What does the daily practice of writing fieldnotes look and feel like to ethnographers? What do fieldnotes actually look like, and how are they best written and organized? Why, for some of us, do they feel especially burdensome when investigating a sensitive topic? How do fieldnotes convey the emotional journey of fieldwork? Can the ephemerality of technology support them and, if it does, what do we do with them afterwards? How has the experience of writing or looking back on fieldnotes changed during the COVID-19 pandemic? What are the social dynamics and contours of writing and reading fieldnotes in this particular political moment?We the editors, Magdalena Zegarra Chiappori and Verónica Sousa, are in different phases of our PhD programs. Magdalena is currently writing her dissertation and is thus engaged in the process of looking back on her fieldnotes. Verónica is doing fieldwork, writing fieldnotes on a daily basis. Our experiences taking and reviewing our fieldnotes have been fraught with uncertainty and frustration, but have also inspired curiosity and creativity, providing for us the space and freedom to write in unconventional ways. For Magdalena, fieldwork and note-taking were ambivalent experiences: while she often found herself powerless in the face of her interlocutors’ everyday struggles, she also discovered in ethnographic writing a political engagement with her elderly Peruvian interlocutors. Verónica, for her part, has struggled with the emotional energy required for the practice of note-taking after a long day of fieldwork. Voice notes have saved her many times, as her in-depth notes can take several hours to write. Fieldnotes have forced her to question her memories and perceptions of social life, which has in turn led her to critique her own practice as an anthropologist and the field as a whole. This has led her to approach ethnography as a purposeful and political act of care, in addition to making her a stronger writer. These reflections, as well as our many conversations, have led us to some illuminating insights about our own efforts, not to mention a great appreciation for the excellent ethnographies we have encountered along the way. And of this, we took note.

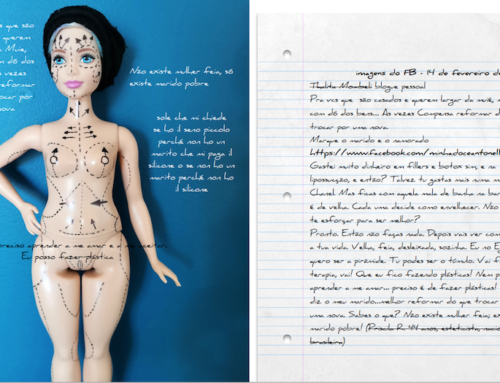

The essays in this collection seek to address how our oftentimes disordered, fragmentary, or messy fieldnotes can be, precisely, raw matter for the production of more radical and compassionate ethnographies. Pivotal to the anthropological enterprise, yet so often indecipherable, incomplete, and disordered (Jackson 1990:13), fieldnotes are for ethnographers a space for reflection, a methodological exercise, and a creative endeavor. Our writing of them is sometimes exhausting, sometimes rewarding; they might be experienced as tedious, playful, constricting, painful, unfinished, or impossible. In our fieldnotes, we not only dive deeply into a social universe that is in some ways unintelligible to us—at least, at the beginning—but we also explore the depths of our vulnerability as individuals who carry out research. As Vincent Crapanzano (1977) notes, writing ethnography—and fieldnotes are part of this—is an act of self-constitution, creation, and confrontation with an other that calls us to question what we know about the world and our own selves. In that sense, writing fieldnotes can offer profound insights, but it can also be messy, confusing, and chaotic. Robert Emerson, Rachel Fretz, and Linda Shaw have aptly stated that fieldnotes are not polished, articulated, and organized texts but, rather, the “smaller, less coherent bits and pieces of writings” that provide foundations for the development of comprehensive ethnographies (1995, vii). The ethnographer writes, says Clifford Geertz (1973, 19), but writing “extends before, after, and outside the experience of empirical research” (Clifford 1990, 64). Fieldnotes are, indisputably, the initial part of the process of writing. They are foundational to the practice of ethnography as method and as form.

