It happened fast. The announcement came on the second Saturday of March. We had two days to shift our courses online. It was not ideal, but I was grateful for the university’s decision. King County, where I live, was the epicenter of COVID-19 cases in the United States at that point. I was concerned about my well-being, but more importantly I was worried about the possibility of exposing my students and my colleagues in Pierce County where I work.

Pacific Lutheran University had already begun updating its community in early March with a dedicated coronavirus website to deliver the latest news. There was general information about the virus, its spread in the state of Washington, and CDC guidelines on how to protect ourselves and those around us. It also reminded the community on a daily basis that there were no confirmed cases in Pierce County or at the university, until there were. The shift to online teaching happened at a time when it was still unclear how panicked we needed to be.

On the last in-person meeting of my afternoon class, several students were absent. Those who informed me were either sick themselves or caring for their loved ones. It is not uncommon to have students missing class or to see them coughing when season changes. Last fall, it happened around October-November. This spring, it was beginning to happen towards the end of February. I had also just recovered from what turned out to be a bad cold. Just as I thought we were getting over the seasonal cold and flu, and we could get back to our fullest capacities, the university informed us about the cancellation of in-person classes. The move to online teaching was set in motion.

The University of Washington had moved their classes online for the remainder of the winter quarter just days ago. Other academic institutions in Seattle had followed suit. Initially it seemed as though classes would be disrupted for only a few weeks until the situation was taken care of. Pretty soon, it was clear that universities and colleges in King County wanted the faculty to prepare for distance learning for the next quarter as well. This announcement marked the first shifts to online teaching in the United States in the wake of the pandemic. There were no publicly confirmed cases of the novel coronavirus south of the county, when the announcement was made. Things changed rapidly in just a matter of days.

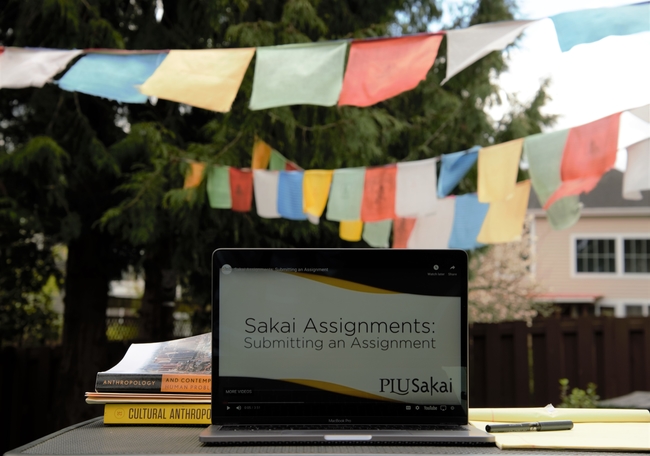

There was now a quiet rush to set up fully functioning virtual platforms for our classroom-based courses that had taken months of planning and preparing to design. I have taught online courses before and I regularly incorporate online tools in all of my courses. So, the move itself was not trying. University-offered trainings for web-based teaching have been particularly helpful in this sudden transition. At my present institution, we use Sakai. The built-in course sites on Sakai is our main platform. At other institutions, I have used Blackboard and Canvas. Some have more functions than others depending on the university you are at and the kinds of investment the university has made in them. The huge task for the teachers has been to ensure the students are able to benefit from what was designed for face-to-face learning in a distance learning arrangement.

In-class discussions and group activities had to be re-thought, access to quizzes and exams needed to be flexible, due dates for assignments had to be extended. Accordingly, grading had to be adjusted so it could fairly assess the progress of our diverse students. Some students are supported for online learning in their home environment, but others are not. So, expecting all students to perform well or attend online lectures synchronously is not practical. On the other hand, pre-recorded lectures do not afford direct interaction between students and the teacher, possible with synchronous discussions. These were the kinds of things that needed to be addressed immediately.

In the first couple of days, it was a solo effort for us in the greater Seattle area. Each faculty member I spoke to was desperately working on their courses. The upcoming spring break was a welcomed time to gradually set up our courses. As days passed, universities and colleges across the nation moved online. Eventually there were virtual meetings with colleagues and communities on social media sites to assist “pandemic pedagogy” through this unpredictable transition. Teachers began sharing resources, exchanging tips, and supporting each other.

In this precarious time, the pandemic has exposed the distress of abrupt changes to our daily routine but in doing so, it has also revealed our resilience and our ability to adapt. For many of us, direct interactions between students and teachers are irreplaceable. One of the salient reasons why many of us have resisted online teaching is the limited personal connections that is vital for holistic instruction. In the past I used to discourage the use of devices except for computers to take notes. Over the years however I have come to appreciate the use of technology in my classes since our students are entering a world increasingly dependent on it. In all of my assignments I now encourage students to “look up” topics on the Internet. I ask them to do their own independent research to complement what they are learning from the course materials. One of the objectives here is to train students to sort through excess of online sources to identify credible ones—a valuable skill for anyone in today’s world. Reflecting on these past few weeks it has become clear that the shift to online courses has forced us, whether we like it or not, to make online teaching work.In the background of course was the anxiety-causing news of the pandemic and its daily toll. Within days of the first COVID-19 death in the King county, images and videos of community members rushing to grocery stores to stock up on essentials and pictures of empty shelves circulated online. In the middle of shifting my courses, I found myself in the stores anxious to get what I thought would be necessary in case my family had to quarantine ourselves. Expectedly there were no toilet paper and cleaning supplies or flour, pasta, oatmeal, or rice. We were able to get enough of other essential items to last for a couple of weeks though.

The challenge for the teachers in this time is to stay calm and collected in the midst of a quickly spreading virus and ever-evolving directions for teaching from the university so we can be clear and consistent for the students, who are looking up to us for guidance. A week into online teaching, I was receiving emails from my students about how they were struggling to complete their coursework on time. My first online survey of the students had shown that almost all of the students had access to the Internet and a computer. However, completing coursework was not as simple and easy as that. One email described how the student was not in a position to return home even if they wanted to. This was causing them stress and anxiety. Another email described how the student was getting headaches from staring at their computer all day long for their classes. Another email described how the student had gotten ill and had a nervous breakdown from the sudden change in the course formats leaving them unable to focus. Several students who were otherwise punctual missed their assignments as they adjusted to their new life situations. This week, we are returning to class after the much-needed, work-filled spring break. It is difficult to predict how my students will perform in the second half of this semester.

What I wish my students know most right now is that they are not alone in this. Together we will get through what may seem too much to handle at the moment. I hope they know that their teachers are doing their best to provide the quality education they deserve.

Cite as: Sherpa, Pasang Yangjee. 2020. “The Online Shift.” In “Pandemic Diaries,” Gabriela Manley, Bryan M. Dougan, and Carole McGranahan, eds., American Ethnologist website, 2 APRIL 2020 [https://americanethnologist.org/features/collections/pandemic-diaries/the-online-shift]

Pasang Yangjee Sherpa is visiting assistant professor of anthropology at Pacific Lutheran University. Her research is about climate change, indigeneity, and the Sherpa diaspora. You can find her website at pasangysherpa.com