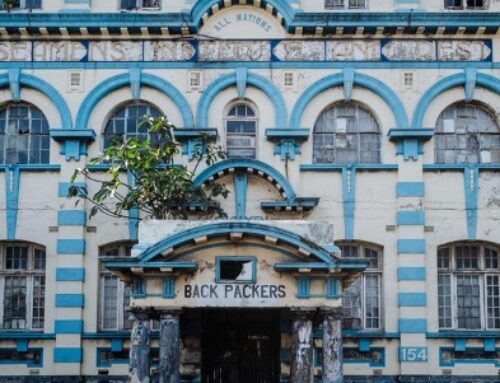

Palihan (2020) is a mixed-media statue artwork by local artists Duvrart Angelo and Lulus Setyo Wantono. Photo by the author, June 2023.

A Statue at YIA

Entering the Yogyakarta International Airport (YIA) arrival hall, I stopped in my tracks to stare at a stunning piece of artwork. Others were similarly struck by the sight. I noticed passengers who had just stepped off a plane taking photos in front of the statue while making their way through the arrival hall. The art piece is titled Palihan.

Palihan is one of many contemporary artworks installed in along the walls and in the halls of the airport. The statue bears a written caption that tells the story of Prince Dipanegara, a national hero, Javanese mystic, and leader of the “holy war”—known as the Java War—against the Dutch between 1825 and 1830 (Carey 2015). Dipanegara was chosen by two local artists, Duvrart Angelo and Lulus Setio Wantono, to recall the local history of Palihan village, which was closely related to the prince.

When I later interviewed the curator for YIA’s art programs, Bambang “Toko” Witjaksono, he admitted that there were still doubts about whether the story of Prince Dipanegara in Palihan was true. Some thought it was little more than a myth. But many people believed, and the airport authority never tired of asserting that Palihan was where Prince Dipanegara and his army devised strategies to fight back against the Dutch during the Java War. The Palihan artwork was made to symbolize the prince’s struggle.

However, Palihan was but one of five villages in Kulon Progo Regency, Yogyakarta, that had to be relocated for the new airport in the early 2010s, and again later for a 600-hectare aerotropolis development zone. Almost 10,000 people from these villages (39% of the total population) were forced to move between 2016 and 2019 for the sake of the new airport.

In contrast to other villages, Palihan is the only village that did not move all of the residents in the area. “Only” about 1327 people from Palihan (approximately 57% of its residents were relocated (Dewi and Salim 2020).

Searching for the Meaning of Palihan

I was intrigued by the etymology of the Javanese term palihan: what does it mean? The official website of the art consulting firm for YIA noted that palihan was believed to have originated from the Sanskrit term pali or pepali, meaning message or advice.

Palihan is also interpreted as peralihan. In English, this means a “shift,” denoting an event that changes the place, position, form, or direction of something and is replaced by another.[i] If so, palihan can also represent malih or “to transform immediately.” The latter definition is more logical and closer to the heroic story behind the Palihan artwork.

I asked Yosephin Rahayu, a Sanskrit and Javanese language expert from the Universitas Gadjah Mada what she thought. It is questionable, she explained, that pali or pepali means advice or message, as pali is not even known in Sanskrit.

If pali refers to pāli, it would have meant a protector or a ruler, which is usually a compound word, an affix must be attached to the word—either in front or behind it. If it refers to pālī, it means a long pond that functions as a water receptacle. Pepali is also impossible since Sanskrit does not recognize the vowel ê (like the e sound on merge /mɜːrdʒ/).

Meet Dalijo, a Palihan Resident

I landed on a Saturday evening at YIA; my flight from Jakarta had been delayed for four hours. I was frustrated and exhausted, all the more so because I had missed the airport train I had booked that evening. The only airport train still running could take me as far as the city center, but for this train I was facing a 1.5 hour wait. My final destination was in the northern area of Yogyakarta, near the foothills of the volcanic Merapi mountain some 70 kilometers away, or a two-hour drive from the airport. Quite far.

I didn’t have many options after I missed the train because public transportation was limited, especially during the evening. This is a common problem in many cities in Indonesia, with the exception of Jakarta. The easiest way to travel is to take one of the online taxis provided by the airport transportation service, but it is quite expensive compared to the train fare which is only about 40,000 IDR ($2.5 USD); it looked like I would have to spend nearly 400,000 IDR ($27 USD) for one trip.

Resigned to find an online taxi, I went to the arrival hall, where transportation and accommodation services are actively offered to arriving passengers. A man, an online taxi worker, accompanied me to the taxis in the parked queue. Another lean-faced man with dark brown skin wearing a GoJek taxi uniform stepped towards me. He asked for my taxi queue number. After checking it on his smartphone, he stowed my luggage in his car.

