Right before I left for vacation, I went to a meeting about zonas rezagadas (a program for areas within Chile that are “lagging behind”). One of the main goals of this program is to improve connectivity in the Aysén Region of Chilean Patagonia. I live in a small town at the end of the highway at the southernmost point of the region. The nearest settled area is over three hours away on an unpaved road interrupted by an hourlong ferry ride across a fjord. My town is classified by the government as an “extreme zone” in an “isolated region” in a province that is now “lagging behind.” Connectivity is the proposed solution to the “problem” of isolation. Building roads and improving transportation infrastructure is supposed to bring places like my town “up to speed” with the rest of the country. The presenter explained that these connective investments were not only supposed to help local people living in “isolation,” but that they are necessary for a region transitioning from ranching to the 21st century tourist economy. After the presentation, most people signed a document stating their approval of the projected budget.

The night before I left town, a friend texted me, “Don’t bring Coronavirus back here. Hahahaha.” In a small town such as ours, several people had told me that the virus would never cross the fjord. It was too cold here in the “Capital of the Patagonian Glaciers” to survive. Like most things in the news, many believed that our town was immune to what was happening in Chile and the world. Coronavirus was something we joked about as we sneezed or tossed back the eponymous Mexican beer. That was the beauty of living in isolation.

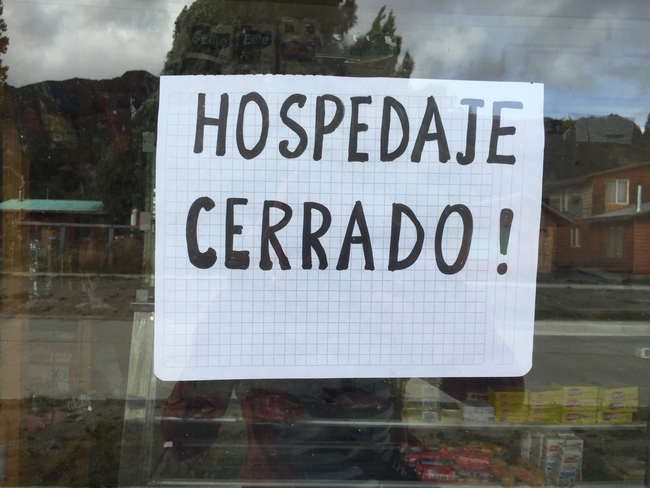

The ferry waiting area on the other side of the fjord is covered in stickers from around the world. Due to lodging and restaurants being closed, the sign recommends that visitors not continue their journey

I arrived in the regional capital two days later and it was no laughing matter. Suddenly people in the hostel were talking to me in English about their escape plans. The next day, on a bus still farther north, the news arrived that the first case had been discovered in the Aysén Region. It was our neighboring town, only five hours away. A British tourist had disembarked from a cruise ship, interacted with locals, and was airlifted to the regional capital. Suddenly, something that seemed very far away was strikingly close. The day the news arrived, a local bus was on its way home from the infected village. People started to worry about this bus bringing Coronavirus to town. The bus operators assured everyone that the passengers would have to register with the police and the bus service would be suspended for twenty days.

When I finally reached my friend’s house in the next region north, the conversation was about staying or leaving. Chile made moves to control the spread of Coronavirus at the national level. Each day there was a new development. Argentina was going to close its borders. Chile would no longer allow anyone but Chileans and foreign permanent residents into the country. My friend in Santiago told me her brother-in-law had just come home from New York with Coronavirus. I cancelled the rest of my trip and tried to get back to my fieldsite as soon as possible. We had heard rumors of domestic travel restrictions as well. The president had declared a “State of Catastrophe” for ninety days, giving the military the power to enforce order if needed. As I took the first bus back home, I sighed with relief when I crossed back into my region. I texted my friends in the regional capital to make sure they could still host me at their hostel, and they said they were only accepting pre-existing reservations and gente conocida (people we know) like me. They were helping people rebook their cancelled flights in order to empty the hostel within three days. They said, “It’s a great business we have here, but we have to be responsible and take care of our families.”

