“Don’t you ever, ever feel, like you’re less than fuckin’ perfect.”

(Fuckin’ Perfect, Pink)

The fieldnotes I have chosen to reflect on come from fieldwork I carried out in Lisbon, Portugal between 2020-2022. The purpose of this fieldwork was to investigate “beauty work” and anti-aging practices during the COVID-19 pandemic among white middle-class women from 40 to 70 years old. The global sanitary emergency confronts us with what Ulrich Beck has called “metamorphosis of the world” (2017, 5): a radical life change that forces us to completely reconfigure our everyday routines at every level, including our beauty habits and even our modes of bodily self-perception. The transformation of everyday activities brought about by COVID-19 has altered experiences, perceptions, and understandings of the gendered body. The pandemic curtailed the possibility of going freely to the spa or to the hairdresser, to the gym, or to the beauty parlor . Many of the locations, which represent and shape the “beauty work” of the gendered body (Biggeri 2020; Manley 2020; Nussbaum 2011) were temporarily closed, while other self-care practices have become more central. My fieldwork was supported by the project EXCEL (The Pursuit of Excellence: Biotechnologies, Enhancement and Body Capital in Portugal),1 which focuses on the relationship between the 2008 financial crisis in Portugal and the increasing investment in aesthetic practices during and after the years of the recession.

While I was working on how this first crisis affected the consumption of cosmetic products and aesthetic procedures in Portugal, another crisis emerged: the COVID-19 pandemic. I wondered what might be the outcome of this new social, economic, and political calamity. To grasp its effects, I pursued a multimethod research strategy, which employed netnography, art-based ethnography (Pussetti 2018) and in-depth ethnography. I used netnography research methods (Kozinets 2010), and I likewise participated in different virtual social spheres such as e-groups, chat rooms, and online forums dedicated to beauty and self-care. Moreover, several offline and private practices have a clear correspondence online (and vice versa) and during lockdown, e-communities were vital for developing and maintaining important social ties between users, forming a system of relationships similar to ties of friendship.

I have also adopted self-ethnography and the multisensory methods of “art-based ethnography,” especially designed for the bodily, emotional, and sensorial aspects of this project. I employ photography as a medium for fieldnotes, as well as drawings on the body (my own body, the body of my “body entrepreneurs”2, and the plastic body of a Barbie doll3). I incorporate photographs in my fieldnotes as an opportunity to observe my own body through the medical gaze, examining the ways in which practitioners inscribe their expert knowledge on patients’ bodies and stigmatize visible signs of aging—such as wrinkles, sagging, or gray hair—as problems to be fixed, repaired, solved. Beauty is a question of image in a society obsessed with idealized body types. Our appearance—size, skin or hair color, height, and so on—is intimately connected to our identity as people. Via personal notes, voicemail messages to myself, and selfies, I illustrated a cosmetic surgeon’s authority over defining and shaping my body in the light of the mirage that is the ideal, hegemonic, and erotic female body of the capitalist market. In front of the medical gaze, my body presented itself as a blank and malleable canvas upon which surgeons could draw the ideal feminine form – carving the flesh, cutting the excesses, and redefining the lines—just as the sculptor shapes their marble. My body provided the canvas or clay for the artist’s masterpiece.

Through an approach that combines art and written anthropological narratives, I have tried to convey the emotional journey of my fieldwork and to reproduce the impacts of these beauty standards upon my own process of self-construction, balancing between what the others see and think of me, and what I began to desire. This bodily canvas represents the stories I collected in the field, the confessions of my friends and colleagues, and my own reflections and anxiety about my appearance. A combination of photos, fieldnotes, and collage helped me to offer visual insight into what I, as the researcher, have understood and felt during the process, with the goal of bringing the viewer to participate in the experience of the social actors involved.

