The categories of perception that agents apply to the social world are the product of a prior state of the world. When structures are modified, even slightly, the structural hysteresis of the categories of perception and appreciation gives rise to diverse forms of allodoxia

(Bourdieu 1996, 219)

On March 13th, my phone pinged with a text message from a college friend:

“How’s it going? Enjoying the apocalypse so far?”

“I mean, I’ve been voluntarily quarantined in my apartment writing my dissertation since January so it’s basically business as usual for me. U?”

It was a joke that I would make repeatedly over the subsequent weeks, as friends with whom I hadn’t spoken in months or years emerged from the ether, in shock from abrupt changes to their work and routines, lonely and bored, looking to hear a voice that wasn’t their own (or their partner’s/children’s).

I had been writing my dissertation full-time since January. I applied for dozens of academic positions and post-docs in the fall, and, in order to finish my dissertation in time to begin one of these possible positions, activated a registration status with my university’s bureaucracy that allowed me to write full-time during the spring semester. At the time, this seemed like the practical thing to do. The fine-tuned intellectual work of finishing a substantial piece of academic writing is virtually impossible when one’s energies are devoted, for example, to teaching. The downside was that this full time write-up status did not qualify as formal enrollment.

In January and February I gradually saw my ties to the university that had granted me identity and structured my life over the previous seven years disappear, one-by-one. First, my health insurance lapsed. Then, my library privileges were revoked. Then, I started getting notices from my student loan servicer that I had entered “grace period.”

Then, sometime in mid-February, my university gym membership lapsed. My only day-to-day structure since a teaching appointment for the fall semester ended were my Monday-Wednesday-Friday spin classes, a ritual around which I had managed to suture some sense of dignity and self in the context of a rolling series of rejections, a year of personal tragedies and family upheavals, and a growing sense that I had become a burden on my department and advisors.

Throughout this time, I continued to write in isolation. I had no choice. My registration status required that I file by the end of spring semester. The deadline was nearing, the department was ignoring my questions about what options were available if no academic appointments came through, and I knew the world kept turning no matter how upended I was feeling. I would awaken with anxiety sweats at 3am, have periodic crises of confidence about who I am, and, attempting to sift through the noise for usable ideas, sit staring at my computer for hours. What was the point, if there was nothing on the other end?

In his well-known theory of habitus, Bourdieu describes the “hysteresis effect,” which occurs when extant social conditions and change outpace the ways that we, as individuals, are socialized or trained to accommodate and to expect (Bourdieu 1977, 78). This effect is rendered most vividly in The State Nobility (1996), which describes “victims of hysteresis” (1996, 212) as experiencing “disorientation” and “indifference,” “in a bewildering universe where nothing is clear, nothing is certain” and falling into “strategies of despair” such as “submit[ting] to the advice of professional or volunteer guidance counselors who for the most part only reinforce their (socially constituted) inclination to choose the paths they see as the safest” (1996, 219-220).

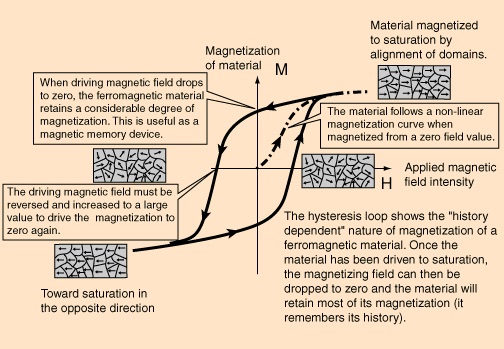

Hysteresis (Young in Hu 2016, 18)

Bourdieu captures here a part of my own experience over the period between January and March, before the pandemic struck the United States, that has been extremely difficult to negotiate, articulate, and understand—much less muster the courage to share. And yet, despite a norm of institutional silence—one is expected to convey self-assurance, even mastery—I know that my experience is common. Among my colleague-friends at the same stage cross-disciplinarily, kvetching-sessions reveal remarkably similar patterns—what amounts to a structurally produced cynicism. Having been conditioned to believe that hard work and pragmatic action will lead to a desired (indeed, the only desirable) end—i.e., an academic job—the contrast between, on the one hand, our habitus engendered by years of training and reinforcement by mentors who matured in a very different environment, and, on the other hand, the reality of the academic job market in the present, is profound. This cognitive dissonance manifests in feelings of disillusionment, abandonment, and bitterness. We resist sharing these feelings, because in academia there is no virtue in failing, despite an objective environment in which most fail. The moments when we feel safe enough to share, we experience euphoric connection—we are seen. And yet, these positive feelings are short-lived, as the recognition of structural disadvantage does little to alleviate the ongoing suffering that inevitably accompanies toiling away for an increasingly elusive end.

In spite of this disillusionment, eventually, and miraculously more or less on schedule, I merged my chapters and granted myself the privilege of telling people I had a “full draft” that I sent to my advisor. And then, huzzah! A Zoom interview for a job!

That was on March 13th.

On March 16th, Alameda County (home of UC Berkeley) was among the first jurisdictions in the United States to issue a “shelter in place” order restricting movement for anything other than to meet “essential needs” (Arango et al. 2020). Over the following days and weeks, similar orders were issued around the country. The nation roiled—seemingly overnight, livelihoods were snatched away, futures were obliterated, and worlds shrunk to the size of one-bedroom apartments. The prospect of planning for a week into the future was laughable, much less one month, six months, a year. Restaurants shuttered. Gyms went under. Big-name retailers filed for bankruptcy en-masse. Pending postdoc and job lines were pulled, and whatever academic job market may otherwise have manifested in the fall was quickly squashed.

