As an anthropologist I’m better trained in critique than in fantasy, and so I asked Bassem Abu Gweily, a poet and migrant worker, for inspiration. He wrote:

“The first thing that crossed my mind was Don Quixote on his travels, or Che Guevara on his trip… and the journey of the Divine Comedy. This kind of things, and for example Invisible Cities and If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler by Calvino, and the travels of the Friends of God (awliya’ Allah), the people of the step. And there is the movie Interstellar…”

This is the kind of travel that I would like to see possible in a better world after Covid-19. However I’m not a poet; mine is a scientific fantasy bound by certain premises, of which there are three – two conservative, and one radical:

- First, laws of physics remain the same. We cannot have all the good things for all the people all the time because our economic activity inevitably depletes natural resources on which the survival of Earth’s ecosystem relies.

- Second, humans will not turn to angels. We continue to be capable of cooperation and prone to competition alike. Our search for justice remains paired with our striving for privilege. Our sense of solidarity will still cast shadows of racism and other prejudice. Inequalities, conflicts, and double standards will be part of our better world.

- Third, and this is the radical assumption, at the end of the Covid-19 pandemic, humans will miraculously reach a moment of shared long-term insight of the situation we all are in, and join in a unique collective act to establish a world in which our constructive potentials of cooperation, solidarity, permissiveness, and care are utilized better, and our destructive potentials tamed. A miraculous solution to our economy’s fateful dependency on growth is found, and we transition to an age of sustainable economic stability wherein even the poorest have enough to eat, and the wealthy may enjoy modest comfort but no excessive luxury. Don’t ask me how.

In the new world, there is no discrimination between travellers. There are no visa regimes and no border controls. Everyone can move and settle as they want. The settlement of large populations in a new location requires a negotiation and agreement with the previous inhabitants of the area, but that is not needed very often, because people are rarely compelled to move in great numbers. Migration is easily available, but is no longer an urgent necessity because inequality throughout the globe has been somewhat reduced and is geographically more evenly spread than it was before Covid-19. While there are richer and poorer, more and less powerful people in all countries, no country is richer or poorer than the other. The same is true for villages and cities. Village life is more vibrant and pluralistic than previously. Not all rural people appreciate the plurality, but they do appreciate that their children no longer have to move to the cities or abroad in search of opportunities. Big cities are less dynamic and cosmopolitan, but also less stressful and more affordable to live in than previously.

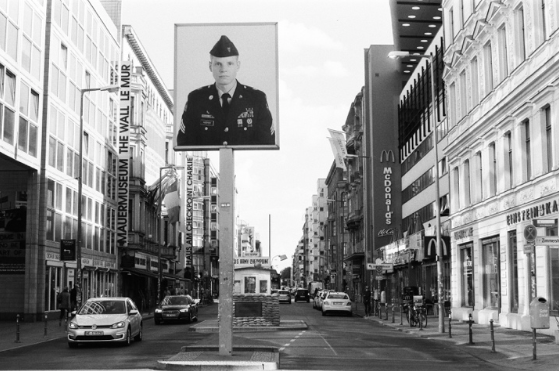

At Checkpoint Charlie where the Berlin Wall once stood, borders and controls are a memory from the past, and there are no tourists. Photo by Samuli Schielke 27 May 2020.

Political asylum is easily and universally available, but in not much demand because labor migrants are no longer forced to use the asylum system as a detour around visa regimes like they were previously, and because the relative equality of economic conditions around the world ensures a relative similarity of political conditions. Since conflicts still exist, refugees still exist, but one part of the miraculous reorganization of global society is that wars, when they happen, are short, limited, and conclusive, so that people displaced by them can return to their homes after weeks, or months at most.

But while everybody can travel, there is discrimination regarding the kinds, means, and speed of travel. Due to the great ecological damage it causes, high-speed long-distance travel is restricted to few uniquely important purposes, to which I return below. At the other end of the spectrum, travelling on foot, bicycle, and the like is free and unrestricted (and some amends are made for people who are disabled or sick). For migration, slow but long-distance means of travel such as trains and ships are available, allowing safe and comfortable passage but discouraging long-distance commuter lifestyles. Private cars are available for short-range transportation if they are more efficient than rail, busses, and cycling (they don’t even have to be electric, if there are not too many of them).

