Each student in the cohort of 15 students I met at Phoenix High1 in central London navigated five different first or preferred languages during the first workshop and throughout our time together (Persian, Arabic, Portuguese, Kazakh, Spanish), six including English. Ranging in age between 11-15 years old, each of them had emigrated to the UK within the previous 6 months and had been labelled by the school with the moniker of “recently-arrived” because of their unsettled immigrant or refugee status. In my first workshop lesson with the children, I introduced them to anthropology, discussing the ways we might understand another person’s life based on the clues in their environments and objects that surround them, and how we might document these. We mapped the classroom and objects around us, and I encouraged them to use any form of notation that might help them to recall what those material clues might mean about the people who use them.

Something unusual happened with this group of students, however. Across the sessions I’ve run in schools since 2021, through this project called Anthropology By Children or “ABC,” this was the only group of students who did not welcome the move away from English. They resisted using drawings and were focused on correctly using the English language, using all the same words, written in the same way. One boy translated words from English into spoken Persian and Arabic to help his classmates, who in turn copied meticulous, identical words from his page onto their own papers.

In this essay, I ethnographically unpack how my methodological approach attempts to make lesser-seen children “present,” drawing lessons from the use of Participant Action Research (PAR) in which interlocutors not only lead data collection but also drive analytic categories through their engagement (Freire 2021; see also Boal 2014). It is my claim that ABC harnesses the underexplored potential of Citizen Science in UK secondary education (Roche et al 2020), an effort that privileges student-experiences as crucial fieldwork data and fosters an auto-ethnographic examination of school-based “social ecologies” perspectives on the spaces, places, people and connectors that extend outward from school and into students’ own communities and lives. It likewise helps young people build their communication skills, their dispositions toward self-advocacy, their perceptions of their own abilities, and their appetites for activistic transformation.

In an effort to include students of all language levels, educational needs, and abilities in the ABC workshop activities—the methods I use are as non-textual as possible, incorporating visual and aural auto-ethnographic techniques to accommodate the students’ lived expertise. I draw on the approach used by the Critical Race Theorists Zahra Bei and Helen Knowler, who use what they call “composite counter-storytelling” as a way to amplify the voices of those who are less frequently heard-from, thus “[enabling] excluded people a chance to be seen” (2023, 231). In the case presented here, however, it could also be argued that within the UK immigration system, which these particular students must actively negotiate, their current worth is perceived to be greatest, by themselves and by others, when they become imperceptible. This tension is essential to understanding “present/presence” as a complex pedagogical category that is worth our anthropological attention.

The UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989) asserts that all students should have an active role in their education, taking part in decisions about them and directing changes when needed (de Leeuw et al 2020). “Pupil Voice,” the agenda which aims to represent young voices in decision-making about them, has been advanced to make this viable. Though the UK’s education auditing body, Ofsted, recently reconfirmed the importance of Pupil Voice representation, children from minorititized groups remain under or unrepresented. As I’ve seen in both the statistics and in the field over 30 months, providing young people with surveys or student assemblies in order to “speak up” without cultivating the skills required to do so can result in children being absent—either literally absent, as with the 1.7 million children who were “persistently” absent from UK schools last year, or metaphorically absent from discourse and dialogue.

As one Head of Schools recently told me: “We’re living through unprecedented problems in schools but using the same tools we’ve had for decades, and they’re not fit for purpose.” The UK is developing different kinds of young people with different levels of related presence in public conversations concerning their health and educational needs. At Phoenix High, the young people were acutely aware of the role English language played in whether or not they were able to “be there,” leading them to cultivate particular personhoods to meet the expectations of others and themselves. This not only determined who they could be in the present, but who they were before, and who they might be in future.

I encouraged Phoenix students to use sketches, colors, and languages used at “home” with their families, as a means to encourage students to tell their stories of what they witnessed in the world. The word “home” is my own gloss; in the 13 weeks I spent at Phoenix, countries were called by their names: Brazil, Iran, Afghanistan, Colombia, Kazakhstan. More than half of the children did not read in their mother tongue because their studies had been disrupted by sudden, crisis-driven flight due to conflict, famine, or other unnamed reasons.

