they wanted to join the protests, a group of young participants left the conference venue. “So we brought them a bunch of veterans from Kippur Fighters, and these kids are really Zionist and they were excited to meet them [the veterans].” Yoram glowed as he recounted this success. The story both highlighted support from young Jewish Zionists abroad and the form of Zionism that this elite believes best represents Israeli politics: proud of its military history and liberal in Israeli terms. The absence of Palestinian citizens in demonstrations and Palestinian criticism of that history does not enter the conversation.

Yet there was one moment in the conversation with Yoram that exposed the limits to his way of thinking. He described the ongoing protests at Kaplan Street in Tel Aviv, which have taken place every Saturday evening, and which, to his eyes, represent the “spectrum” (keshet) of Israeli demonstrators. There are the different stations, he explained, by listing first different military units that line Kaplan Street: intelligence, air force, armored corps, and a few others. Yoram went on and mentioned civil society groups that line the main protests in Tel Aviv, like the Women Building an Alternative (Bonot Alternativa), who wear red shirts, and the Pink Front, who stage protests for equality and are especially associated with supporting LGTBQ+ communities. Each have their own “station” on the street, where they register supporters, give out stickers, sell protest paraphernalia (like T-shirts), and so on.

Some of the civil society “stations” at the weekly Saturday evening Kaplan Street protests in Tel Aviv. From right top: Women Building an Alternative (Bonot Alternativa), the Movement for Quality Government, and the Pink Front. Photos by author.

As Yoram surveyed the different stations, someone mentioned the Anti-Occupation Bloc, which meets at a specific corner every week, and which attracts some of the most anti-Zionist Jewish demonstrators and even a few Palestinian protestors. At the Anti-Occupation Bloc protests, mostly Jewish protestors wave Palestinian flags—at first with some police interference but now generally tolerated—and slogans include “Free Palestine” and “From the Jordan [River] to the [Mediterranean] sea, equality for everyone.” Many older anti-Zionists, who had not gone to protests in years, are now attending regularly and several commented that they had re-established contacts with old friends—the protests had become a regular social event as well as a site for renewing political comradery. On one Saturday evening protest, a group held up signs that spelled out the word “apartheid” in blue and white lettering as thousands streamed by holding Israeli flags. The coloring of the letters mimics and criticizes the blue and white of the Israeli flag that dominates the weekly demonstrations.2

Large sign marking the corner of the Anti-Occupation Bloc at the weekly Saturday evening protests in Tel Aviv, and blue and white “apartheid” letters brought to the protest on April 22, 2023 as other mainstream protestors stream by holding Israeli flags. Photos by author.

In other words, the Anti-Occupation Bloc absolutely does not embody the Zionism that Yoram saw in the young protestors from the North American federations or the veterans who bring a replica tank to the protests. I waited to see what Yoram would answer, wondering if he would sound off against what people in his position would generally call the radical left. He answered simply, “Yes, and the Anti-Occupation Bloc.” To my surprise, the Anti-Occupation Bloc, where for example, gather the supporters of Jewish youth refusing to serve in the Israeli military, are still part of Yoram’s spectrum.

In Israeli political terms, refusing to serve in the military because it is seen as an oppressive institution or describing the Israeli state as an apartheid state or calling for equality for all Israelis and Palestinians between the river and the sea are messages and mobilization associated with the (so-called) radical left. Or as some of its members call it, the “real left” to distinguish this political subjectivity from that of the Zionist left (associated with a call for compromise on territorial aspirations, like a two-state solution, where Israel and Palestine would be independent countries, and Israel would remain a Jewish state that privileges its Jewish citizens).