And there I sat, behind the desk in my living room where I had been dissertating since January, with the same sense of isolation and upendedness, suppressing the same sense of dread and uncertainty about the future that had plagued me for months already.

Oddly, in spite of this bleak scenario, the period since March 13 has perhaps been the most productive of my graduate-school career. I feel freed from the tyranny of expectation that something predictable lies on the other end of this eight-year doctoral endeavor. Indeed, there is something liberating about being part of a crowd—uncertainty in isolation breeds a narrative of individual deficiency, but I am now in the company of tens of thousands facing an uncertain near-future. We have all been made aware that we are victims of hysteresis. While the dissertation-writing phase of this degree has been defined by isolation, I now find myself connecting with other humans—friends, colleagues, scholars—with greater frequency and quality than I have in quite some time.

With nothing left to lose, I throw myself into my work, not out of obligation, but out of a sheer sense of “What else would I be doing right now? Who am I so fearful about impressing?” I worry less about putting myself out there, because who knows where I’ll be come next year? I submit an article, I begin another, I co-organize a panel for the annual meetings, I plant the seeds for a collaborative project, I reach out to scholars whose work I admire. I volunteer to submit an entry to American Ethnologist’s “Pandemic Diaries” series.

I do not know if I will find a place in academic anthropology. But then again, nobody at this stage of the doctorate ever does. Covid-19 has catalyzed the revealing of structures of arbitrary inequity undergirding even the most loudly virtuous ventures. But these structures were always there—one hundred years ago, Max Weber observed:

Whether a lecturer ever attains the position of a full professor…is simply a matter of chance. True, luck is not the only factor, but it plays an unusually predominant role—I can hardly think of another career in the world where chance plays such an outsize part (Weber 2020, 7).

In the context of this long-standing but little-acknowledged reality, Covid-19 has given me a paradoxical sense of community in isolation and uncertainty. It has validated, at a collective level, the truth that nothing has ever been certain. This new transparency has, for me, engendered energy, previously sapped by the disillusionment produced of hysteresis, to strive for “inspiration” (Weber 2020, 12). It has opened up a path for me to let go of expectations, from others but mostly from myself. It has enabled me to focus on the now, to reveal with greater clarity the aspects of the work that bring me pleasure, and to let go of the neurotics of success. I do not know if this circumstance will sustain, and at some point I will be forced to re-confront the practical and worldly (everyone needs health insurance, after all). But for now, being kind to myself involves allowing myself to be energized by this collective uncertainty; to express empathy for others who struggle, as I do, with disruption and ambiguity; and to embrace work and writing without expectation.

The author’s cat, vying for a co-authorship credit

For many (perhaps most) others, this collective uncertainty is far from liberatory. I occupy a position both of relative disadvantage, but also of relative privilege in confronting Covid-19. Student status insulates me from capitalist demands that I expose myself to infection or else lose my livelihood. Affiliation with the university grants me access to low-cost healthcare at least for a few more months. My only dependent is a small cat with seasonal asthma. I hear the stories that my partner, a mental-health provider working on the front lines with San Francisco’s un-housed population, shares about his work, and I feel fierce compassion and deep guilt. Who am I to complain about uncertainty, when thousands in my city don’t have access even to the illusory attachments of “cruel optimism” (Berlant 2011) as a permanent condition of existence? I also hurt for my colleagues who are overwhelmed with caregiving obligations, or who are paralyzed by the existential weight of a world collapsing. My account is meant only as a personal reflection, in the spirit of a diary, on my experience of the last six months. In many ways this account is particular, but in some ways I suspect that it speaks, at least in part, to a set of shared experiences not often voiced in the professionalized habitus of the academy.

References:

Arango, Tim, Thomas Fuller, John Eligon, and Conor Dougherty. 2020. “To Battle Virus, 7 California Counties Order Everyone to Stay Home.” The New York Times, March 16, 2020, sec. U.S. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/16/us/california-covid-19.html. Accessed June 7, 2020.

Berlant, Lauren. 2011. Cruel Optimism. Durham: Duke University Press.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1977. Outline of a Theory of Practice. Translated by Richard Nice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

———. 1996. The State Nobility. Translated by Lauretta C. Clough. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Weber, Max. 2020. Charisma and Disenchantment: The Vocation Lectures. Edited by Paul Reitter and Chad Wellmon. Translated by Damion Searls. New York: New York Review Books.

Xiaocao, Hu. 2016. Synthesis and Characterization of Magnetically Hard Fe-Pt Alloy

Nanoparticals and Nano-Islands (Doctoral Dissertation, University of Delaware).

Retrieved from: http://udspace.udel.edu/bitstream/handle/19716/17738/2016_HuXiaocao_PhD.pdf?isAllowed=y&sequence=1. Accessed June 7, 2020.

Cite As: Sangren, Kristin, M. 2020. “Community in Isolation, Inspiration from Uncertainty”

In “Pandemic Diaries,” Gabriela Manley, Bryan M. Dougan, and Carole McGranahan, eds., American Ethnologist website, 15 June 2020, [https://americanethnologist.org/features/pandemic-diaries/making-sense-of-things/community-in-isolation-inspiration-from-uncertainty]

Kristin M. Sangren is a PhD candidate in sociocultural anthropology at the University of California, Berkeley. Her research focuses on law, subjectivity, and social morality in China.