The actual fieldwork relied on classical in-depth ethnography: participant observation, and informal and semi-structured interviews. Occasionally accompanied by a student research assistant, I carried out participant observation in private aesthetic clinics, where I interviewed thirty-three women and accompanied them in their aesthetic transformations during the lockdown periods. I formally interviewed the participants using an open-ended interview script, and spent some time with them engaging in informal conversations and observations in various settings, including hairdressers and beauticians. Interview questions explored a range of issues related to experiences of aging and losing precious time during the lockdowns, feelings about changes in bodies and appearance due to the restriction of staying at home, values surrounding beauty and youth, thoughts about whether they believed beauty and aging are under their control, aspirations and fears regarding the post-lockdown prospect of increased competition in all spheres of social life, their visions of successful self-care, and the beauty strategies they adopted to survive confinement.

My fieldnotes were taken on my tablet and smartphone, by voice, talking to myself about my own aging process, and recording the conversations with the women who were generous enough to share their experiences with me. Due to public health concerns, I had to remotely interview, by telephone or by Zoom, Google Meet, Teams, or Skype, some of my informants (12 beauty professionals, 4 health-care professionals and 2 investors who opened new cosmetic clinics in Lisbon during the pandemic in response to increasing demands from the public and clients). The interviews were audio recorded, transcribed, and analyzed to uncover recurring as well as unique or divergent themes and ideas.

By participating as an ethnographer in all arenas of the beauty market, constantly confronted with hegemonic discourses on youth and beauty, I became increasingly attentive and permeable to the ways my interlocutors in the field commented on my appearance. In every interview taking place in aesthetic and cosmetic medicine clinics, the professionals held up a mirror in front of my face, directing my attention to the imperfections of my skin texture, the enlarged pores, the lack of youthful radiance and glow, the expression wrinkles: the marionette, the bar code, the crow’s foot. Gradually, I came closer to my subjects’ perspectives, seeing my body through their lenses. I went from observer to observed, and began to incorporate a medical view that pathologized the signs of my aging.

To take my experience seriously means understanding the reality of a looks-based culture, exposing the entangled relationship between physical attractiveness, youth, femininity, women’s social status, and interactional power with all the psychological, social, and economic consequences involved. The photographic self-ethnographic narrative of the incorporation of hegemonic beauty norms and the desire for eternal youth, based on my experience as a medical cosmetic patient and in dialogue with other women “over-fifty,” turned out to be a significant lens to reflect on the intimate and personal ways that we incorporate contradictory socio-cultural expectations about how our body should be.

My fieldnotes are both a banal part of qualitative research and a deeply private and elusive kind of document. When reporting my fieldnotes in an article or books’ chapter, I quote them in their highly-polished, mediated, and edited appearance. Rather than expose what fieldnotes actually look like, this practice tends to obscure my personal memories and reflections, my doubts, and the most emotional elements. All of my interviews were recorded and transcribed in Portuguese. My own autobiographical reflections are in Italian, Portuguese, or English (usually, my emotional memories are in Italian, the factual daily experiences in Portuguese, and the theoretical observations in English). As my fieldnotes are recorded on my phone or directly on photographs or a tablet, I will transcribe fragments of the dialogue, together with both the images taken in the field and my own reflections, and I will include the translation in English.4

Fieldnotes – Images and Text

Editors’ note: Below are the author’s images and text in the form of transcriptions and translations—as they had been written originally. We, the editors, have decided to publish them in their original form as an example of what we argue in this collection: that fieldnotes can be messy and imperfect, and it is crucial to demystify them.

