So many thoughts lined up in my head as I looked for the vaccination room. I was sweating. The metallic chairs in the hospital’s hallways reflected a cold light that clashed with the hot and sticky air of midday in Cali, Colombia. It occurred to me, though, that maybe what was making me sweat was the sticky fear of missing out (FOMO) that kept me from going home after 5 hours of interviews. I noticed I could no longer stay focused. The voice in my head urged me to keep going, telling me that this next interview could be the missing piece of my puzzle. As I made my way to the waiting room, the voices of a woman and child disrupted my thoughts. The child was building a trembling castle made from their shoes. They might have just been vaccinated, I realized. “Maybe I can ask her a few questions about her experience,” I thought to myself. “Then, even if I can’t find the nurse I am looking for, I will have gathered more data.” I hesitated—approaching somebody who had just received a shot of the COVID-19 vaccine didn’t sound ethical. Still, I felt tempted. Having more data before wrapping up this second period of fieldwork would make me feel better. “Yes, exactly—me not them,” I realized. “Are these necessary data or am I just trying to appease my ‘carnivorous anxieties[1]?’ They will end up eating me if I don’t ‘sacrifice’ somebody else.” Right then, the woman turned and caught my eye: I realized I might have whispered those words out loud.

So many thoughts lined up in my head as I looked for the vaccination room. I was sweating. The metallic chairs in the hospital’s hallways reflected a cold light that clashed with the hot and sticky air of midday in Cali, Colombia. It occurred to me, though, that maybe what was making me sweat was the sticky fear of missing out (FOMO) that kept me from going home after 5 hours of interviews. I noticed I could no longer stay focused. The voice in my head urged me to keep going, telling me that this next interview could be the missing piece of my puzzle. As I made my way to the waiting room, the voices of a woman and child disrupted my thoughts. The child was building a trembling castle made from their shoes. They might have just been vaccinated, I realized. “Maybe I can ask her a few questions about her experience,” I thought to myself. “Then, even if I can’t find the nurse I am looking for, I will have gathered more data.” I hesitated—approaching somebody who had just received a shot of the COVID-19 vaccine didn’t sound ethical. Still, I felt tempted. Having more data before wrapping up this second period of fieldwork would make me feel better. “Yes, exactly—me not them,” I realized. “Are these necessary data or am I just trying to appease my ‘carnivorous anxieties[1]?’ They will end up eating me if I don’t ‘sacrifice’ somebody else.” Right then, the woman turned and caught my eye: I realized I might have whispered those words out loud.

The relationship between anthropology and photography is as old as the discipline of anthropology itself, and as old as the relationship between anthropology and anxiety (Edwards 1992; Rabinow 2007). Photography is an important tool for ethnographic research because pictures can contain and evoke the past. This skill is gold for an ethnographer, but even more for a researcher engaging with “patchwork ethnography” (Günel et al. 2020). Because of a combination of global and personal circumstances, namely a pandemic during my first year of PhD program combined with a lack of funding, I had to abandon the plan of doing a full-time PhD with a long-term fieldwork, as in the “best” anthropological tradition. Instead, I captured patches of narratives and practices of pharmacovigilance through short-term field visits over a period of three years. Using “patchwork ethnography” as a methodological compass, I tried to think “with, rather than against” (5) the external constraints and personal circumstances that shaped knowledge production and the knowledge produced during my field visits. It sounded like a bright plan when I read it, but I found myself groping in the dark, stressed out, and full of insecurities when navigating the field.

