The structure, as viewed from the embankment of the Sava river.

As one approaches the city of Zagreb by car from the south, one’s eyes are drawn to a large new shopping centre and a sports stadium on the right side of the road. One could easily miss the large, unkempt green space on the left, where a grassy slope, opening up gently towards the Sava river, almost hides a large structure stretching out parallel to the embankment.

Approach from the front.

Once planned as an ambitious new hospital for the city of Zagreb, the building is both unfinished and dilapidated, even though hospital space remains in high demand. Indeed, healthcare has come under increasing strain in post-socialist Croatia (Zrišćak 2007).

Approach from the front.

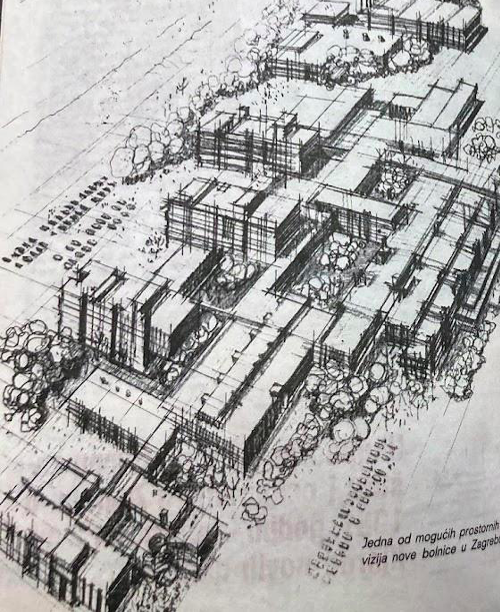

The original plans for Nova Bolnica (New Hospital) show a large, airy and modern building, 700m long and up to 200m wide in places, providing space for a polyclinic, diagnostic and inpatient wards with a capacity exceeding 1000 hospital beds, as well as state-of-the-art facilities for teaching and research (Sveučlišna Bolnica Zagreb 1995).

Plans for Nova Bolnica from the referendum pamphlet. Image source: Zagrebački za zdravlje, 1982.

As one wanders through the empty skeleton on sturdy pillars today, however, broken glass crunches underfoot. Unfinished metal stairwells have no landings, instead offering vertiginous vistas up and down the building. Unguarded elevator shafts stand agape, offering a remote glimpse into the shadows of the underground parking. The emptiness has a “sensual dimension” (Dzenowska 2020, 11). The damp smell, the soft moss growing on concrete under the leaking giant roof of the entrance space, the wind blowing through unglazed inpatient wards, the crunching of the shattered glass.

Inside.

Temporalities of Care

“[P]ractices of care contain within them ‘multiple chronologies’ that refuse easily to align” (Cook and Trundle 2020, 181).

The case of Nova Bolnica invites reflections on intersections of intimate care with healthcare systems and infrastructures. The vision of care in question is not a care in the here-and-now, but a caring on a collective scale: of citizens for one another, and for others to come. This necessitates a perspective that extends beyond the immediate interaction between the carer and the cared for, linking the past, the present and the future, but also—perhaps most importantly—the past futures that haunt us. These multiple temporalities stand in an uncomfortable relationship, as collective hopes for better and more accessible care are frustrated and turn to disappointment.

Waiting room.

Spectres of Socialism

“The world has more than one age” (Derrida 2012, 96).

The construction of Nova Bolnica was largely funded by contributions from the citizens of Zagreb through an income sacrifice scheme. A glossy vision of a cutting-edge new hospital offering high quality care in the region was foregrounded in the information brochure prepared ahead of the 1982 referendum, when Zagreb’s residents voted by an overwhelming majority for the self-contribution (samodoprinos) scheme, agreeing to commit 1.5% of their income over the coming five years to finance the construction. A second referendum was held in 1987, extending the income self-contribution scheme for another five years (Večernji list 2020).

Sharp vision.

Information materials for the original referendum, along with an overview of the insufficient hospital capacity that marked the current healthcare situation, featured some of the proposed architectural sketches of the hospital under the heading “contemporary structure and experienced staff.”

After 1992, with the change of government, the influx of money from self-contributions stopped. Sometime after the 1994, the unfinished hospital was declared to be “in liquidation.” Despite attempts to direct further funds to the construction by several later governments, including as recently as 2019 (Nadilo 2014), Nova Bolnica continues to decay.

A Past Future: A Lifetime

“Time is always a social metric” (Rapp 2020, 256).

Professor M told me that many of the brightest young medical doctors who were in residency training at the same time as him, toward the end of the 1980s, were accepted onto the program as the future staff for the new hospital. Over time, they found employment elsewhere. Many have now reached their retirement age.

Temporalities of care span life-courses, national histories, and political systems. These are set against increasingly long patient waiting times and long shifts endured by healthcare professionals in healthcare systems under strain.

Once referred to by citizens as “our” new hospital, Nova Bolnica now occasionally figures as a promise in election speeches. Not fenced off and seemingly open to passersby, the emptiness of the space and the sturdy concrete structure stand in uneasy tension, a phantom of a past future that never materialized–a material structure of disappointment. A “past future” is a vision of the future at some point in the past, often ephemeral, but very palpable in this particular example.

Rear view.

Structures of Disappointment

“For there is no ghost, there is never any becoming-specter of the spirit without at least an appearance of flesh, in a space of invisible visibility… The spectrogenic process corresponds therefore to a paradoxical incorporation”(Derrida 2012, 157).