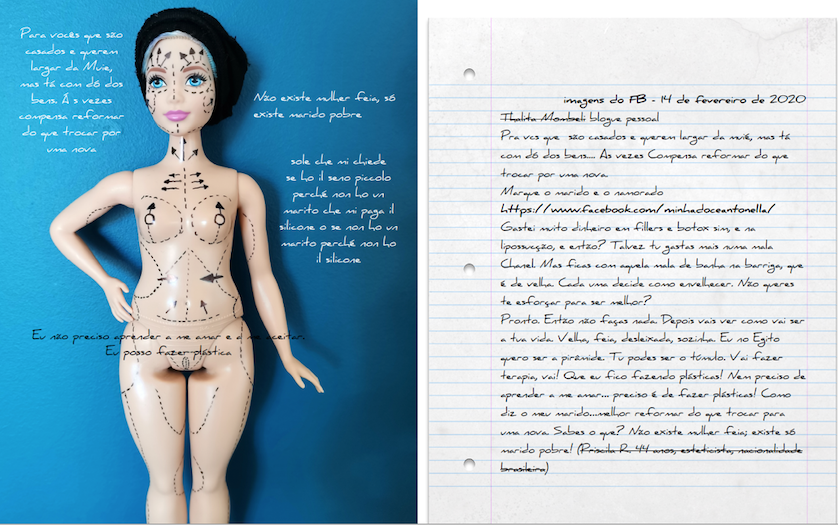

Marked up Barbie doll with Portuguese description on the left side. Portuguese writing on lined paper on the right side.

IMAGE: For those of you who are married and want to let go of the wifey, but are worried about your assets. Sometimes it pays off to refurbish [rather] than to trade for a new one. There is no ugly woman, there is only poor husband. Sole asks me if I have small breasts because I don’t have a husband who pays me for silicone or a husband because I don’t have silicone. I don’t need to learn to love and accept myself. I can do plastic surgery.

TEXT: FB images – February 14, 2020 Thalita Mombeli personal blog For those of you who are married and want to let go of the wifey, but are worried about your assets. Sometimes it pays off to refurbish [rather] than to trade for a new one. Tag your husband and boyfriend here. Yes, I spent a lot of money on fillers and botox, and liposuction, so what? Maybe you spend more on a Chanel bag. But you get that bag of lard on your belly, which is an old woman’s [belly]. Each person decides how to grow old. You don’t want to strive to be better? You don’t want to make an effort to be better? Then don’t do anything. Then you’ll see what your life will be like. Old, ugly, sloppy, alone. I want to be the pyramid in Egypt. You can be the tomb. Will do therapy, go! That I keep doing plastic surgery! I don’t even need to learn to love myself… what I need is plastic surgery! Like says my husband…better reform than switch to one new. Know what? There is no such thing as an ugly woman; there is only poor husband! (Priscila R. 44 years old, beautician, nationality brazilian).

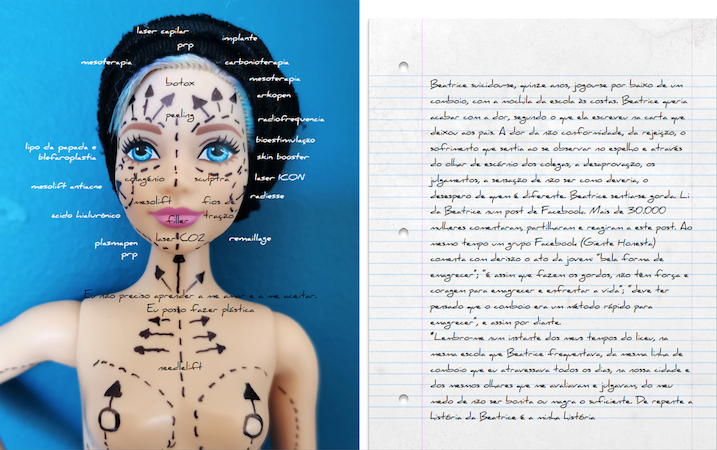

On the left side: Close-up of a marked up Barbie doll with Portuguese description. On the right side: Portuguese writing on lined paper.

IMAGE: I don’t need to learn to love and accept myself. I can have plastic surgery. capillary laser implant carbon therapy prp botox peeling mesotherapy arkopen radio frequency biosimulation skin booster ICON laser radiesse mailing mesotherapy chin liposuction blepharoplasty anti-acne mesolift hyaluronic acid plasmapen prp.

