COVID-19 has engulfed the globe since March 2020, but its impact has varied across nationality, gender, religion, race, and class lines. People living in violent geographical spaces faced a double burden as their lives, threatened by both the pandemic and coercive state apparatuses. Although the United Nations called for a global ceasefire to control the pandemic in conflict zones (Mehrl and Thurer 2020), not all states and non-state actors obliged. A striking example of this was the Indian state, which saw the pandemic as a window of opportunity for breaking the will of Kashmiri Muslims, who had already experienced a military lockdown and communication blockade in 2019 when Kashmir’s special status was abrogated. Kashmir is one of the world’s most militarized zones (Duschinski and Hoffman 2011). Claimed by India and Pakistan for the last seven decades, armed resistance in Kashmir has been challenging the legitimacy of the Indian state within its territory since the 1990s. Acting as a “state of exception,” the Indian state has employed coercive methods to force the Kashmiri Muslim population into submission (Agamben 2005). Further, special laws were enacted to protect the Indian armed forces operating in Kashmir from prosecution for violations such as torture, arrest, or damage to property (Kazi 2009). During the early part of the COVID-19 lockdown, there was a remarkable surge in violent operations by the Indian military. One particular incident that drew my attention was the gutting by fire of 22 houses in the dense residential area of Nawakadal, Srinagar. This devastating event, which was heavily reported in the media, was perceived by the public as little more than a pretext by the Indian military to exercise power by using lethal explosives with the goal of “neutralizing” the rebels.

This essay is a product of my extensive ethnographic work with these 22 “survivor families” in order to gain critical insight into their experiences and amplify their narratives. Here I will focus on one particular family caught between war and the pandemic. I used a visual ethnographic approach to understand the survivors’ quotidian experiences of violence and the impact of the pandemic on their health and livelihood. This approach requires the contextualization of photographs to draw meaning from participants’ perspectives (Ball and Smith 2006). For instance, photographs of debris and half-burnt things captured by members of the surviving family not only became part of their memory, but also allowed their viewpoints and perspectives to be centred during the interviews. It was through these images that survivors were able to bring out their lived experiences. I also took photographs of the newly reconstructed spaces and conducted in-depth interviews to connect visual context with narratives of survival and resilience.

Wouste gov Mouzurr (Master turned disabled)

Sewing Machine of Farooq. Credit: K.W.Hassan.

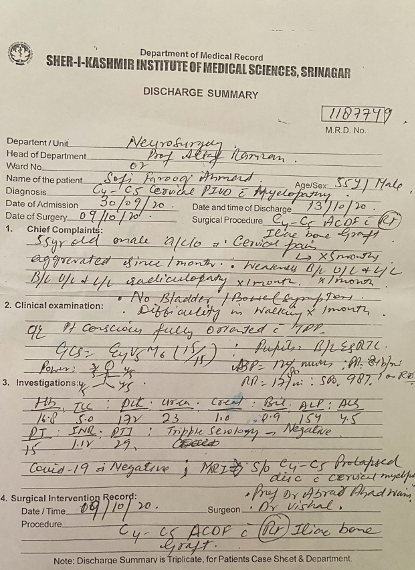

Wouste Farooq (Master Farooq), known for his profession of tailoring, lived with his wife, daughter, and son in one of the houses destroyed by the Indian military forces. He did not own a shop; instead, he would sew and mend clothes from his attic. On Sundays, he would sell used clothes in Srinagar’s weekly market. Incidentally, Wouste Farooq had renovated his house after it had been destroyed by the massive floods of 2014. On midnight on May 19, 2020, he and his family woke up by a knock at the door and a voice saying, Bahar nikloo! Come out. Indian military officers then barged into his house, and he was asked to take his family into an adjacent alley. It was a Cordon and Search Operation (CASO), and the heavy artillery caused a fire in the neighborhood. Wouste Farooq’s daughter, MF, recalled the incident: “We were scared and left in our night suits. Instead of taking precious things, such as gold and money, my father picked up his sewing machine, saying ye chum rozghar (this is my livelihood).” Along with 12 other families, they took refuge in the house of a neighbor who had a COVID-19-infected patient and a pregnant daughter at home. “At that time, we forgot about COVID, no one wore a mask, and all of us packed in the same room,” said MF. Such intimate and perilous behavior reveals how the everyday lives of Kashmiris were tested when confronted with a choice to survive between war and a pandemic. Wouste Farooq then shifted to his in-law’s house in a suburb of Srinagar called Qamarwari, where he was severely infected with COVID-19. Though he managed to reconstruct his house and rebuilt his life, the trauma caused by the violence led him to experience depression and high blood pressure, which in turn led him to experience a paralytic attack. Subsequently, he had to undergo two consecutive surgeries, after which he lost function in his right hand and his speech became impaired. This is a stark instance of how, during turbulent circumstances, people with limited choices face complex and unfolding ordeals. The violence he endured stripped him of his livelihood and reshaped his life; his body is marked by memories of loss and survival. While looking at the sewing machine in the corner of the room, MF said, “meechine bacheiye, wouste gov mouzurr” (sewing machine was saved, and the Master became disabled).

