When I wrote this sentence, the former president of the United States, Donald Trump, had just had his fingerprints taken. The pundits on the news channels are both salivating at the historical importance of this unique event and speculating about the implications for the 2024 US presidential election, for which Donald Trump declared his candidacy some time ago, in November 2022, well before anyone else. The new consensus seems to be that—while being arrested will hurt him in the general election—it helps his campaign to become the Republican party nominee—supercharging it, as one reporter put it. This view is presented as something of a surprise, most reporters having assumed his power to be on the wane since the disastrous showing of Trump-backed candidates in the mid-term elections in November 2022.

As part of my ethnographic research into political gambling, I have been betting against Donald Trump for 2024 since September 2022, at which point he was the favourite. I have been betting for Joe Biden since sometime earlier than that; he was running in third at the time and is now favourite. If you want to make a bet on politics in the UK, where I do fieldwork (it is quite different to the US), you can walk into a betting shop on the High Street and place a bet with cash, use an account online, or do so over the phone. You can also choose whether to bet against the provider at the “odds” they offer (a £3 return for a £1 bet represent odds of 2-1, i.e., £2 for winning, plus your money back) or you can bet against another bettor on a kind of market for gambling, called a betting exchange. This is considered a more sophisticated platform; it can be confusing to navigate, but it also comes with some benefits. For example, on betting exchanges like the one that most of my research participants and I use, you can trade in and out of positions as the market moves.

Odds are futures captured and put on sale today. Normally considered a prospective activity, the presentism of gambling is often neglected. Political gambling specialists develop “theses” that anticipate future political events and their outcomes, calculating what they consider the correct odds of an outcome (say 2-1) and compare it against current market odds (say 3-1). If the odds on the market are different enough, they consider these to be misprices, which can be exploited by betting either for the outcome (as in this example) or against them (if the numbers were reversed). This is a future-oriented activity, but it hinges upon an accurate understanding of the present. Are the British public fed up with the political fallout of Britain leaving the European Union? Are polling figures still skewed by respondent bias? Is President Biden feeling his years? Future profits hinge on up-to-the-minute understanding of the implications of now upon the future, and the ability to act upon them. As the editors of this collection suggest implicitly, the present is not merely the place where the future lives in our imaginations; the future is subject to the present’s accumulated economic and power structures, including both its manipulatory power and its poverty of understanding. Political gamblers aspire to be a small percentage more accurate than the present’s-eye-view.

It has been my betting thesis that the markets have priced Biden incorrectly. As the incumbent, and for other reasons too, his odds should always have been much shorter (read: more likely) than they were in the last year. This mispricing was especially egregious because part of the long odds (read: perceived unlikelihood) was based on doubts as to whether Biden would run—but Biden himself said he would run, and nobody could actually stop him. My thesis was not that Biden will win a second term. That depends a great deal on who his opponent is along with macro-forces. My point is that I don’t have to believe in Biden and be right to be successful, I only need to anticipate a market correction once punters have realised that the current consensus on likely results is weighted incorrectly and then trade out after the market corrects.

My bets against Trump were poorly timed. Back in the immediate aftermath of the midterm elections, Florida Governor Ron DeSantis was looking dominant, and Donald Trump was losing the support of Fox News. My thesis had been that Trump would fade and perhaps leave the race. Instead, he has steadily risen in the odds since the New Year. Given I am confident that Trump cannot win the presidency should he win the nomination, I am not going to trade out of my position at a loss because I am confident of a small profit eventually. However, my thesis has proven incorrect in the medium term, locking some of my investment down. And here I am self-consciously adopting the language of my interlocutors.

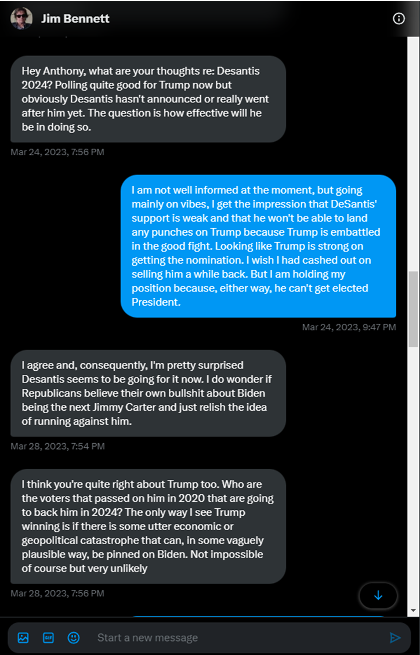

My research participant Jim, a Canadian PhD student, discussed our positions over Twitter messenger over the past few weeks:

Screenshot of discussion on political gambling, reproduced with permission.

Such is the world of political betting. We went on to think up a series of potential catastrophes. As you can tell, Jim and I tend to hold similar positions this cycle, although he had thought that Trump was more likely to win than I did.

It seems obvious that gambling is an activity oriented toward the future. Simply put, one commits a valuable to an event whose outcome will be revealed in the future, with the result affecting the rate of return. Political gambling, with its focus on human-centric events that are consequential at the societal scale, is no outlier in this respect. For those who participate regularly in the activity, there is a special satisfaction in predicting the future of the things that matter. This kind of speculation attracts a certain kind of individual. Political gamblers are overwhelmingly male, they tend to be tax lawyers, heads of university departments, entrepreneurs with PhD’s. In other words, highly educated men with an itch to scratch. Others are specialists at gambling, professional gamblers who see politics as a field in which there are especially high levels of value to be taken (read: mispricing or, as they also put it, “mug money,” from the people a US gambler might call “fish”). Some even claim the mantle of the real political experts because they can prove they saw things coming. And you do see more and more of them in the media around elections.

Their mode of understanding is inimical to anthropological sensibilities, if not to anthropologists’ realities. When we produce research, the present is often presented as best understood in its sprawling ethnographic minutiae, delivering insight that other disciplines cannot. Anthropological presents are more often a ripple in the long durée (across which humanity acts as it has and will), or a moment within an ongoing melee of structural forces. Efforts to arbitrate between the world as it is and as it will be surface more in departmental budget meetings and faculty appointment committees, not to mention impact case studies and calls to action. What would a more opportunistic anthropology of this moment look like? How might a speculative anthropology operate effectively in practice? Could political gamblers be a long-odds source of inspiration?

Anthropology tries to comprehend a human world that cannot fully know itself. By looking at future-arbiters such as political gamblers, who work very hard to cultivate an understanding 10% better than the consensus view of now and then act, perhaps some of us could make our voices more relevant to a present that is obsessed with the near-term future. But how? Gamblers have the advantage of expressing their opinions through pricing. I sense that would be a step too far for most anthropologists, including me, but I think we could start making some predictions and then get better at them.

Anthony J. Pickles is an Assistant Professor of Social Anthropology at the University of Birmingham. His work on gambling, economy and politics are ethnographically grounded in Papua New Guinea and, latterly, in the UK and US. Money Games: Gambling in a Papua New Guinea Town (Berghahn, 2019) is his first book.

Cite As: Pickles, Anthony J. 2024. “Gambling on the Present”, In “Back to the Present” edited by Timothy P.A. Cooper, Michael Edwards & Nikita Simpson, American Ethnologist website, January 26 2024, [https://americanethnologist.org/online-content/collections/back-to-the-present/gambling-on-the-present/]