TEXT: Beatrice committed suicide, fifteen years old, threw herself under a train, with the school bag on her back. Beatrice wanted finish to feel the pain, according to what she wrote in the letter that she left it to her parents. The pain of non-compliance, rejection, the suffering she felt when looking at herself in the mirror and through from the mocking look of colleagues, the disapproval, the judgments, the feeling of not being as it should be, the despair of someone who is different. Beatrice felt fat – read from Beatrice in a Facebook post. More than 30,000 women commented, shared and reacted to this post. To at the same time a Facebook group (Honest Giente) comments with derision the young woman’s act: “beautiful way of lose weight”; “that’s how fat people do, they don’t have the strength and courage to lose weight and face life”; “must have thought the train was a quick method to slim down”, and so on. I remember in a moment from my high school days, at same school that Beatrice attended, from the same line of train that I used to cross every day, in our city and from the same looks that evaluated and judged me, from my afraid of not being pretty or thin enough. suddenly the Beatrice’s story is my story.*

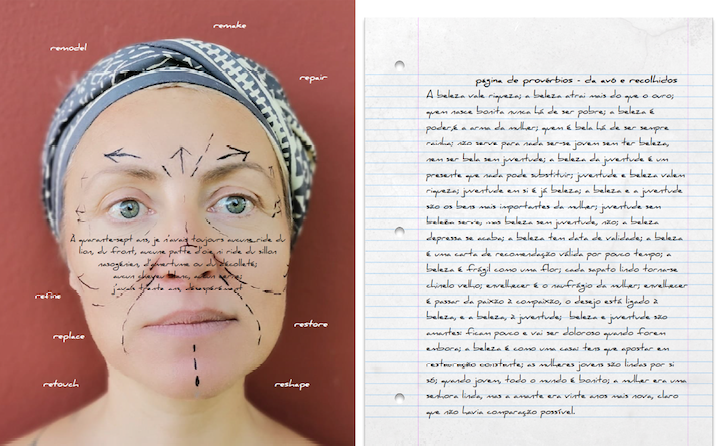

One the left side: Close-up of author’s face, marked up, with inscription in French and surrounded by the following English words: “remodel; remake; repair; restore; reshape; retouch; replace; refine.” On the right side: Portuguese writing on lined paper.

IMAGE: À quarante-sept ans, je n’avais toujours, aucune ride du lion, du front, aucune patte d’oie ni ride du sillon nasogénien, d’amertume ou du décolleté; aucun cheveu blanc, aucun cerne; j’avais trente ans, désespérément, remodel remake repair refine replace retouch restore reshape. English translation: At forty-seven, I still had no frown lines, no forehead wrinkles, no crow’s feet, no nasolabial folds, no bitterness wrinkles, no white hair, no dark circles; I was thirty years old, desperately, remodel remake repair refine replace retouch restore reshape.

TEXT: “beauty attracts more than gold”, “she who is born beautiful will never be poor”, “beauty is power”, “it is a woman’s weapon” “she who is beautiful will always be queen”; “it’s no good being young without beauty, nor beautiful without youth”. “youth and beauty are worth riches”; “youth in itself is already beauty”; “beauty and youth are a woman’s most important assets”; “youth without beauty is fine, but beauty without youth is not”; “beauty soon runs out”; “beauty has an expiry date”; “beauty is a recommendation letter valid for a short time”; “beauty is fragile like a flower: it is born and quickly dies”; “every beautiful shoe becomes an old slipper”; “growing old is a woman’s shipwreck”; “to grow old is to pass from passion to compassion”, “desire is linked to beauty, and beauty, to youth”; “beauty and youth are lovers: they stay a little and it will be painful when they go away”; “beauty is like a house: you have to bet on constant restoration”; “young women are beautiful by themselves”; “when young, everyone is beautiful”; “the woman was a beautiful lady, but her lover was twenty years younger, of course there was no comparison possible”.