Dalijo,[ii] a 38-year-old father of a newborn son, was one of the Palihan inhabitants who did not relocate to the new village back in 2017-2018. As he recalled, during the land acquisition by the airport authority, almost half of Palihan territories were not used for airport construction. He and his family, then, remain in their “half village,” where he lives in an old small house with his parents. Like many other Javanese villagers, Dalijo’s parents do odd jobs or peasant labor for their livelihood. The eldest of his two brothers works as a laborer on a chicken egg farm in Brosot, 25 km away from their village.

“From smallholder labor to online taxi driver labor,” Dalijo said to me in Javanese as he described his work before becoming a GoJek taxi driver at the airport. He used to be a day laborer on a watermelon and chili farm on the coast of Glagah, where the YIA aircraft runway is located today.

In order to work as a taxi driver, he has to rent a car from his uncle, who is wealthier than his nuclear family. His uncle bought a new car with the compensation money he received from Angkasa Pura I, the airport authority, for his chicken farmland.

Comparing his life before and after the YIA, Dalijo admitted being grateful now that he can regularly earn money—he makes between two and three million rupiahs (approx. $190 USD) every month. He knows that his life is still precarious because he shares 40% of the profits with his uncle, the car owner. He also must pay around 1,000,000 IDR ($65 USD) every month to the Putra Palih cooperative, a former farmers’ cooperative that now acts as the GoJek taxi driver agent for the Palihan people.

Like Dalijo, 40 other taxi drivers in green uniforms in a long queue of cars wait for passengers at the airport each day. The more time they spend working, the more money they can earn. But, in my view, this international airport-aerotropolis-era condition is not necessarily better than before when they were peasant laborers.

A place and a position

Palihan presents a paradoxical story between the heroic imaginating of a lost past, on the one hand, and ordinary people’s experience in real life, on the other.

When I got home, I delved into those stories once again and started thinking about Palihan as both a place and a position (Bhimull 2017). As a place, Palihan is part of a new aerotropolis zone that somehow recalls memories and histories of how people were displaced, stayed, and struggled; how state promises of the “future city” are being carried out; how the rural landscape has transformed; and how people are stuck with their precarity. It also shows how local artists are engaging with the airport authority to make the airport more attractive.

Palihan, as a position, is a strategic orientation (Bhimull 2017). This orientation points towards the vast rural-urban transformation of its space, place, and people in Kulon Progo. As it grows even more globally connected, the airport and aerotropolis evoke hope for gradual economic growth.

The reason I begin this article with the artwork is that it makes me think about my research direction and plan. Before seeing the artwork, I primarily wanted to know how airport planners work to transform airports and surrounding areas.

The artwork is not just an accessory or attribute intended to make the airport more beautiful. Considering Erik Harms’ (2012) conception of “beauty as control” has inspired me to think more about the aesthetic dimensions of airport development and to explore new ways of apprehending urban infrastructural development.

Notes

[i] Palihan, https://www.artcab.id/portfolio/palihan/.

[ii] Dalijo is pseudonym.

Acknowledgments

I would thank to Christina Kefala (University of Amsterdam) and Ipsita Dey (Princeton Univerity), editors of this AES Collection. I am also grateful to Yosephin “Simbok” Apriastuti Rahayu (Leiden University and Universitas Gadjah Mada), Dr. Tina Harris and Dr. Luisa Steur (University of Amsterdam), and Meivy A. Larasati (Bakudapan Food Study Group) for their feedback and support.

References

Bhimull, Chandra D. 2017. Empire in the Air: Airline Travel and the African Diaspora. New York: NYU Press.

Carey, Peter. 2015. The power of prophecy: Prince Dipanagara and the end of an old order in Java, 1785-1855. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill.

Dewi, Ni Luh Gede Maytha Puspa & Salim, M. Nazir. 2020. Berakhir di Temon: Perdebatan Panjang Pengadaan Tanah untuk [New] Yogyakarta International Airport (YIA) (Ended up in Temon: a long struggle of land provision for the new Yogyakarta International Airport). Yogyakarta, Indonesia: STPN Press.

Harms, Erik. 2012. “Beauty as Control in the New Saigon: Eviction, new urban zones, and atomized dissent in a Southeast Asian city.” American Ethnologist 39(4):735-750.

Khidir M. Prawirosusanto is a PhD candidate in anthropology at the University of Amsterdam and a junior lecturer at the Department of Anthropology, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Indonesia.

Cite as: Prawirosusanto, Khidir M. 2024. “Palihan: Airport Artwork, Place, and Position”. In “Photographic Returns,” edited by Christina Kefala and Ipsita Day, American Ethnologist website, 23 June. [https://americanethnologist.org/online-content/collections/photographic-returns/palihan-airport-artwork-place-and-position-by-khidir-m-prawirosusanto/]

This piece was edited by American Ethnological Society Digital Content Editor Katie Kilroy-Marac (katie.kilroy.marac@utoronto.ca).