Wouste Farooq at hospital bed at SKIMS after surgery. Credit MF.

Prescription of Wouste Farooq from hospital, suggesting surgery. Credit: K.W.Hassan.

Kagzaen Loug Narr (Documents burnt down)

Debris of books and documents. Credit: MF.

Wouste Farooq’s son, SF, was studying in the ninth grade at a private school when their home was burnt down. He was emotionally traumatized by the sight of his burnt books and eventually dropped out of school. I could sense his disinterest in school from the photograph of their chaffed school bags and books, which MF showed me. MF could only recover half-burnt testimonials and transcripts. While sensitive to her brother’s situation, she demonstrated resilience by qualifying for an entrance test for a master’s program at Kashmir University. However, her admission turned out to be incomplete because she could not provide new transcripts due to the COVID-19 lockdown. In this example, we see how violence and the pandemic together produced instabilities and subverted people’s aspirations.

Looking at the photograph of the debris, Wouste Farooq’s wife, NF said, “I had kept all the important kakezaat[documents] in the same closet.” Not able to control her tears, she wept profusely, sharing that “kakhdan tei ketaban loug narr” (all of their documents and books were burnt down). These included property papers, aadhar cards (state-issued ID cards), bank passbooks, and a ration card. Not only were these documents mandatory for procuring subsidized rations and vaccinations against COVID, they would also become required documents needed by Kashmiris to prove their identity and apply for new required “domicile certificates.” Until 2019, the “state-subject certificate” was documentary proof for distinct citizenship—a provision under Article 370 of the Indian constitution (Noorani 2011). The unilateral decision of the Indian Parliament to abrogate this special status of Kashmir, however, nullified all such identity proofs. Here we see how the loss of documents can affect a people’s ability to access government resources.

Gold earrings saved from fire. Credit: K.W.Hassan.

In a conflict zone, people retrieve their memories through material possessions, conscious and externalised representations of their very being. Material possessions are active and constitutive parts of a person’s individuality and an extension of self out in the world. Many people living in conflict zones equate material loss to a parting of their identity and emotions. In the case of MF, whose wedding was disrupted due to her vardhan (dresses, bedding, and gold ornaments) being consumed in the fire, she was left with nothing except a pair of earrings. NF put them in front of me and said, “bas yehai bachoav,” only this was left. She picked it up, put her hand on MF’s head, and said, “ath manz tei shukkur, soun kumluiv insaan bachoav” (I thank God that only gold was melted; that we [humans] are unhurt). In families experiencing multi-layered grief and misery, a certain kind of subjectivity emerges which seeks comfort in unremembering material aspects of their life. NF had purchased the gold ornaments for her daughter from a local jeweller through monthly instalments. She could not make these payments because Wouste Farooq was out of work due to the two consecutive lockdowns: the military lockdown in mid-2019 followed by the COVID-19 lockdown in early 2020 (Zia 2020). Indeed, the informal sector in Kashmir was doubly hit and disadvantaged by these lockdowns.

Baiye Wathouv (We will rise again)

Kashmiri Muslims have shown individual and collective resilience against state terror. Individual members of the family rendered homeless have focused on economic pursuits by resorting to small jobs that contribute to the family income. For instance, MF has taken a part-time job at one of the vehicle showrooms in Srinagar, and her brother, SF, started working as an assistant to a local electrician. Their mother, NF, got a job as a caretaker in a nearby kindergarten. Additionally, neighbors and relatives have shared their house with the family, and the local Masjid Committee collected donations to rebuild their houses. Dar Seb, a community elder and the President of the Masjid Committee, said: “we cannot give back exactly what they have lost; nevertheless, this collective effort symbolized our unity and resilience.”