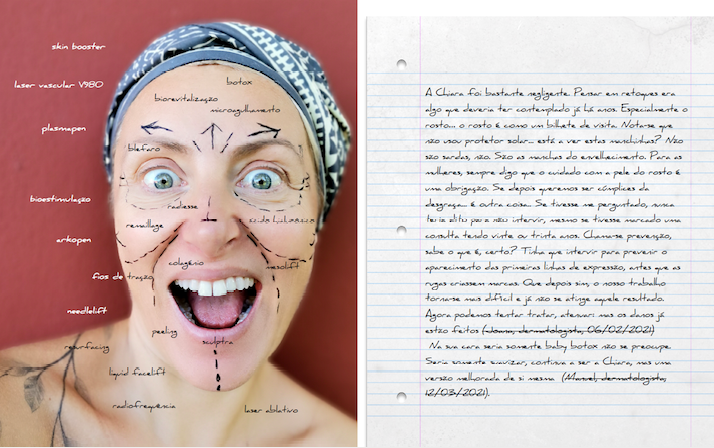

On the left side: Close-up of author’s smiling face, marked up, with names of medical procedures and terminology in Portuguese. On the right side: Portuguese writing on lined paper.

IMAGE: skin booster V980 vascular laser plasmapen biostimulation arkopen pull wires needlelift resurfacing liquid facelift readiofrequency botox biorevitalization microneedling blepharoplasty radiesse hyaluronic acid mesolift mailing collagen pull wires peeling sculptor ablative laser

TEXT: Chiara, you were rather negligent. Thinking about retouching was something you should have contemplated years ago. Especially the face… the face is like a calling card. You can tell you haven’t used sunscreen… see these little spots? They’re not freckles, no. They’re ageing spots. For women, I always say that caring for the facial skin is an obligation. If we then want to be accomplices of the disgrace… that’s something else! (Paul, dermatologist).

If you had asked me, I would never have told you not to intervene, even if you had made an appointment at twenty or thirty years old. It’s called prevention, you know what it is, right? You should have intervened to prevent the appearance of the first expression lines, before wrinkles create marks. And then, yes, our work becomes more difficult and we no longer achieve that result. Now we can try to treat, to attenuate: but the damage is already done (Joana, dermatologist).

On your face it would just be baby botox, don’t worry, or a biorevitalisation. It could even be something very soft like micro-needling. Nothing invasive. It would just be softening, you’re still Chiara, but an improved version of yourself. (Manuel, dermatologist).

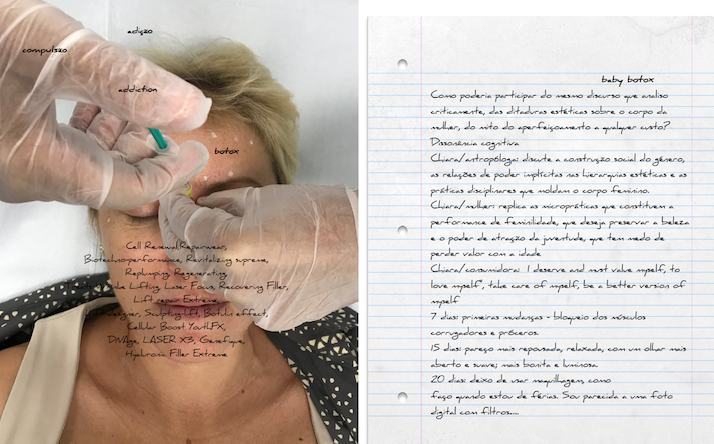

On the left side: Close-up of author receiving facial Botox injections in a clinic, with Portuguese and English terms and wording. On the right side: Portuguese writing on lined paper.

IMAGE: Cell Renewal, Repairwear, Biotechno-performance, Revitalizing supreme, Replumping, Regenerating, Treats Wrinke Lifting, Laser Focus, Recovering Filler, Lift repair Extreme, Lift-designer, Sculpting-lift, Botulin effect, Cellular Boost YouthFX, DNAge, LASER X3, Genefique, Hyaluronic Filler Extreme COmpulsion Addiction botox

TEXT: How could I participate in the same discourse that I critically analyse, that of the aesthetic dictatorships over women’s bodies, the myth of perfection at any cost?

