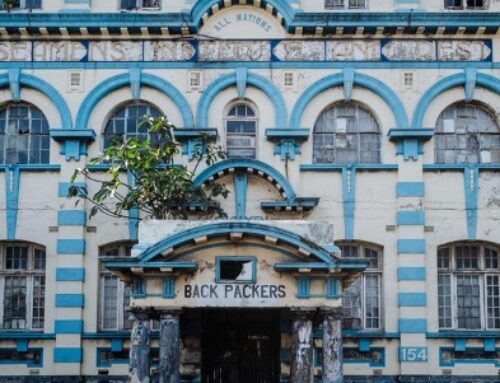

Olosara Beach in coastal Sigatoka, Fiji. The picture shows a “line” of purple, red, and yellow flowers along the beach, with coastal dry forest in the background and various sizes of fossilized coral on the sand. Photo by Ipsita Dey.

I began my late afternoon walk near the Sigatoka River delta, atop a hill that offered me a view of freshwater slowly making its way into the salty Pacific Ocean. I climbed down from my perch, making my way to the beach on the southern edge of the delta. The coral reef, roughly 350 meters ahead, broke the high energy ocean waves so that the water sat almost still within the lagoon and only lapped gently on the beach. I turned to the left and walked along the shore, navigating the perimeter of Muasara lagoon. My destination was Olosara Beach, on the outskirts of Sigatoka, Fiji, a famous picnicking spot about a mile from where I had started.

The ground underneath me was not soft, or white. Sharp objects threatened to puncture the thin soles of my Crocs; they are fossils of an ancient coral reef that now sits on the shore, dull, gray, and dry. I bouldered across this formation for the next few hundred feet. Because I was walking after high tide had passed, water had collected in the crevices of these boulders; the salt water of the ocean burned the cuts at my feet.

I was now closer to Olosara Beach. Thus far on my walk, the ancient reef had hidden the imprints of waves that passed over the sand just a few hours ago. But now, I could see a curved line where the dark brown color of wet sand met the lighter tan color of dry sand. This was as far as the water could reach during the afternoon tide. Along this curved line lay flowers of every brilliant tropical color: orange marigolds, pink hibiscuses, purple morning glories. In a few hours, the sun would set over the horizon; the flowers mimicked the golden hues of twilight sky.

These flowers are offerings from Indo-Fijian Hindu devotees living along the Sigatoka River. During pujas (sacred rituals for birth, death, wedding, and other ceremonies), Hindus offer flowers to deities as representations of their gratitude, devotion, and prayer requests. After the ceremonies are complete, these flowers are placed in the Sigatoka River where they begin their journey towards the ocean (symbolizing God in its expanse and infinity). But the flowers and prayers return to land after high tide. The ocean and lagoon choreograph this final resting place for Indo-Fijian hopes, dreams, and desires. In the midst of long-term ethnonationalist politics that have rewritten Fijian identity in the exclusivist terms of indigeneity, Indo-Fijians (or descendants of 19th and 20th century Indian indentured plantation laborers) must find ways of belonging to land outside of categories of political representation, land ownership, and autochthony. The flowers’ return to the shore indexes the forms of metaphysical belonging Indo-Fijians claim to the mythologies, cosmologies, and more-than-human deities of the landscape.