Though the stories of material loss and resilience varied across the 22 surviving families, all of them were forced to negotiate the circumstances of their everyday lives in order to have access to basic amenities and safeguard themselves from COVID. More than material, the narratives they shared with me during my ethnographic fieldwork highlight their emotional and cultural bonds to their lost “home.” The charred remnants of their homes, preserved as photographs in their cellphones as well as images in their memories, are now part of their identity. During my interactions with Wouste Farooq’s family, I often thought about words of solace I might offer, but I was fearful that each comment would sound inconsequential. To my surprise, the words of comfort came from NF: “ath manz tei shukkur jan bachouv, qamar gandav baiye wathouv.” Thank God, we are alive, she said, we will struggle and rise again.

Over the past decade, with the right-wing Hindutva regime at its centre, the Indian state has used brutal military and extra-judicial methods against Kashmiris, both at the individual and the collective level (Zia 2020). The staged encounters by the Indian military to “neutralize” the rebels, which ended up with the burning of multiple houses in the locality, was part of a collective punishment. Moreover, state surveillance has become omnipresent, choking out all spaces of dissent. Anyone raising the issue of human rights violations, or making mention of houses destroyed in encounters, is subjected to unspeakable reprisals. Until 2019, people resisted the structural violence of the militarized state through street protests, hartals, poetry, songs and graffiti on walls. Recently, however, resistance itself has transitioned from a collective, organized and explicit movement with revolutionary impact (Hollander and Einwohner 2004) to what James Scott calls a subtle or imperceptible movement, outside the obvious public domains (Scott 1990). Instead of explicitly registering their protest against this violence, destitute families made a conscious choice, which I called a “survival strategy,” to rebuild their houses in the same spots without any compensation from state institutions. This survival strategy has become a purposeful act of defiance for Kashmiris amidst apprehensions that integrationist policies of the Indian state constitute a threat to their identity and livelihood. Defending the land upon which they live and protecting themselves from the consequences of dissent are not—and will never be—acts of neutrality or compromise.

Kitchen after the reconstruction. Credit: K.W.Hassan.

Farooq at the sitting room of reconstructed house. Credit: K.W.Hassan.

References

Agamben, Giorgio. 2005. State of Exception, translated by Kavin Attell. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Ball, Michael, and Gregory Smith. 2006. “Technologies of Realism? Ethnographic Use of Photography and Film.” In Visual Research Methods, Volume IV, edited by Peter Hamilton. London: Sage, 3-58.

Duschinski, Haley and Hoffman, Bruce, 2011. “Everyday Violence, institutional denial and Struggles for justice in Kashmir.” Race and Class 52 (4): 44–70.

Jocelyn A. Hollander, and Einwohner, Rachel L. 2004. “Conceptualizing Resistance.” Sociological Forum 19(4): 533-55.

Kazi, Seema. 2009. Between Democracy and Nation: Gender and Militarization in Kashmir. New Delhi: Women Unlimited.

Mehrl, Marius and Paul W Thurner. 2020. “The Effect of COVID-19 Pandemic on Global Armed Conflict: Early Evidence.” Political Studies Review 19(2): 286-293.

Noorani, A. 2011. Article 370: A Constitutional History of Jammu Kashmir. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Scott, James C. 1990. Domination and the Arts of Resistance. New Haven: Yale University,17

Zia, Ather. 2020. “Indian Necropolitics and Weaponising COVID-19 in Kashmir.” Jindal Law and Humanitarian Review 1: 78-90.

K.W. Hassan is a researcher based in Kashmir. His research focuses on political violence, gender, and public spaces in the conflict zones of South Asia.

Cite As: Hassan, K.W. 2023. “Vulnerability and Resilience: War, Pandemic and Kashmir” In “Pandemic War-Time: Dispatches from Occupied Lands” edited by Ather Zia, American Ethnologist website, September 26 2023, [https://americanethnologist.org/news/vulnerability-an…ir-by-k-w-hassan/ ]