In their work on health inequalities in US states that opted out of Medicaid expansion, Mulligan and Brunson (2020) describe resentment as lived and built into the law when it was exclusionary, but also when it was seeking to accommodate vulnerable groups (then, seen as an unfair burden on others). They explore the affective discharges of those institutions, public policies, and programmes that reflect and perpetuate distrust among people of different racial and class backgrounds and reproduce racial hierarchies (Mulligan and Brunson 2020, 320). They draw on Raymond Williams’ idea of “structures of feeling,” referring to the enduring qualities of sentiment that mark a particular moment and those emerging ideas that diverge from hegemonic worldviews, but they also suggest that the feelings themselves influence and structure the surrounding world.

Structures of resentment thus have a temporal quality: they are enduring, with effects that unfold over time. In the case of Medicaid, means testing relies on figures such as projected income, which is particularly challenging for people in precarious employment, leading to frustration and resentment (Mulligan and Brunson 2020). Mulligan and Brunson show how this structure of feeling, in turn, feeds into healthcare policies, ever further eroding the support afforded through the healthcare system.

In the case of Nova Bolnica, the structure of feeling appears to take on the physical form of a towering carcass of abandoned infrastructure. Rather than an abstract process of ruination, it exists as a visible monument of a future that failed to materialize. Its material presence makes the hauntings no less troubling, especially for those who subsidized the building process, and had felt each brick and pane of glass was “ours.” Writing about socialist architecture, Martinez complicates the discourse of ruination by pointing to the afterlives of decaying buildings, like Linnahal in Estonia which, in its abandonment, took on a new social life among the local youth. He suggests the idea of maturing, as opposed to ruination: “Mature buildings possess a particular transgressive energy, deconstructing normative spacings and condensing fragmented situated stories. They are containers of meaning (Bevan 2006), keeping invisible memories alive, reflecting multiple contested histories and plural narratives” (Martinez 2018, 107). Unlike Linnahal, with its incomplete disposal, Nova Bolnica never fully came into being. Its presence embodies a vision of care that had not materialized, its solid walls in contrast with its official status “in liquidation.”1

Moss in the parking lot.

Feelings of disappointment and resentment in a society such as Croatia span a range of apparently contradictory positions: the inaccessibility of the services funded through central and obligatory health insurance, as embodied in dangerously long waiting times and overstretched resources and overworked staff; and the inaccessibility of private healthcare, which due to its high cost remains out of reach for many. This abandoned structure captures the peculiar situation in Croatia today, but it also resonates with a far wider affective climate of concern, as the ruination of post-war universal healthcare regimes loom large over Europe, the uneasy sense of concern exacerbated in places where population aging places pension systems in peril.

Phantom of a Past Future

“A ‘hauntology’ requires that we address the complex processes through which traumatic dimensions of contested historical experience are simultaneously kept hidden from view and made visible” (Good 2020, 419).

In contrast to the ghosts haunting the “shadowside” of hospitals (Varely and Varma 2021), this case does not represent the shadow of a tortured past or some colonial trauma (Street 2018), but rather lost hopes and ambivalent affect. For not only did the socialist vision of a better and more accessible healthcare for the city fail to materialize in the post-socialist transition, but the expectations and hopes pinned on the social order continue to disappoint many (see Greenberg and Muir 2022).

Neither open nor closed.

The structures of disappointment, affective and material, ominous and discomforting, nevertheless offer a reminder of almost forgotten expectations: of a different possible future, and a more expansive vision of care. Hidden from view, these disappointments remain unaddressed, if not repressed. It might be time to bring them into view; perhaps their disquiet can be transformed into resistance or hope.

Photographs by Iza Kavedžija. All rights reserved.

Notes

[1] This paradox is one of the themes taken up by the artwork by Borut Šeparović and MONTAЖ$TROJ In Formation In Liquidation. See https://montazstroj.hr/en/projekti/under-establishment-under-liquidation/

References

Cook, Joanna and Catherine Trundle. 2020. “Unsettled Care: Temporality, Subjectivity, and the Uneasy Ethics of Care”. Anthropology and Humanism 45 (2): 178-183.

Derrida, Jaques. 2012. Specters of Marx: The State of the Debt, the Work of Mourning and the New International. London: Routledge.

Dzenovska, Dace. 2020. “Emptiness: Capitalism without People in the Latvian Countryside.” American Ethnologist 47(1): 10-26.

Good, Byron J. 2019. “Hauntology: Theorizing the Spectral in Psychological Anthropology.” Ethos 47(4): 411-426.

Greenberg, Jessica and Sarah Muir. 2022. “Disappointment.” Annual Review of Anthropology 51: 307-323.

Martínez, Francisco. 2018. Remains of the Soviet Past in Estonia. London: UCL Press.

Mulligan, Jessica and Emily Brunson. 2020. “Structures of resentment: On feeling—and being—left behind by health care reform.” Cultural Anthropology 35(2): 317-343.

Nadilo, Branko. 2014. “Nikad završena sveučilišna bolnica u Zagrebu. Megalomanija i “bolnica” na kraju grada”, Građevinar 8/2014: 773-781.

Rapp, Rayna, 2020. “Afterword: Unsettling Care for Anthropologists.” Anthropology and Humanism 45(2): 255-259.

Street, Alice. 2018. “Ghostly Ethics.” Medical Anthropology 37(8): 703-707.

Varley, Emma and Saiba Varma. 2021. “Introduction: Medicine’s Shadowside: Revisiting Clinical Iatrogenesis.” Anthropology & Medicine 28(2): 141-155.

Zrinščak, S., 2007. “Zdravstvena politika Hrvatske. U vrtlogu reformi i suvremenih društvenih izazova”. Revija za socijalnu politiku 14(2): 193-220.

Image source: Zagrebački za zdravlje, 1982.

Iza Kavedžija is an Assistant Professor of Medical Anthropology at the University of Cambridge, working on issues of aging and wellbeing.