Listen to the audio version of this essay here

Dried cheese is not a food one eats quickly. You suck on it, move it around in your mouth, chew it, savor it. Eating dried cheese offers time for stories to unfold. As we ate, Tenzin told me the entire story, even the parts I already knew. She told it in that way you tell a story to someone who was there for it. She told it for confirmation as well as for comfort.

As I write these words, Tenzin is sick. On the day we ate cheese and talked in Kathmandu, she was not. She was healthy; I was healthy; our children were healthy. While we could not then imagine her terminal illness, she could see her future. My children are elsewhere, she said. I can’t get them. I can’t claim them. I have no status. My karma is that I am here alone. What can I do?

[rewind to the day before]

I went through three security gates to get to the room where I heard familiar words. “There is nothing we can do.” I had heard them before in UN offices in India and Nepal. They were words of empathy and frustration, but also of absolution. We are not responsible; there is nothing we can do. I heard them in a room with weak air conditioning on a hot summer day. They were words spoken as only bureaucrats can:

There is nothing we can do for the Tibetan community.

We are here at the request of the government.

It is up to the local government.

If the Nepali government wanted, they could issue identification documents to all Tibetans in a week.

We don’t consider Tibetans stateless because China considers them citizens.

There is nothing we can do.

Tenzin knew I was going to the UN office. Like many others, she looked to the United Nations for justice. Truth will prevail, the Dalai Lama reassures them. Tenzin believed this. She believed that the truth of the situation would lead to its resolution. She believed Tibet would once again be under Tibetan governance rather than Chinese colonial rule. She had faith in the Dalai Lama and hope in the United Nations. Religious and political faith in the Dalai Lama is cultivated over centuries. Hope in the UN is different. It is grounded in a universal humanism that was never truly universal. It is grounded in the belief that injustice will be recognized and addressed. But, China is a world power no country is willing to challenge. And so in UN offices in South Asia, polite civil servants repeat, “There is nothing we can do.”

[exit the anthropologist]

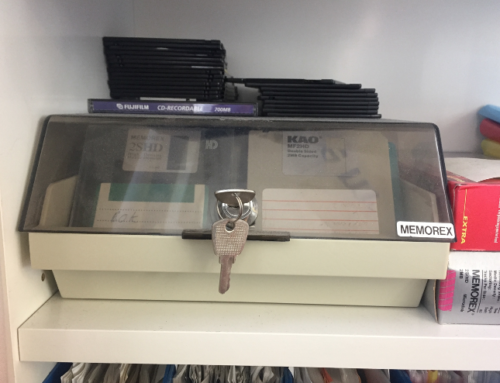

Thermos still life, Kathmandu. Photo by Carole McGranahan.

The next day I went to see Tenzin. We hugged each other and giggled, and I sat down on a carpet-covered bed while she poured us tea. Early morning sunlight filtered into the room through gauzy curtains; incense smoke danced in the breeze. We settled in, catching up on all that had happened since we last saw each other. For much of our conversation, her eyes were wet. Things were not going well. What can I do, she asked. It was a question for which she did not really expect an answer, nor did I have one to offer.

Tenzin was divorced. Her husband had beat her. Back then, domestic abuse was not something refugees could seek help for from anyone other than their families and friends. Things are starting to change, starting to slowly change. Her world is sad, that of a mother separated from her children, of a woman whose life has not gone as planned. Following their divorce, Tenzin’s ex-husband took the kids. He made decisions for them without consulting her. They moved from country to country. What could she do? What rights did a mother have? What rights did a refugee have?

None, it turned out.

Tibetan refugees in India and Nepal have no internationally-secured rights. No country in South Asia has signed on to the UN Convention on Refugees. Tenzin had no political status or rights or documentation. She was in Nepal. Her kids were in India. Her ex-husband was in hiding.

What could she do?

[ ]

In an office somewhere in South Asia, bureaucrats claim no responsibility. There is nothing they can do. Tenzin, no longer in Kathmandu, refused that answer. She left Nepal in hopes of something better, but her children are still not with her. They are on different continents, and she is now sick in a world that continues to push them apart. Tenzin says this is her las, her karma. Actions in her past lives shape her present reality. But karma does not absolve. It includes entanglements. It involves responsibility. She says: tell my story.

Cite as: McGranahan, Carole. 2020. “Karma and Air Conditioning.” In “Flash Ethnography,” Carole McGranahan and Nomi Stone, editors, American Ethnologist website, 26 October 2020, [https://americanethnologist.org/features/collections/flash-ethnography/karma-and-air-conditioning]

Carole McGranahan is an anthropologist at the University of Colorado. She is author of Arrested Histories: Tibet, the CIA, and Memories of a Forgotten War (Duke University Press, 2010).