Coming up the escalators from the Potong Pasir MRT station on a humid Tuesday evening, I walk ahead through the decks of the public housing blocks that surround the station and past the food court. The mixed aromas of thosai and sambar, roti prata, curry laksa, and char kway teow permeate the air to the sounds of clattering woks, trays, and plates and the murmurs of friends, neighbors, and families gathering to eat dinner, chatting in Tamil, Hokkien, Malay, Mandarin and Singlish. Behind the food court, I turn into a five-foot way, which is immediately quieter, and I spot and greet Hema, who is buying two bags of bright red and yellow flowers, one for her and one for me, for our visit to the Hindu temple across the street.

Buying flowers. Photo by the author.

We step back out and cross over to the temple on the other side of the street, leaving our slippers on the metal racks bordering the temple walls, and using the cold-water hoses to wash our feet of the day’s residues.

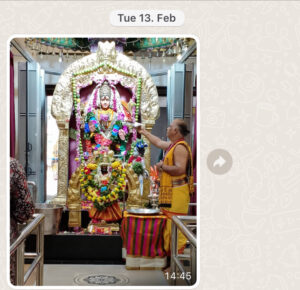

Hema guides me to the black Ganesha statue in the entrance area of the compound and instructs me to place some of my flowers on the deity. The soundscape is suddenly, dramatically louder, with bells ringing, priests chanting and the high-pitched wails of the nadaswaram instrument, signaling the crescendo of the ritual going on inside. She leads me into the temple to see the priests blessing the goddess Durga, while devotees put their hands together in prayer. Hema took out her mobile phone to take a photograph of the goddess at her most powerful, which she will later send to her contacts on WhatsApp as a gesture of care and connection, as she does every week. She urges me to take a picture too.

WhatsApp Blessings. Photo by the author.

Hema is now 64 years old and has been working in Singapore for the past 36 years as a domestic worker on the most restrictive work permit—one that requires her to live in a small room at the back of her employer’s flat, that denies her the right to family reunification, to social security, and to permanent residence or citizenship. As a “temporary migrant,” she is a transient, invisible presence in Singapore’s national and social landscape, despite her long decades of work. The state requires that she returns to her country of origin (Sri Lanka) in retirement. This designation of her temporariness is at odds with her long-term practices of home-making and her own sense of belonging in Singapore. Raised a Buddhist, Hema’s religious practice became more syncretic over the years through her diverse encounters in Singapore’s multi-religious spaces. She became drawn to the Hindu goddess Durga: a goddess, in Hema’s view, with shakti, symbolic of women’s power and that which gives her creative energy, strength, and protection in dealing with the precarity of life as a domestic worker in Singapore. Hema visits the temple weekly, with Durga accompanying her routines of cleaning, marketing, cooking, and caring for the aging grandmother in her employer’s family.

At the end of our temple visit, Hema suggests that we sit down for a short while. She is feeling a little tired and I can see beads of sweat form on her eyebrows as she pulls out a handkerchief to wipe her face. Hema sits on a plastic chair, and I sit cross-legged next to her on the stone floor of the temple. From the ground looking up, I observe the different people around me: a young woman on her own dressed in an elegant salwar kameez, intently praying for something in her life; a multigenerational family doing the rounds; two migrant men finding a moment of peace at the end of a long day of their physically strenuous labor. Locals and migrants who are normally kept apart by Singapore’s strict laws share this space of spiritual transcendence in a moment when the distinctions between them—and ideas about who belongs and who does not—matter less. My own experience growing up in Singapore in a Tamil-Hindu family involved occasional visits to the temple before school exams during which I would follow a set of instructions from my mother. Many years later, I was similarly following Hema’s lead. She regularly suggested meeting at the temple but I felt inadequate accompanying her on these visits, expected as I was to know what to do, yet failing to bring the right flowers or to embody a temple-going habitus. Meanwhile, Hema, a migrant woman who did not self-identify with any one religion, was far more synchronized with the rituals in this space than me. It was revealing of the arbitrariness and contradictions of state demarcations of difference and belonging, one that indifferently determines Hema as “foreign” and thus unable to stay on in her later life years.