Sign reads: Lodging closed

As I rode home, I closely followed the discourse on the two town WhatsApp chats I am a part of. Amidst all the practical matters of increasing restrictions, a new xenophobia was growing in town. One of the bus drivers took a photograph of several foreign cyclists and asked why tourists were still coming to town. Another responded, “Let’s put up a barricade at the cattle guard and not let them in!” A different voice tempered the conversation by saying that it was shameful to blame tourists when it was a worldwide epidemic. One woman, defending her xenophobia, said she was “just trying to protect her own.” She said if “they” keep coming, maybe they should shut down the road except to cargo. There is now a sign on the other side of the fjord explaining that all of the lodging and restaurant options in town are closed, so tourists are “not recommended” to visit. Most recently, the mayor assured the town that he had spoken with the ferry captain and no foreign tourist would cross the fjord.

With this new xenophobic rhetoric (no one was talking about Chilean tourists, after all), I felt incredibly lucky to have my temporary resident visa. Every time the buses asked me for my passport, I gave them my Chilean identity card instead. “Oh, you have a cédula.” The paranoia that townsfolk started feeling towards foreigners translated into my own paranoia about how I would be treated upon my return. Many people know me, or at least recognize me in town. During the tourist season, however, with so many gringos walking around in hiking boots and Gore-Tex, some thought I was just another foreign tourist. I have been trying hard to be recognized as a something other than that. With over six months in town, I am now an official resident and qualify for local benefits. But I will always have my gringa face. Even those who know me well often say, “You’re going to leave and never come back.” They mark me as a temporary, not a permanent resident.

When the road reached our town twenty years ago, the mayor had declared that everyone would want to come here. The end of the road would be a great tourist destination. And it is—for a certain type of tourist. It’s one of the most beautiful road trips imaginable. People travel by bike, car, or even bus for the journey, and reach our town at the end of it. The mayor and entrepreneurial residents have been counting on tourism, investing in infrastructure, and taking out loans to build summer cabins. Now with the tourist season cut short, many people are wondering if it was right to place their faith in it. In less than a week, our town went from yearning to be a top tourist destination to revaluing its isolation. Yesterday, on the group WhatsApp someone posted a photograph from another town (that, oddly enough, was going to be my second fieldsite). It is the most popular tourist destination in the whole region, a place some refer to as a “sacrifice zone” to index the intense effects of tourism. Locals had taken matters into their own hands and cut down trees to create a road blockade. The photograph shows a pick-up truck with a hand painted banner. In capital letters it reads: “Total Isolation for Aysén Now.” The “now” is written in red for emphasis. Today I stopped by the store to stock up on food, thinking that the road might be blocked for a while. My friends assured me the blockade was just for tourists.

Despite some voices urging me to fly home to the United States, I decided to come home to the end of the road instead. When we arrived at the town’s new checkpoint, a policeman stepped on the bus and asked the driver, “Is everyone here a resident?” “Yes, just locals.” I gave them my cédula and as I live right next to the checkpoint, I got off the bus. As I was walking away, one of the cops said, “Hey Page, you forgot to give us your phone number!” So happy that she remembered my name, I joked back, saying, “I gave it to you a few months ago and you never called me!”Now that I’m here, I hope I can finish my research, in whatever way might be possible. These three weeks were supposed to be my last break before my final stage of fieldwork, when I was “really” going to get everything done. But things are different now, particularly the connections we make. If we follow the new government rules, not only can I no longer do face-to-face interviews, but we as a community can’t interact with each other in ways we are used to. We aren’t supposed to visit each other, and if so, we have to be in our homes by 10pm. To avoid contagion, we are not supposed to drink mate together or kiss one another on the cheek. Someone kissed me hello the night I arrived and while I said, “We’re not supposed to do that anymore,” I was so grateful for the gesture welcoming me back to town. I see this time as a valuable opportunity to rethink my understandings of connectivity and isolation as I witness a community reconsider a future that was never really challenged before. Whereas there was mostly polite silence at the end of the zonas rezagadas meeting a few weeks ago, I suspect now there will be many more questions.

Cite as: McClean, Page. 2020. “Questioning Connectivity: Life in a ‘State of Catastrophe’.” In “Pandemic Diaries” Gabriela Manley, Bryan M Dougan, and Carole McGranahan, eds., American Ethnologist website, March 27, 2020. [https://americanethnologist.org/features/collections/pandemic-diaries/questioning-connectivity-life-in-a-state-of-catastrophe]

Page McClean is a doctoral candidate in anthropology at the University of Colorado.