By contrast, what made them a cohort across different year groups, ages, and national backgrounds, was what they communicated and performed together in and about “school.” The classroom space was entirely focused on honing their English language capabilities so they could get better at writing and reading, thereby accessing their wider subject studies. Within this context, the flexibility of the exercises I proposed had visibly stressed them out, as did the pastries and juice provided by the school for the ABC workshop-club sessions. “We’re here to learn, not eat,” said one girl, wondering aloud if the group was being tricked into disclosures of some kind which would be used against them at a later time. Was my aim to report to the head teachers that their will to use English had proven to be weak, abandoned at the first opportunity? Despite my assurances that this was not my agenda, the girl and others around her remained unconvinced.

After one session a teacher explained that one 11-year-old had, only a few days prior, been chased by a local woman who had seen the child emerge from a hotel where recently-arrived families were being housed. The woman screamed racial slurs, brandishing a shard of glass as she ran after the child, until a neighbor tackled the woman to the ground, allowing the child to run through the school gates. I met another young person whose family had been “relocated” multiple times from their local accommodation to what was meant to be a new “home,” only to find they had been sent to a detention center with no available schooling. Each time they turned back to the relative security of their temporary accommodation so that their older child could sit their GCSE exams. Though the local area around Phoenix is labelled as a “we welcome refugees” borough, the tone of local graffiti and stories like these speak to an alternate view. The local area is richly diverse, but this is not to say that it is an area without conflict. Standing up and speaking out are not things these young people appeared inclined to do.

I therefore engaged with the young people through other means: providing pre-cut newspaper and magazine images and asking them to choose four or more images to make a collage. Using this method, they told their stories of things they value, whether in English, or by using home languages, or remaining unvoiced. This was deemed more acceptable, and conversation gradually turned to football and swimming, to the people in their lives, and to their experiences of places they had lived before.

Examples of the children’s collage work. Photo by Kelly Fagan Robinson

Two boys began an animated discussion about Iran, how much they missed being by the sea, opening a small window onto how the boys understood where and who they were now that they were in the UK, compared to where they used to be:

Boy 1: “Me I don’t like to play football […] Me, I like swimming. I have, I don’t know what the name is […] Me I have a cup for swimming […] go to tournaments…

Kelly: Oh you compete?!

Boy 1: Yeah and I… Seven cups […] And I have مدال ]…I don’t know how to say?… [to his friend in Persian] مدال ]…

Kelly: Medals?!

Boy 1: Yeah! I have four 1s and one 2. And seven cups.

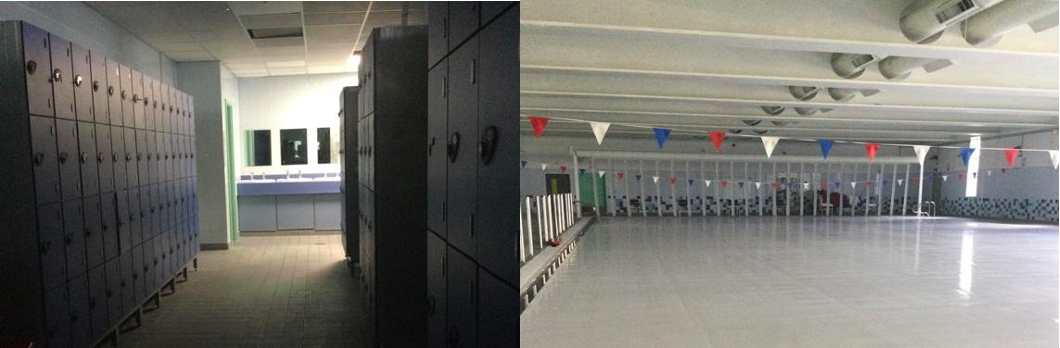

For their final ABC project, the young people were sent into different spaces in their school building to photograph things they valued and things they would like to change. Once the photos were taken, I would overlay audio-recorded narration from our discussions, some in English, others in Portuguese, Kazakh, and Persian. I was unsurprised when the boy with the swimming medals took a photo of the school’s pool facilities—a covered walkway in the adjacent wing of his school building was an Olympic-sized swimming pool.

Images of the empty locker room and covered swimming pool. Photovoice work by Phoenix High Student2

His first photo is of the empty locker room and the second, the pool itself with a large, locked cover over it. The boy explained he had been to in-school swimming lessons since coming to the UK, but he no longer trained or competed. In Iran he had been nationally ranked. His narration over the picture ends with:

“I forget swimming… No I mean, I know how but… I forget swimming.”