Long-distance tourism is abolished. Leisure outings over short distances on foot, bicycle, rowing boat, regional train, or the like are easily available and very popular. Business travel is replaced by online meetings (which we don’t like, but they fulfill their purpose). Business travel is in less demand anyway since the localization of inequalities makes it no longer profitable to produce and transport goods around the world just because salaries are lower on the other side of the globe.

Some means of travel, however, are so important that for them more wasteful and speedy means of transportation are available.

Dante’s journey through Hell, Purgatory, and Heaven; Marco Polo’s stories of strange, mind-bending communities in Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities; and the travels east and west of the Mediterranean by Muslim mystics (the Friends of God) who would become the founders of Sufi paths in the Middle East, together stand for travel for the sake of spiritual and imaginative learning and discovery. Such travel is not about literally walking through the afterlife or conversing with Genghis Khan; instead it shares the crucial feature of openness for new, unknown, invisible knowledge and experiences without which we would only be half human. Open-endedness is its most important characteristic. The Friends of God embarked from Andalusia and Morocco to Mecca on journeys that lasted a lifetime, for most of them either died or settled along the way (a few of them in Egypt)1.

The Hollywood science fiction movie Interstellar stands for scientific study and research, especially of the kind that is crucial for planetary survival. Scientific travel in this sense is obviously not about attending conferences or job talks. The journey to the stars in Interstellar lasts literally longer than a lifetime and involves a dip into a black hole. Our scientific travel won’t be quite that adventurous (human space flight probably won’t be within the means of our ecologically limited energy budgets, and on visiting black holes, see the first premise above); again, what matters is open-endedness. (On this issue, I have a selfish interest, for as an anthropologist, I could be eligible to book a plane ticket every two or three years or so to embark on fieldwork where I may learn things that I could not otherwise imagine.)

The travels of Che Guevara, as recorded in The Motorcycle Diaries and later in his travels as a professional revolutionary, represent travel for urgent political, activist, and societal issues. Although most people now are mobile mainly over short distances, the problems we face are global, and require alliances and solutions that connect people around the globe. Guevara did not board a low-cost air-carrier, but embarked on an uncertain adventure upon motorcycle, hitchhiking, and a raft, among others. Later when he gained access to speedier means of travel, his journeys became more dangerous, and eventually got him killed. The willingness to take such risks are now a requirement for political travel.

Safety and certainty are features of short-range or slow travel, contributing to the safety and certainty of our ecosystem’s survival. The privilege of range and speed is given to risky, unlikely, and open-ended journeys – travel that is like the beginnings of which Calvino’s novel If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler consists, one beginning leading to another beginning, never coming back to the previous story.

The highest, and only unlimited form of travel is therefore that of Don Quixote: journeys of poetic madness that lead to nowhere in particular, and by so doing give geographic contours to humanity’s capacity to dream beyond and against utility. The world’s only private jet is reserved for Don Quixote and Sancho Panza. But since they prefer wandering about the Mancha riding Rocinante and Sancho’s donkey, the plane remains parked on the tarmac waiting, ready to take off upon their request.

Notes:

[1] The Friends of God were also reputed to know a miraculous, energy-free way of travelling vast distances in a single step. But since it is not in line with the first of the two conservative premises of my utopia, I am for the time being assuming that it will not be widely available.

Acknowledgements: Thanks are due to Asmaa Essakouti and Bassem Abu Gweily for inspiration and feedback.

Cite as: Schielke, Samuli. 2020. “Travel: A Post-Covid-19 Fantasy.” In “Post-Covid Fantasies,” Catherine Besteman, Heath Cabot, and Barak Kalir, editors, American Ethnologist website, 27 July 2020, [https://americanethnologist.org/features/pandemic-diaries/post-covid-fantasies/travel-a-post-covid-19-fantasy]

Samuli Schielke is a senior researcher at Leibniz-Zentrum Moderner Orient, Berlin.