For roughly 60,000 Indian indentured laborers brought to Fiji in bonded labor, known colloquially in Hindi as “girmit,” worlds ended in the journey across the kala pani (black waters) and in harsh and exploitative conditions on sugarcane plantations. But still, the severing of ties with the “homeland” (without promise of return) and the exhaustive labor practices and dehumanizing humiliation endured under vicious plantation overseers produced a new identity of jahaji bhai (ship brotherhood). After months of dwelling in dark, crowded slave barracks (previously used to transport African slaves in the Middle Passage), Indian indentured laborers waded through waist-deep waters, dragging lifebuoys behind them until they reached the Fijian shore. “[Indentured] people…refer to [this] as the moment of origin or genesis in the new land” (Mishra 1996), often metaphorizing the ship as traumatic womb and the short, wet trip from ship to land as the process of birth, of arrival into a new landscape. Here, Mishra borrows heavily from Gilroy’s theorization of the slave ship as a chronotope (Gilroy 1993), where “time stops and restarts…and linear history is broken” (Clifford 1994). Oceanic epistemological frameworks imagine the body as of place, “meaning the land, food, and families that nourish the body from birth constitute that body as fundamentally located within ancestral relations” (Hardin 2021). Contextualizing Indo-Fijian embodied knowledges within this framework brings sugarcane plantation histories to the forefront of discussions about the “constant movement and exchange of bodies, knowledge, and materials” (Teaiwa 2007) across Pacific worlds. Worlds were simultaneously ending and beginning on island coasts, where Indian indentured laborers met their new futures on Fijian landscapes, and indigenous Fijians (iTaukeis) found plantations at the carefully policed borders of their villages. Framing Fiji as an always changing landscape disturbs the colonial and ethnonationalist imagination of a “pristine,” “untouched,” pre-climate-change vision of natural beauty in the Pacific.

At the time of my walk, I took this photo because of the composition of vibrant colors: the flowers juxtaposed with the green jungle, blue sky, and beige sand produced a seemingly over-saturated image of tropical abundance. But after reflecting on the long-standing tensions over land tenure and political belonging between indigenous and Indo-Fijian communities, returning to this photo made me realize: the Fijian shoreline is always shifting. It extends further into the ocean in deep time, signaled by the fossilized coral that sits on contemporary beaches as remainders of an ancient coastline. It changes in quick time as the ocean creeps onto land at hightide, flowers from upstream Hindu pujas outlining the imprints of waves; tomorrow, the waves and flowers together will etch different lines onto the sand. Shifting landscapes point to shifting identities, and destabilizes the static imagination of land and place that fuels indigenous ethnonationalist rhetoric. It is this indeterminacy of place that the flowers on the beach invite us to ponder – the blurred distinctions between sky and Earth, ocean and land, past and future – that can allow a reimagining of Fijian belonging beyond racial binaries, imposing settler-colonial logics of property-defined personhood, and persistent plantation logics that define land through labor, commodities, and boundaries.

References

Clifford, James. “Diasporas.” Cultural Anthropology 9, no. 3 (1994): 302–38. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1525/can.1994.9.3.02a00040.

Gilroy, Paul. The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1993.

Hardin, Jessica. “Moving Materialities: Oceanic Epistemologies and Embodied Knowledge Production in Pentecostal Women’s Health Mentorship in Samoa.” American Anthropologist 125, no. 2 (2023): 239–51. https://doi.org/10.1111/aman.13837.

Mishra, Vijay. “The Diasporic Imaginary: Theorizing the Indian Diaspora∗.” Textual Practice 10, no. 3 (1996): 421–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502369608582254.

Teaiwa, Katerina Martina. “South Asia Down Under: Popular Kinship in Oceania.” Cultural Dynamics 19, no. 2–3 (July 1, 2007): 193–232. https://doi.org/10.1177/0921374007080291.

Ipsita Dey recently graduated from Princeton University with a PhD in Anthropology and a Graduate Certificate in Environmental Studies. In Fall 2024, she will begin as an Assistant Professor in the Comparative History of Ideas Department at the University of Washington, Seattle. Her research focuses on indigenous politics, indentured labor diasporas, and plantation afterlives in Fiji.

Cite as: Dey, Ipsita. 2024. “Shifting Landscapes, Shifting Identities: Oceanic World-Making in Fiji”. In “Photographic Returns,” edited by Christina Kefala and Ipsita Day, American Ethnologist website, 23 June. [https://americanethnologist.org/online-content/collections/photographic-returns/shifting-landscapes-shifting-identities-oceanic-world-making-in-fiji-by-ipsita-dey/]

This piece was edited by American Ethnological Society Digital Content Editor Katie Kilroy-Marac (katie.kilroy.marac@utoronto.ca).