Hema told me that she was not yet ready to return to Sri Lanka and often said that she wanted to stay “two more years,” the present more comforting to her than the unknowns of the future (Pauli 2023). She still had to save money for older-age and was worried about what she would live on. Neither the Singapore nor the Sri Lankan state provides her with a pension despite her decades of care labor—a reminder of the gendered devaluation of care labor around the world and the lack of future security for women like Hema whose work has not been valued as work. She will further return to an economically challenging situation in Sri Lanka, the country recently hit by economic and political turmoil. Her remaining stay in Singapore is contingent on her clearing a medical check-up every two years. Her rising blood pressure (and living through the COVID-19 pandemic) has made her anxious about her health and “fitness” to stay on as a worker, her aging body dispensable to the economic logics of the state. Every time I would return to Singapore from Germany to meet Hema, she would ask: “How do I look, do I look run down?” She would then state: “I feel okay. I am still strong.”

Hema worries about how she will retain her autonomy upon her return to Sri Lanka and about leaving her lifeworld of plural encounters and experiences in Singapore behind. Hema does not have children of her own and her parents have passed away. She will return to her village in western Sri Lanka to be with her sisters and nieces, living in her big house constructed over the years with her remittances. The most important spaces to her are the kitchen, where she imagines herself cooking for others; the altar, for which she has been gathering deities and statues from Singapore; and her peaceful garden with its mango trees and birds.

Hema’s house in Sri Lanka. Photo by the author.

On her own care in later life, Hema wonders aloud, “when you are older, who will take care? That is what I always pray for. Don’t give anyone trouble. Actually, we say karma, you know? What you do bad, you will get back. If you always do good things, your life is better and you don’t suffer.” In addition to her ethical practice (see also Gamburd 2021), she has saved up some gold over the years as her emergency fund and has recently opened a savings account as she realized that she needs to save more money for her retirement.

Hema’s uncertainties about the future as an aging domestic worker are not unique in Singapore. Many other migrant domestic workers from the Philippines, Indonesia, and India are similarly denied the right to choose where to spend their old-age, and are left out of later-life social protection schemes. Kin relations as a source of future social protection are not always reliable. Some women are confident in finding support from the next generation but many others are wary of the emotional challenges of reconnecting with kin after decades apart and how this might affect their care arrangements. There are different strategies that emerge to deal with these anxiously-anticipated futures—some financial, others ethical and spiritual.

Amidst all the uncertainties ahead of her, Hema chooses to confront her future spiritually as a means to make her later life years meaningful (Kavedžija 2018). Alongside her visits to the Hindu temple, she volunteers in a clubhouse for domestic workers and occasionally helps to cook and clean at the Sri Lankan temple, finding moments to sit under the Bodhi tree. “Any worry I have,” Hema says, “I come and sit under the tree and it goes away. I feel peace.” These activities together form her response to the ruptures and displacements that sit on the horizon. They fuel her imaginaries for a good future as she approaches retirement, offering a tentative bridge between her life in Singapore and her aging future in Sri Lanka.

References

Gamburd, Michele. 2021. Linked Lives: Eldercare, Migration, and Kinship in Sri Lanka. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

Kavedžija, Iza. 2019. Making Meaningful Lives: Takes from an Aging Japan. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Pauli, Julia. 2023. “Before It Ends: Aging, Gender, and Migration in a Transnational Mexican Community.” In Aspiring in Later Life: Movements Across Time, Space, and Generations. Edited by M. Amrith, V.K. Sakti, and D. Sampaio. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

Megha Amrith leads the Max Planck Research Group “Aging in a Time of Mobility” at the Max Planck Institute for the Study of Religious and Ethnic Diversity in Göttingen, Germany. Her research interests are on care, migrant labor, aging and wellbeing. She is author of Caring for Strangers: Filipino Medical Workers in Asia (2017, NIAS Press) and co-editor (with Victoria Sakti and Dora Sampaio) of Aspiring in Later Life: Movements Across Time, Space, and Generations (Rutgers University Press 2023). She is now writing a short monograph on the futures of aging migrant labor.

Cite as: Amrith, Megha. 2024. “Ruptured Home-Making as “Temporary” Aging Migrants in Singapore.” In “Aging Globally: Challenges and Possibilities of Growing Old in an Unsettling Era”, edited by Magdalena Zegarra Chiappori, American Ethnologist website, 7 August 2024. [https://americanethnologist.org/online-content/collections/aging-globally/ruptured-home-making-as-temporary-aging-migrants-in-singaporeby-megha-amrith/]