How can this Israeli settler insurgency tolerate the Bloc? The organizers of the Kaplan Street protests allow the Bloc its own station on Kaplan, but they are not highlighted among the main stage speakers, nor were they invited to the special “Independence Protest” (mekha’at atzma’ut) on Israeli Independence Day. There are clear limits to the tolerance, and the Bloc is not considered a central part of the protest movement by folks like Yoram. Yet there it is on Kaplan Street every week, and potentially growing—why? Part of an answer is shared networks. It would not be a surprise to find out that many on the radical left have family or close friends who work in high-tech or other affiliated businesses and bureaucracies that are largely staffed by Ashkenazi Israelis. This shared network is certainly true of my extended Israeli family, where anti-Zionists have close family and friends in the Ashkenazi-dominated elites.

Does the tolerance for the Anti-Occupation Bloc mean that a wider opening is possible, where more Israelis and especially Israeli organizations would begin to wrestle with the apartheid institutions of the state that systematically uphold Jewish settler supremacy and dispossess Palestinians? The current conditions suggest we are very far from such a wholesale questioning of Israeli settler colonial democracy. In a situation where a majority of Jewish-Israelis describe themselves as “rightwing,” (Scheindlin 2020) and a majority of Palestinians do not have the right to vote, and where there is as yet very little official pressure for change from the North Atlantic governments that support the Israeli state, the Israeli democratic crisis does currently have a limited horizon.

What, then, is meant by protestors like Yoram when they speak of democracy? What does the big banner sign, displayed at a Saturday evening protest, “I ❤️ 🇮🇱Democracy” (see above) mean? These protestors generally rationalize their opposition to the government’s proposed laws as: 1) a fight against Netanyahu’s attempt to maintain himself in power at all costs, including in alliance with extremist political Judaism in the form of religious Zionist and ultra-orthodox parties, and 2) a fight against his government’s actions that could potentially harm economic growth. On the first point, in other words, the coalition of protestors are positioning themselves as protectors of what the liberal sociologist TH Marshall (1950) famously called civil and political rights, especially of Jewish citizens. They are guarding against the governing parties open homophobia and racism for example, as well as the attempt to entrench more limits to the citizenship of Palestinians. On the second reason, the protestors position themselves as protectors of everyone’s social rights (Ibid.), as they consider themselves to be the real stewards of economic dynamism and of the Jewish democracy promised (according to them) in the Declaration of Independence.3

On the economy, the fears of the business elite like Yoram seem to stem from the possibility of losing the predictability of markets that are ensured by somewhat independent courts, as well as reporting systems like the Central Bureau of Statistics. Israeli democracy, then, is a liberal democracy in the following sense: market liberalism requires the stability of certain institutions for capitalist accumulation. Part of what is not generally seen by tech capitalists, as anthropologists Sophia Goodfriend and Matan Kaminer have noted for the Israeli case, is the important impact of state subsidies for arms manufacturing on the high-tech sector, and thus the close integration of high-tech with state militaries.

At the same time, another aspect seems to be at work. Bourgeois consciousness is not built around market logics alone. Political and civil rights—and the public life which comes about in protecting them—have taken on a life of their own and play an important role in the loose coherence of the protest movement. And here it is important to consider one prominent counter-image in protests: the ultra-orthodox parties in government, and somewhat by extension, the more extremist religious ultra-nationalists like Simcha Rothman. They instantiate a secular Israeli version of an anti-democratic bogey-man. A decades-long complaint of secular Israelis like Yoram has been that the ultra-orthodox in particular do not pull their weight, either economically or militarily. Ultra-orthodox men serve in the military in very small numbers, despite constant efforts to recruit them, and the ultra-orthodox parties are important to gaining state subsidies for youth in their communities to study in religious schools (yeshivas). Two of the main points made when protestors speak about democracy deal with freedom from “religious coercion” (kfiya datit) and from (so-called) “shirking military service” (hishtamtut). I would wager that the majority of protestors do not have social networks—family and close friends—that tie them to ultra-orthodox communities.

Opposing these religious parties, the public life that has arisen at the Tel Aviv-centric protests has given some space to Israeli anti-Zionism in the form of the Anti-Occupation Bloc. The Anti-Occupation Bloc is part of Yoram’s spectrum, even though the various groups in this Bloc promote a refusal of military service, and promote a political analysis that would require a re-constituting of the state. It remains to be seen how long this tolerance will stay intact, and to what extent the presence of the Anti-Occupation Bloc can expand the current Israeli debate about democracy between the river and the sea.

