As an anthropology student in the United States, I have learned that fieldnotes are the bread and butter of ethnographic research. Over the course of my undergraduate, MA, and PhD studies, I have taken a total of 14 courses that introduced me to fieldnotes as “letters from the field,” “a journal,” or “the main data collection strategy for participant observation.” Paradoxically, my training in the ethnographic methods was also marked by a lack of practical engagement with the messiness of the actual process of writing fieldnotes, of the emotional dimension of organizing them, and of the politics of sharing fieldnotes. In this essay, I draw from my experience working with fieldnotes over the course of 24 months while conducting ethnographic research in Lisbon, Portugal to suggest three strategies to start writing, organizing, and sharing fieldnotes. I argue that anthropological training at all levels must include a theoretical and practical engagement with the process of writing and learning from fieldnotes in order to empower anthropologists with the strategies and tools that can make the often messy, emotional, and political dimensions of this process nurturing instead of punitive.

The first time I learned about fieldnotes was in an undergraduate course at the University of Michigan. The class taught us about fieldnotes as a pre-writing process of sorts. We were introduced to our professor’s fieldnotes that he had written in the form of letters from the field. Those letters read beautifully. I remember thinking, “Wow, anthropologists can really capture a whole place with words! I would probably need a camera to be that vivid.” After this introduction, we read several ethnographies and discussed fieldwork as the practice of seeing the world through other people’s eyes. We reflected on John Berger’s Ways of Seeing (2012), which made me think of fieldnotes as a work of art. At the end of the course, we circled back to fieldnotes by writing term papers in the form of letters from the field. I remember feeling embarrassed and lost because all I had seen was those beautifully written letters from my professor, filled with vivid descriptions and insight. In contrast, all I could do was stare at a blank page, petrified by my inability to write something that would prove me worthy of receiving a scholarship to study at that fancy place.

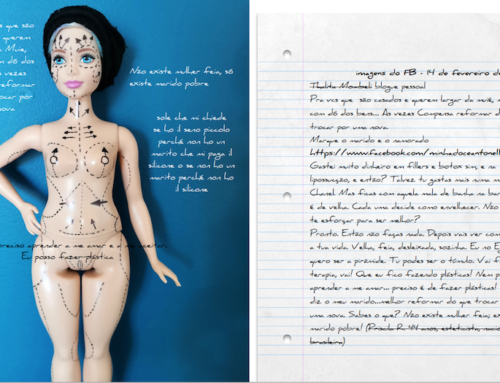

Laís Gomes Duarte. Photo Credit: Laís Gomes Duarte.

A week before the due date, I overcame my shame and shared my struggle with a close friend, Ally, who was an engineering major. I figured that since her expertise must lie in numbers and not in words, her judgment would not be too harsh. To my surprise, my friend had kept a journal her entire life; writing was one of her many talents and passions. Instead of judging me, she kindly offered advice. She was taking an English literature class and showed me what she called “chicken scratches,” the notes with which she had started her term paper. They were messy, grammatically flawed, filled with drawings, and read like a diary. She suggested that I should imagine I’m writing in my diary and fill the blank page with words that expressed everything that scared me about writing, or that I should start by listing everything that I had done during the day. I did not understand her suggestions at first, but over time I was able to take her advice. By writing down what was holding me back, I no longer had a blank page feeding my fears. This advice that Ally gave me is the first strategy I share in this essay.

When you feel paralyzed by the pressure of writing notes, start by writing about what scares you. If that only amplifies your fears instead of making them smaller, then start by listing what you did during the day. Some days your fieldnotes may read like a diary, some days they may read like a to-do list, and some days they may read like beautiful, insightful letters from the field. That’s okay. Anthropologists suggest that fieldnotes often start as “mental notes,” then become “scribbles” that later can be turned into fully developed and detailed descriptions (Emerson et al. 1995, 20). We all need to start from somewhere. Learning how to grow comfortable with the vulnerability of new beginnings is an essential skill for anthropologists. In fact, for the past 24 months, I have taken comfort in recording daily fieldnotes. Some days, I only had enough time to record a voice memo and other days I wrote on my phone while commuting in between field sites. Sometimes I could not leave the house because of COVID-19 lockdown restrictions, so I wrote down a word or a sentence to describe how I felt at that moment. By the time I started writing my dissertation, I had over 600 paragraphs to code and was faced with yet another challenge—the emotional dimension of organizing fieldnotes.

