How do survivors tell their stories of sexual violence? How should we listen? And why does it matter that we do? As a PhD student at the University of California, Santa Cruz, my ethnographic research over the past six years has entailed listening to survivors on campus in my multiple roles as an interviewer, a survivor advocate, an educator, and a student activist.

Anthropology has long situated witnessing as a practice of care (e.g. Behar 1997; Daniel 1996; Das 2006). This matters both as an object of study and a praxis of writing ethnography. Shedding light on violence enables the possibility for critique—for seeing how power works structurally and differentially through gendered and racialized bodies. Yet, I aim to heed the calls of Black feminist and critical disability scholars to tend to the “uncertain line between witness and spectator” (Hartman 1997, 4) and uplift stories not only of violence, but also survivance. In this short essay, I propose that we must expand our capacities for witnessing fragmented stories by attuning to survivors’ articulations, the form of their narratives, and their aspirations for speaking out.

The imperative of storytelling

In April 2017, during my first year at UCSC, I attended the campus’s annual Take Back the Night (TBTN) event. Over 100 students attended the march through campus, shouting slogans such as “Shatter the silence / stop the violence!” We ended at the Oakes community center for the Survivor Speak Out. The keynote speaker, Amita Swadhin, stated that a Survivor Speak Out is a way of “respecting the agency of survivors” by allowing them to control their own narratives within a community of care.1 For the next two hours, survivors publicly shared their stories, read poems, and made statements of love and support to others.

A week later, I interviewed the two student interns at the Womxn’s Center who had planned the event—Anna and Taylor—to learn more about their intentions for Take Back the Night. 2 They explained that they had wanted to create a space that was intersectional and inclusive for a variety of survivor experiences. Taylor described TBTN as an “origin point” for survivors to see they are not alone and make connections with other people dealing with the same thing. They explained this shared experience in speaking out facilitates both healing and activism for future conversations.

The idea that sharing your story leads to healing, community, and activism is foundational to the framework of TBTN. Take Back the Night began in the 1970s as a form of feminist mobilization built upon the idea that collectively acknowledging the shared experiences of survivors has the capacity to render the personal political. In the context of sexual violence specifically, testimony is frequently figured as a way to restore victims’ agency and “shatter the silence” of sexual violence. Finding language can enable recognition through witnessing and validate claims to justice and belonging. Yet at the same time, the imperative of testimony demands linear coherence and graphic details of injury, which can lead survivors to experience victim-blaming, attacks on their credibility, and institutional betrayal (e.g. Baxi 2014; Matoesian 1993; Mulla 2014).

In my research and experience working as a survivor advocate, I did, in fact, witness survivors find ways to refuse these narrative demands within institutional contexts such as advocacy and Title IX investigations. Clients sometimes withheld disclosing details about what brought them to seek support from the CARE office, or they refused to answer questions they deemed irrelevant during Title IX hearings. In this essay, however, I will focus on the narrative potentials of Survivor Speak Outs as a means of demanding accountability, building community, and fostering wellbeing. Rather than sharing details of harm or fully accounting for what happened from beginning to end, survivor stories approached their experiences of harm and healing in fragmented form; they took control of their narratives on their own terms.

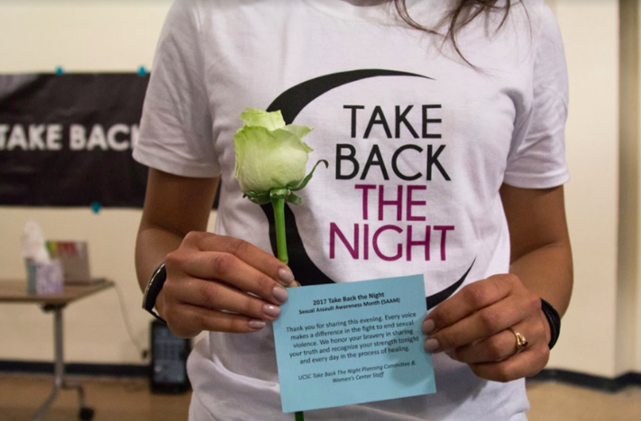

Survivors who spoke at the 2017 Take Back the Night event were given a rose and card that thanked them for “sharing your truth.” Photo credit: Danielle De Rosario, City on a Hill Press.

Rooted in resilience

Three years after the 2017 TBTN event described above, I found myself responsible for overseeing the campus’s awareness events. I was employed by the UCSC CARE office as an advocate and prevention educator while conducting my dissertation research. April’s TBTN was scheduled one month after the University of California shuttered on-campus operations and sent students home due to COVID-19. Throughout the pandemic, CARE advocates heard from student-survivors that they were struggling with severe isolation and mental health challenges. While we suddenly could not gather together in-person, I organized a virtual forum where survivors could submit their stories, art, and poetry under the theme “Rooted in Resilience.” We allowed survivors to indicate where they wanted their work published—in an e-book, an online gallery, and/or on social media. Our intention was to foster the conditions for solidarity and healing through storytelling that had long been TBTN’s aim, and in so doing, to counter the collective trauma of the pandemic.