Notes

[1] The history of the wars between Israel and Arab countries from 1948 and 1973 is much more complicated than this official version, but outside of what can be covered here.

[2] The idea that the State of Israel is committing the crime of apartheid according to international law, among other violations, is now documented by several human rights NGOs like Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International. The apartheid analysis also has a longer history in the Palestinian national movement, going back to at least the 60s (Zreik 2004; Zreik and Dakwar 2020).

[3] On Marshall’s tripartite distinction of civil, political and social rights, see Holston 2008, 317.

References

Bishara, Amahl A. 2022. Crossing a Line: Laws, Violence, and Roadblocks to Palestinian Political Expression. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press.

Holston, James. 2008. Insurgent Citizenship: Disjunctions of Democracy and Modernity in Brazil. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Khalidi, Rashid. 2019. The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine: A History of Settler Colonialism and Resistance, 1917-2017. New York: Metropolitan Books.

Lavie, Smadar. 2018. Wrapped in the Flag of Israel: Mizrahi Single Mothers and Bureaucratic Torture. Revised Edition. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

Marshall, T. H. 1950. “Citizenship and Social Class.” In Citizenship and Social Class, and Other Essays., 1–83. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Masalha, Nur. 1992. Expulsion of the Palestinians: The Concept of “Transfer” in Zionist Political Thought, 1882-1948. Washington, D.C.: Institute for Palestine Studies.

Pappé, Ilan. 2007. The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine. Oxford: Oneworld.

Robinson, Shira. 2013. Citizen Strangers: Palestinians and the Birth of Israel’s Liberal Settler State. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Rouhana, Nadim N., and Areej Sabbagh-Khoury. 2014. “Settler-Colonial Citizenship: Conceptualizing the Relationship between Israel and Its Palestinian Citizens.” Settler Colonial Studies 5 (3): 1–21.

Sabbagh-Khoury, Areej. 2023. Colonizing Palestine: The Zionist Left and the Making of the Palestinian Nakba. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Shafir, Gershon, and Yoav Peled. 2002. Being Israeli: The Dynamics of Multiple Citizenship. Cambridge Middle East Studies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Shalev, Michael. 1997. “Zionism and Liberalization: Change and Continuity in Israel’s Political Economy.” Humboldt Journal of Social Relations 23 (1/2): 219–60.

Scheindlin, Dahlia. 2020. “Has the Israeli Right Peaked?” Foreign Policy. February 14, 2020. https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/02/14/has-netanyahu-likud-israeli-right-peaked/.

Weiss, Erica. 2014. Conscientious Objectors in Israel: Citizenship, Sacrifice, Trials of Fealty. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Williams, Brackette F. 1991. Stains on My Name, War in My Veins: Guyana and the Politics of Struggle. Durham: Duke University Press.

Zreik, Raef. 2004. “Palestine, Apartheid, and the Rights Discourse.” Journal of Palestine Studies 34 (1): 68–80.

Zreik, Raef, and Azar Dakwar. 2020. “What’s in the Apartheid Analogy? Palestine/Israel Refracted.” Theory & Event 23 (3): 664–705.

Alejandro I. Paz is an Associate Professor of Anthropology at the University of Toronto Scarborough, and he has written about the politics of migration, language and citizenship in Israel/Palestine, as well as settlement in occupied East Jerusalem. His book Latinos in Israel: Language and Unexpected Citizenship (Indiana UP) was published in 2018. His current research is about Israeli English online journalism, and its impact on North Atlantic public opinion.

Cite As: Paz, Alejandro I. 2023. “Notes on the limits of Israeli settler democratic insurgency”, American Ethnologist Website, 31 July 2023, [https://americanethnologist.org/online-content/essays/notes-on-the-limits-of-israeli-settler-democratic-insurgency/]