My fear of the blank page was quickly replaced by an avalanche of feelings that emerged as I dove into my fieldnotes, in the hopes of extracting quotes and examples that would help me answer my dissertation’s research questions. At first I froze. Then, I turned to the syllabus from a qualitative research methods class I took as an MA student to look for strategies. I remembered earning that coding fieldnotes could be done in a number of ways, such as “open coding,” “flexible coding,” “selective coding,” and “axial coding” (Strauss and Corbin 2015). While reviewing the literature provided me with strategies to organize and code my fieldnotes, it left me unprepared to constructively engage with the rush of feelings that shaped the process. These feelings ranged from over-excitement, confusion, boredom, and frustration, to inadequacy. I was once again stuck and felt that all the effort I had put into keeping a consistent writing practice wouldn’t help me write my dissertation.

The solution I found was to first digitize all my notes to keep them in one format and in a single place. This helped me to revisit the notes without the pressure of having to extract any useful information from them. I then gave myself a few days to rest and went back to the folder with fresh eyes. I used the search box of each document to look for the key categories that informed my dissertation’s conceptual scheme, copied and pasted quotes from fieldnotes in separate documents, and organized them for each key category. Whenever I felt overwhelmed by the amount of information, I took small breaks and did breathing exercises. This helped me return to my work rejuvenated. The famed Pomodoro Method (Cirillo 2018) proved useful for structuring the time I spent on each step of the coding process. I set small tasks that could be accomplished in blocks of 25 minutes and took 5-minute breaks in-between. At the end of the coding process, I learned to scaffold all parts of fieldnote production and analysis. I realized that being unprepared to organize my fieldnotes early on had caused me to feel overwhelmed and had led me to avoid doing that organizing work from the beginning. In hindsight, I should have included weekly fieldnote organizing sessions into my schedule. Along with the use of the Pomodoro Method, this is the second strategy I suggest for anthropologists who have just started writing fieldnotes or who are learning to organize and code their data.

Another important lesson I learned while writing fieldnotes was that sharing the content of my notes with people I trusted could help me gain clarity related to the politics of accessibility. The first person to read my fieldnotes with me was my 6-year-old godson. I had promised to take a break from coding and take him to read by the lake. When I asked which book I should bring, he pointed to the pink notebook that I had been reading all morning. This unexpected request made me realize that having to explain my fieldnotes to someone with no knowledge of anthropology can be a great exercise in editing. I could only choose examples that would be easily accessible to my godson. As a result of this process, I decided that accessibility should be a criterion in my selection of fieldnotes that would make it into my dissertation. As a student from a historically underrepresented community in the academy and within anthropology, I have experienced the emotional turmoil caused by encountering academic jargon first-hand. I have also decided that my work must be accessible not just to those who share in my privilege of having academic training, but to anyone interested in the topic about which I write. Thus, the third and last strategy I offer here is: share your fieldnotes with a non-academic audience, as it can prepare you to write a dissertation that can engage a wide range of audiences.

Ally’s “chicken scratches” and sound advice helped me face the blank page and inspired me to include my own “chicken scratches” in the writing workshops that I teach today. The Pomodoro Method helped me to negotiate the emotional dimension of organizing fieldnotes. My godson’s reading request made me realize that I should always keep the politics of accessibility in mind. A lack of exposure to the intricacies of writing fieldnotes over the course of my academic training made all parts of writing, organizing, and analyzing more difficult. Anthropology majors should be introduced to all parts of the process of writing fieldnotes, including the steps that precede the beginning of the writing process, the emotional challenges, and the political considerations. More courses that introduce students to the theory and practice of fieldnotes should offer scaffolded assignments informed by strategies that allow students to face the all-too-common fear of the blank page, the frustration and confusion of organizing fieldnotes, and the politics of sharing fieldnotes with multiple audiences. When anthropologists are given the tools that can help them learn from fieldnotes, this data collection process can become nurturing instead of punitive. The discipline, along with the theory it produces, can become all the better for it.

References

Berger, John. 2012. Ways of Seeing: Based on the BBC Television Series with John Berger. London: British Broadcasting Corp.

Cirillo, Francesco. 2018. The Pomodoro Technique: The Acclaimed Time Management System That Has Transformed How We Work. New York: Currency and Penguin Random House LLC.

Corbin, Juliet M. and Anselm L. Strauss. 2015. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publishing.

Emerson, Robert M., Rachel I. Fretz, and Linda L. Shaw. 1995. Writing Ethnographic Fieldnotes. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Laís Gomes Duarte is a PhD candidate at The City University of New York (CUNY), and a proud pet mama who imagines, writes, and fights for a socially equitable, inclusive, loving world.

Cite As: Gomes Duarte, Laís. 2022. “Introduction” In “Messy but Nurturing: Strategies for Engaging Fieldnotes” edited by Magdalena Zegarra Chiappori and Verónica Sousa, American Ethnologist website, 26 August 2022, https://americanethnologist.org/features/collections/taking-note-complexities-and-ambiguities-in-writing-ethnographic-fieldnotes/messy-but-nurturing-strategies-for-engaging-fieldnotes