This collection reflects upon the challenging emotional and intellectual labor of writing ethnographic fieldnotes and attempts to grasp the complexities and ambiguities of the process. It also considers the materiality of the notes themselves. It is a collective attempt to grapple with the emotional, political, personal, and methodological challenges of writing fieldnotes, especially in these fraught times of COVID-19, widespread political and social unrest, socioeconomic turmoil, and war. It includes the reflections, ideas, and thoughts that several anthropologists across the world (who work on different topics) have had on the arduous experience of note-taking. As Geoffroy Carpier explains, fieldnotes usually reflect the wavering beginnings of research itineraries. However, these beginnings are not exempt from doubt and questioning. Miryam Nacimento and Laís Gomes Duarte accurately affirm that, in graduate school, one is often not given advice on the intricacies of note-taking, and learning how to do it is a lonely discovery. Undoubtedly, note-taking requires effort and, as Amelia Frank-Vitale states, it can frequently force us to overcome the ever-infamous writer’s block. Silence, however, does not only reflect the impossibility of the ethnographer to find a method to capture the social dynamics around her. As Daena Funahashi considers, silence can sometimes test what can be captured as note, or what can be said or articulated, while also problematizing what the “field” actually is. This is an arduous ethnographic journey. Michael Jackson writes about this beautifully when he reflects on how his first attempts of writing fieldnotes were filled with paucity, confusion, and superficiality; only with time did they end up encapsulating the critical events that determined his philosophical preoccupations. As Kamal Kariem writes, fieldnotes can be a space to “push forward, a testament that possibility remains,” especially amidst this critical global sociopolitical moment. Immersed in this time of economic, political, and social uncertainty, the anthropologist must find her own voice. Meryleen Mena does this by choosing to write about a moment of danger in the field as an unsettling experience, and to consider this political and anthropological moment through Black Diasporic feminist thought and community. Chiara Pussetti also achieves this by engaging with technologies that allow the ethnographer to transcend pen and paper, instead embracing voice messages, drawings, and pictures via art-based ethnography. These are ways of writing fieldnotes otherwise. Yet, technologies to record social life, as Janelle Taylor affirms, are always ephemeral and forever keeping record is only a fantasy. What are the limits and possibilities, then, of note-taking? And of the anthropological project more generally?We present to you the latest AES collection: Taking Note. We hope that these essays inspire critical thought and reflection for our readers, and motivate those who are in the field struggling with the daily exercise of putting into words their heavy ethnographic experiences. At a crucial social and political moment that is bringing change to the structures of power that shape our world, we aspire to provide anthropologists with an opportunity to reflect upon the intimacies of note-taking as well as the foundational role fieldnotes play within and beyond our discipline.

References

Clifford, James. 1990. “Notes on (Field)notes.” In Fieldnotes: The Makings of Anthropology. Edited by Roger Sanjek. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Crapanzano, Vincent. 1977. “On the Writing of Ethnography.” Dialectical Anthropology 2 (1): 69-73.

Emerson, Robert. M., Rachel. I. Fretz, and Linda L. Shaw. 2011. Writing Ethnographic Fieldnotes. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Geertz, Clifford. 1973. The Interpretation of Cultures. New York: Basic Books.

Jackson, Jean E. 1990. “‘Deja Entendu’: The Liminal Qualities of Anthropological Fieldnotes.”Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 19 (1): 8-43.

Magdalena Zegarra Chiappori is a PhD candidate in Anthropology at The University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. Her work is located at the intersections of old age, care, and precarity.

Verónica Sousa is a PhD candidate in Anthropology at the Institute of Social Sciences, University of Lisbon. Her work investigates the negotiations of harm and care in Catholic elder care centers in Lisbon, with a particular focus on the politics, social dynamics, and technologies of touch during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Cite As: Zegarra Chiappori, Magdalena, and Verónica Sousa. 2022. “Introduction” In “Taking Note: Complexities and Ambiguities in Writing Ethnographic Fieldnotes,” edited by Magdalena Zegarra Chiappori and Verónica Sousa, American Ethnologist website, 26 August 2022, [https://americanethnologist.org/features/collections/taking-note-complexities-and-ambiguities-in-writing-ethnographic-fieldnotes/introduction]