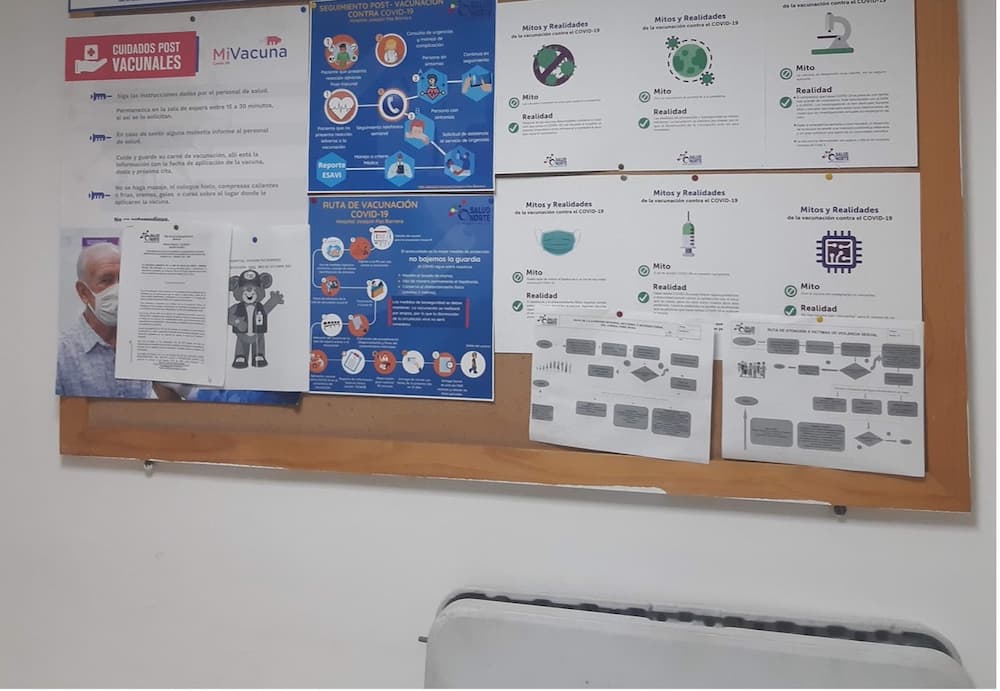

While I nodded my head as a greeting to the woman, I found myself wondering how I had slipped into this way of thinking that bordered on an extractivist approach to data collection. The thought horrified me so that I opted to spare the woman my questions and instead kept looking for the nurse, as my previous interviewee suggested I should, and as my FOMO obliged me to do. But something else caught my attention. Next to the door was a board covered with posters about the COVID-19 vaccination. I stared at it, but I was so tired that I could not actually process what I was seeing. “Humm it could be interesting. I will look at it later, with a fresh mind.” I pulled out my phone and took a picture of the board, feeling relieved that I could capture all of this information and make sense of it later.

The photo I chose for this essay is flat and a bit out of focus, but the objects in the frame are valuable for exploring the narratives and practices of public health. I notice now the careless way in which the notes were layered, one on top of each other, as if to say, “we need to put this out there, but it doesn’t really matter if anyone can actually read it.” I chose this photo for what it did and what it still does, beyond its original purpose. In the moment I pressed the button to take the picture, it gifted me with extra time and space. It calmed down my “carnivorous anxieties”. The fear of not being able to collect enough data is common amongst anthropologists. Looking at this picture now, I realize that my ethnographic research was marked by a distinct attempt to bend time, in a breathless run of turning three months of fieldwork into six. “To what effect?” I wonder now. Fatigue, anxiety, and a feeling of always being rushed overwhelmed me while collecting these patches. Confusing quantity and quality became easier than I thought.

Today, this picture gifts me with something else a “space of connection.” This picture did not only crystallize the objects in the frame, but also what was happening outside those borders. By reactivating the affective and ethical entanglements of my fieldwork, this photo allows me to reach a deeper level of reflexivity about knowledge production. Going back to my fieldwork diary, I find traces of my concerns about the time constraints of my research. On multiple occasions, I doubted whether I could even call this a “real ethnography.” I only breath a sign of relief recognizing these thoughts in the experience of Fratini, who describing her experience with patchwork ethnography discloses similar concerns (Fratini et al. 2022, 7), as well as the words of Jackson (2010), who feared that he had not collected enough data for his PhD dissertation after a full year of fieldwork. Reflecting on these texts prompted me to turn my attention from the effect of time constraints to the affects of time constraints. Time, rush, anxiety, and FOMO are the very threads that weave my ethnography together. How do they shape the process of knowledge production, the knowledge produced, and the ethical insights offered along the way? How do they mediate the relationship between an ethnographer, their interlocutors, and the field? As I think through these questions, I find resonance in Edwards’ reflection that “photographs and responses to them are woven into the very fabric of contemporary experience and the negotiated relations between past, present and future, and living and dead, spirits and ancestors, and places and spaces of connection” (2015, 248).

Notes

[1] This expression, used also in my title, is inspired by the title of the book Las Ansias Carnivoras de la Nada (The Carnivorous Anxieties of Nothing), written by Alejandro Jodorowsky (2007).

References

Edwards, Elizabeth. 2015. “Anthropology and photography: A long history of knowledge and affect.” Photographies 8 (3), 235-252

Edwards, Elizabeth. 1992. Anthropology and Photography, 1860–1920. New Haven, CT, and London: Yale University Press in association with the Royal Anthropological Institute

Günel, Gökçe, Saiba Varma, and Chika Watanabe. 2020. A manifesto for patchwork ethnography. Member Voices, Fieldsights, 9

Jackson, Michael. 2010. From anxiety to method in anthropological fieldwork. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Jodorowsky, Alejandro. 2007. Las ansias carnívoras de la nada. Siruela: Debolsillo.

Fratini, Annamaria, Susan R. Hemer, and Anna Chur-Hansen. 2022. “Peeking Behind the Curtains: Exploring Death and the Body through Patchwork Ethnography.” Anthropology in Action 29(3): 1-13

Rabinow, Paul. 2007. Reflections on Fieldwork in Morocco: with a New Preface by the Author. University of California Press

Maurizia Mezza is a PhD candidate in medical anthropology at the University of Amsterdam. Her research focuses on epidemiology, vaccination, and pharmacovigilance in relation to HPV and Covid-19 vaccination.