“cognitive dissonance” Chiara/anthropologist discusses the social construction of gender, the power relations implicit in aesthetic hierarchies, and the disciplinary practices that shape the female body. Chiara/woman I deserve and must value myself, to love myself”, take care of myself, be a better version of myself. 7 days: first changes—muscle blockage corrugators and proceros. 15 days: I look more rested, relaxed, with a longer look open and smooth; more beautiful and luminous. 20 days: I stop using makeup, as I do it when I’m on vacation. I look like a photo with filters…

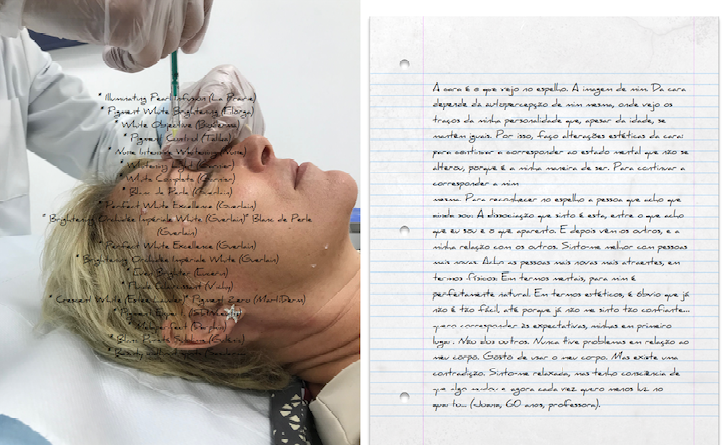

On the left side: Close-up of author receiving facial Botox injections in a clinic from profile, with English and French language products and branding. On the right side: Portuguese writing on lined paper.

IMAGE: Illuminating Pearl Infusion (La Prairie) Pigment White Brightening (Filorga) White Objective (Bioderma) Pigment Control (Talika) Nuxe Intensive Whitening (Nuxe) Whitening Light (Garnier) White Complete (Garnier) Blanc de Perle (Guerlain) Perfect White Excellence (Guerlain) Brightening Orchidée Impériale White (Guerlain) Blanc de Perle (Guerlain) Perfect White Excellence (Guerlain) Brightening Orchidée Impériale White (Guerlain) Even Brighter (Eucerin) Fluide Éclaircissant (Vichy) Crescent White (Estee Lauder) Pigment Zero (MartiDerm) Pigment Expert. (ISDINceutis) Melaperfect (Darphin) Blanc Pureté Sublime (Galénic) * Beauty without spots (Sesderma)

TEXT: The face is what I see in the mirror. My self image. My self-perception of myself depends on the face, where I see the traits of my personality that, despite age, remain the same. That’s why I make aesthetic changes to my face: to continue to correspond to the mental state that hasn’t changed, because it’s my way of being. To continue to correspond to myself. To recognise in the mirror the person I think I still am. The dissociation I feel is this, between what I think I am and what I appear. And then come others, and my relationship with others. I feel better with younger people. I find younger people more attractive, physically speaking. In mental terms, for me it is perfectly natural. In aesthetic terms, it’s obviously not so easy, not least because I no longer feel so confident… I want to meet expectations, mine in the first place. Not other people’s. I’ve never had any problems with my body. I like using my body. But there is a contradiction. I feel relaxed, but I am aware that something has changed and now I want less and less light in the bedroom… (Joana, 60 years old, teacher).

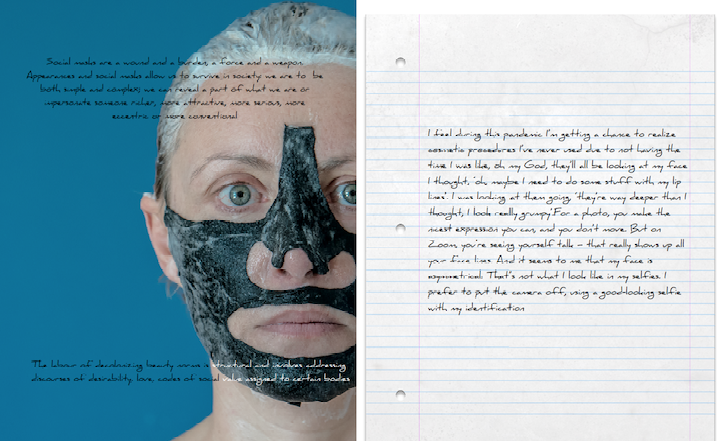

On the left side: Author’s face with black skin mask and blonde hair pulled back (cut off); also featuring writing in English. On the right side: English writing on lined paper.