The 10 submissions published in 2020 offer vulnerable and intimate fragments of surviving in the wake of sexual violence.[1] They range from poems to hand drawn images, to short fiction chapters, to photographs, and memoir-style narratives. While legal and institutional processes elicit graphic descriptions of victimization, poetic formations such as these call attention to this voyeuristic demand in their refusal to describe what happened. Only one narrative describes their physical injury. The rest redact the detail of naming all together, and instead talk around their experience by referencing the actions that caused them harm: “your ‘erratic behaviors’”; “his cold fingers”; “a past I never consented to”; “something taken from you over and over again.” The storytellers describe the lasting impacts on their emotional wellbeing, their relationships, their academic performance, and their sense of self-worth, but refuse to be reduced to their trauma. One survivor leans into her anger with a poem titled, “I’m Ugly”:

My reflection is an ugly woman,

Filled with anger

And vexation.

Who will strike back

Without hesitation

I read this author as writing back against the demand to portray herself as a “perfect victim.” Through all these articulations and silences, I see the authors trying to control the terms of their own representation against the scripts of trauma and recovery that are typically expected of survivors.

Fragmentation does not have to reduce the subject; survivors also insist on putting their stories in the context of their identities and the structural oppressions they face. One story, “Untitled,” discusses the month of April, which is centered annually as a time of prevention and awareness, as a painful reminder of her being “robbed” of her consent, of her stepfathers’ deportation, and of her mother’s struggle to cross borders. Mimicking the nature of trauma by highlighting cyclicality and triggers, the author entwines questions of citizenship and poverty with those of sexual violation, bridging the personal and political. Here I read fragmentation as enabling possibilities for broader claims to recognition and social justice.

This story and the others not only describe survivors’ pain, but also survivors’ joy, aspirations, and resiliency, and in so doing, complicate what we expect from survivors. The author of the poem “I’m Ugly” also submitted a second poem, “I am Hope.” Here, she focuses on her healing process and sent a message of affirmation to other survivors:

I am Resilience,

I am Courage,

I am Strength,

& I am Hope.

And on your darkest day,

Just know

You can still float!

I read the shift in subject from “I” to “you” in this poem as manifesting a community of care through witnessing and shared acknowledgment. Bound together in an e-book, the collection of stories creates belonging and manifests a world otherwise for survivors—a world beyond and without violence.

Poetic possibilities

The story fragments offered by survivors paint both a devastating and a hopeful portrait of living in the wake of sexual violence. They hold within themselves the value of telling and listening to others’ stories—of witnessing as a practice of care. By carefully listening to survivors at UCSC as a researcher, advocate, and educator, I saw that the context, form, and content of their narratives afforded different potentialities for care, healing, justice, and belonging.

I’m compelled by the fragmented form of survivor storytelling. Yet by naming “the fragment,” my intention is not to suggest that these narratives are merely part of a “whole” that is more real, more complete, or more true. Rather, I use the fragment as a heuristic to think through those narrative forms that disrupt teleological expectations of recovery and their attendant demands for explicit detail. As narratives that unfold in non-linear form, fragments mirror the embodied experience of trauma and memory. Fragments mark partiality and rupture. They resist sensationalizing violence. In their refusal to comply with testimonial imperatives, fragments call attention to that which is left unsaid—not to gesture toward a supposedly more complete account, but to tell a different kind of story about survival. I suggest that, in so doing, the narrative form of the fragment can build communities of care and open political possibilities for reimagining a world without violence.

By refusing and rewriting dominant scripts of sexual violence, trauma, and survival, these stories compel me as an educator and scholar to push for ways to expand our capacities and vocabularies as a means of supporting survivors and preventing violence—to listen to fragments as a practice of care. We can attune to the silences, articulations, and talk that happens around (rather than about) violence. We don’t need to become voyeurs to believe survivors. We can hold the “ugly” and the “hope” together. This fragmented form of witnessing implicates all of us who are concerned about social justice, inclusion, and belonging—all of us who are trying to care for one another in an uncaring world.

Notes

[1] Swadhin is a survivor, writer, and activist who speaks openly about their personal experiences of child sexual abuse as a way to heal through storytelling. They aim to center LGBTQ survivors of color in their work.

[2] Anna and Taylor are pseudonyms.

[3] The e-book CARE published can be viewed here: https://issuu.com/ucscsurvivorstories/docs/rooted_in_resilience.

References

Baxi, Pratiksha. 2014. Public Secrets of Law: Rape Trials in India. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Behar, Ruth. 1997. The Vulnerable Observer: Anthropology That Breaks Your Heart. Boston: Beacon Press.

Daniel, E. Valentine. 1996. Charred Lullabies: Chapters in an Anthropography of Violence. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press.

Das, Veena. 2006. Life and Words: Violence and the Descent into the Ordinary. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Hartman, Saidiya. 1997. Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America. New York: Oxford University Press.

Matoesian, Gregory M. 1993. Reproducing Rape: Domination through Talk in the Courtroom. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Mulla, Sameena. 2014. The Violence of Care: Rape Victims, Forensic Nurses, and Sexual Assault Intervention. New York: NYU Press.

Alison Hanson is a PhD candidate in Anthropology at the University of California, Santa Cruz. Her doctoral research illuminates how survivors’ experiences in the university context are negotiated through Title IX policy, institutional care practices, and ideological formations of sexual violence. She worked for two years as a survivor advocate and prevention educator in the UCSC CARE office.