As highlighted by the boy’s experience, the children’s audio-photographic archives speak to the challenges in London “now” as well as joys, pains, losses, and gains, referencing the “before” while looking forward toward unknown futures, contingent on their work in the present. In other words, their worlds are multidimensional, complicated and not always articulable in the context of what is expected of them “now,” aligning with Michael Lambek’s discussion of horizons wherein: “acting in the present always supposes orientations with respect to past and future […] They are outer limits, but they are not limitations” (2018, 11).

As we spent time together, the young people began to share more with me about their lives “before,” not in opposition to the world now, but apart-from, the way one might describe a much-enjoyed holiday, separate from “the everyday.” It is through such “invisible things” that the everyday “articulates itself by way of the relationship that their strangeness has with familiarity” (Certeau 1998, 3-4). Repeatedly I was told by different students that if they could be successful at school—for their families and for themselves—if they could become seamless in their English, then they would succeed in their schools and ultimately beyond school. Particularly in their own explanations about why learning English matters, the ambition of fluent language acquisition to gain greater access to UK-based futures is clearly important in this context. Learning English opens doors for these young people to establish peer friendships and relationships with teachers, as well as to gain greater clarity about the newer spaces they now inhabit. But as the young people’s adherence to linguistic and behavioural sameness takes hold, blending in as a strategy for continuance also serves to flatten out the persons they might once have felt themselves to be, at least in the ways they present to others.

A few weeks after we completed the project, we presented the work to a room full of the school’s teachers, including the boy’s closed-pool photograph and recorded commentary. As the teachers watched the film, the two PE coaches sat up straighter when listening to the boy’s past swimming achievements. One turned to the other, audibly asking: “Did you know?” The other man shook his head: “No.” Someone called out that they needed to get that boy onto the swim-team, which was followed by murmurs of assent. It is one small instance in which listening to multidimensional humanness can shift perceptions of who children are now, what they have been, and what they might be, rendering them newly present.

Notes

[1] School name anonymised

[2] Images and ABC Copyright Robinson (2023)

References

Bei, Zahra, and Helen Knowler. 2022. “Disrupting unlawful exclusion from school of minoritised children and young people racialized as Black: using Critical Race Theory composite counter-storytelling.” Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties 27(3): 231-242.

Boal, Augusto and Charles A. McBride. 2014. “Theatre of the Oppressed.” In The Improvisation Studies Reader. Edited by Rebecca Caines and Ajay Heble, pp. 79-86. New York: Routledge.

De Certeau, Michel, and Pierre Mayol. 1998. The Practice of Everyday Life: Living and Cooking, Volume 2. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

de Leeuw, Renske R., Cathy Little, and Jonathan Rix. 2020. “Something needs to be said–Some thoughts on the possibilities and limitations of ‘voice.’” International Journal of Educational Research 104(101694): 1-5. London: Elsevier Ltd.

Flynn, Paula, and Nóirín Hayes. 2021. “Student Voice in Curriculum Reform: Whose Voices, Who’s Listening?” Curriculum Change within Policy and Practice: Reforming Second-Level Education in Ireland: 43-59. London: Palgrave Macmillan Cham.

Freire, Paulo. 2021. Education for critical consciousness. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Lambek, Michael. 2018. Island in the Stream: An Ethnographic History of Mayotte, Toronto: University of Toronto Presshttps://doi-org.ezp.lib.cam.ac.uk/10.3138/9781487519049

Lundy, Laura, and Alison Cook-Sather. 2015. “Children’s rights and student voice: Their intersections and the implications for curriculum and pedagogy.” The SAGE handbook of curriculum, pedagogy and assessment 2. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications Ltd.

Kelly Fagan Robinson is a Leverhulme Early Career Research Fellow, Medical Anthropology Examiner and Lecturer for the Health, Medicine and Society MPhil and in the Department of Social Anthropology at the University of Cambridge. Her Leverhulme ECR Fellowship project (2021-2024), titled “Communication Faultlines on the Frontlines,” tests the limits of communicating need and deservingness of support between people who have little common ground. Her work covers a broad base of anthropological and interdisciplinary research in semiotics, language, and epistemic dissonances within institutional spaces in the UK and internationally.

Cite As: Robinson, Kelly Fagan. 2024. “The Present as Legibility”, In “Back to the Present” edited by Timothy P.A. Cooper, Michael Edwards & Nikita Simpson, American Ethnologist website, January 26 2024, [https://americanethnologist.org/online-content/collections/back-to-the-present/the-present-as-legibility/]