IMAGE: Social masks are a wound and a burden, a force and a weapon. Appearances and social masks allow us to survive in society: we are to be both simple and complex; we can reveal a part of what we are or impersonate someone richer, more attractive, more serious, more eccentric or more conventional. The labour of decolonizing beauty norms is structural and involves addressing discourses of desirability, love, codes of social value assigned to certain bodies.

TEXT: I feel during this pandemic I’m getting a chance to realize cosmetic procedures I’ve never used due to not having the time I was like, oh my God, they’ll all be looking at my face I thought, ‘oh, maybe I need to do some stuff with my lip lines’. I was looking at them going, ‘they’re way deeper than I thought, I look really grumpy’. For a photo, you make the nicest expression you can, and you don’t move. But on Zoom, you’re seeing yourself talk—that really shows up all your face lines. And it seems to me that my face is asymmetrical. That’s not what I look like in my selfies. I prefer to put the camera off, using a good-looking selfie with my identification.

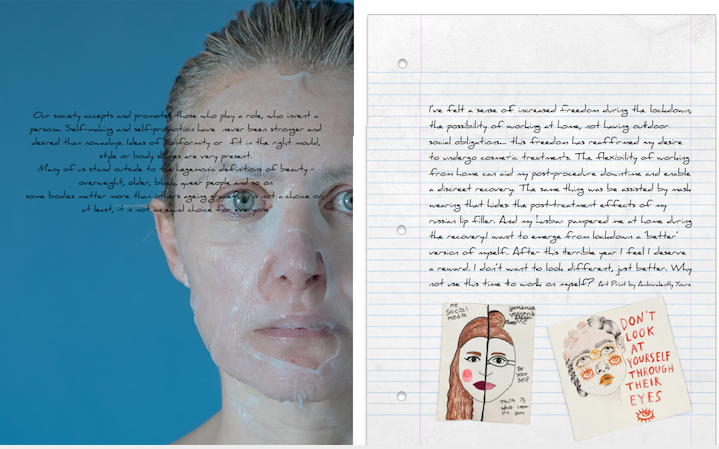

On the left side: Author’s face with translucent skin mask and blonde hair pulled back (cut off); also featuring writing in English. On the right side: English writing on lined paper with two art prints in color along the bottom.

IMAGE: Our society accepts and promotes those who play a role, who invent a persona. Self-making and self-promotion have never been stronger and desired than nowadays. Ideas of conformity or fit in the right mould, style or body shapes are very present. Many of us stand outside to the hegemonic definitions of beauty—overweight, older, black, queer people and so on some bodies matter more than others ageing gracefully is not a choice or, at least, it is not an equal choice for everyone.

TEXT: I’ve felt a sense of increased freedom during the lockdown, the possibility of working at home, not having outdoor social obligations… this freedom has reaffirmed my desire to undergo cosmetic treatments. The flexibility of working from home can aid my post-procedure downtime and enable a discreet recovery. The same thing was be assisted by mask wearing that hides the post-treatment effects of my russian lip filler. And my husban pampered me at home during the recovery. I want to emerge from lockdown a ‘better’ version of myself. After this terrible year I feel I deserve a reward. I don’t want to look different, just better. Why not use this time to work on myself? Art Print by Ambivalently Yours.

Notes

[1] The EXCEL project is funded by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT), under the grant agreement PTDC/SOC-ANT/30572/2017. The grant is managed by the Institute of Social Sciences at the University of Lisbon, under my coordination as Principal Investigator. Prompted by economic analyses of the increase in consumption of cosmetic interventions in Portugal after the global financial crisis, EXCEL sheds new light on the relation between people’s own ideals, desires, and aspirations of aesthetic perfection and bio-investment practices to promote personal competitiveness.

[2] This is a term I use for my interlocutors who strategically improve their own appearance to increase their social, cultural, and economic power, as well as the chances of professional success and in love relationships.

[3] I have produced some “hacked Barbies,” reproducing my own corporality and body interventions on the doll during the workshop The Hacked Barbie, born as a dissemination activity of the project EXCEL, organized by Federica Manfredi and myself, and presented for the first time at the World Anthropology Day 2021, organized by the University Milan-Bicocca. The phenomenal experience motivated forthcoming editions in virtual Portugal, Italy, and Brazil.

[4] Some of the fieldnotes appear in a published work: Pussetti, C. 2021. “Because You’re Worth It! The Medicalization and Moralization of Aesthetics in Aging Women.” Societies 11(3): 97. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc11030097

References

Beck, Ulrich. 2017. The Metamorphosis of the World: How Climate Change is Transforming Our Concept of the World. Malden: Polity Press.

Berkowitz, Dana. 2017. Botox Nation Changing the Face of America. New York: New York University Press.

Biggeri Mario. 2020. “Introduction: Capabilities and Covid-19.” Journal of Human Development and Capabilities 21(3): 277-279.

Cameron, Erin, et al. 2019. “The female aging body: A systematic review of female perspectives on aging, health, and body image.” Journal of Women & Aging, 31(1): 3-17.

Emerson, Robert. M., Rachel. I. Fretz, and Linda L. Shaw. 2011. Writing Ethnographic Fieldnotes. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Gimlin, Debra. 2002. Body Work: Beauty and Self-image in American Culture. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Kaminski, Patricia L., et al. 2005. “Body Image, Eating Behaviors, and Attitudes toward Exercise among Gay and Straight Men.” Eating Behaviors 6(3): 179–187.

Kozinets, Robert V. 2010. Netnography: The Marketer’s Secret Weapon. How Social Media Understanding Drives Innovation. New York: NetBase.

Manley, Rhys. 2020. “Light at the End of the Tunnel: The Capability Approach in the Aftermath of Covid-19”. Journal of Human Development and Capabilities 21(3): 287-292.

Nussbaum, Martha. 2011. Creating Capabilities: The Human Development Approach. Harvard: Harvard University Press.

Peplau Letitia Anne, et al. 2009. “Body Image Satisfaction in Heterosexual, Gay, and Lesbian Adults.” Archives of Sexual Behavior 38(5): 713–725.

Pussetti, Chiara. 2018. “Art-Based Ethnography. Experimental Practices of Fieldwork”. Special Issue of Visual Ethnography. 7(1): 1-13.

Sanjek, Roger. 2019. Fieldnotes: The makings of anthropology. Cornell University Press.

Sanjek, Roger, and Susan W. Tratner. 2016. eFieldnotes: The makings of Anthropology in the Digital World. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Chiara Pussetti (PhD in Cultural Anthropology, 2003) has lectured at graduate and post-graduate levels in Italy, Portugal, and Brazil. She has researched and published extensively on the subjects of medical anthropology, body and emotions, social inequality, suffering and well-being. Chiara is currently Auxiliar Researcher at the Institute of Social Sciences of the University of Lisbon. Her recent publications include: Remaking the Human: Cosmetic technologies of body repair, reshape and replacement, Oxford, New York: Berghahn Books (2021); Biotecnologias, transformações corporais e subjetivas: saberes, práticas e desigualdades. ABA, UFRGS Edições (2021); Super-humanos. Desafios e limites da intervenção no cérebro. Lisboa Edições Colibrí (2021).

Cite As: Pussetti, Chiara. 2022. “Body on Canvas, Body as Canvas: About Media Mirrors, Plastic Mirages, and Intimate Reflections” In “Taking Note: Complexities and Ambiguities in Writing Ethnographic Fieldnotes,” edited by Magdalena Zegarra Chiappori and Verónica Sousa, American Ethnologist website, 26 August 2022, [https://americanethnologist.org/features/collections/taking-note-complexities-and-ambiguities-in-writing-ethnographic-fieldnotes/body-on-canvas-body-as-canvas-about-media-mirrors-plastic-mirages-and-intimate-reflections]