Nothing seems to be enough. Biodiversity is plummeting, pollution is ever on the rise, and global warming is a visceral presence. Efforts taken so far to mitigate or adapt appear to be too little, too late. And people, industries, and governments are simply carrying on as usual. How, then, do environmental activists keep going? Where do they draw their inspiration to continue working towards the profound societal shifts they seek? An easy answer would be to update Antonio Gramsci’s (or rather Romain Rolland’s) famous dictum of the “pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will.” But how is that optimism kept alive? How is it upheld, now that the climate justice movement has largely imploded, and environmentally destructive practices appear to be as engrained as ever? These are questions that occupy me. Addressing them along the crooked paths of ethnographic fieldwork has taken me, strangely, to encounters with books.

One such encounter takes place in a book store in a gentrified Berlin neighborhood. It’s a winter evening, already dark. The shop is closed for business. Yet people enter. They’ve come to attend today’s session of a reading group organized around the theme of “naturecultures.” Participants seat themselves on chairs arranged in a circle. It’s the usual mix of regular attendees and new faces, with English serving as the working language amongst this international crowd. Most appear privileged, white, and well-educated, and conservations take a heady tone.

The reading group is run by artists enthusiastic about the intersections of life sciences, philosophy, and politics. Meetings occur irregularly, and have already spanned almost seven years. Sessions are themed, and facilitators select and circulate readings, assembled from life sciences text books and research articles, philosophical treatises, works of fiction, and lab manuals.

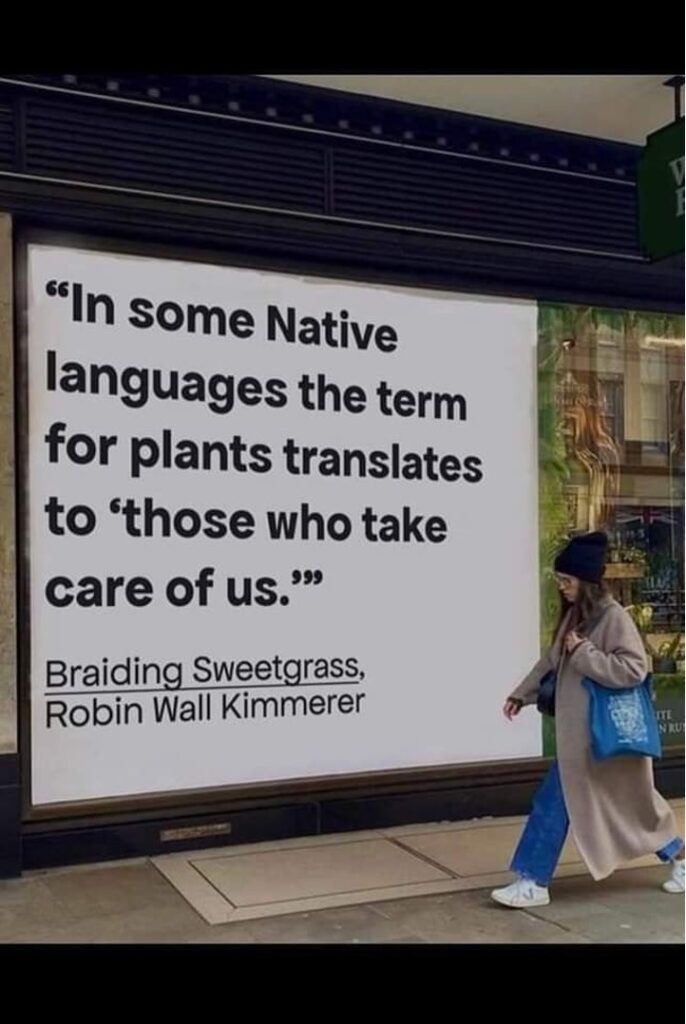

After few words of welcome, we turn to the readings. Today we read sections from one book only: Robin Wall Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teaching of Plants (Kimmerer 2020). Kimmerer teaches biology at a US university. In her writing, she attempts to bring modern science into conversation with Indigenous perspectives she has absorbed as a member of the Indigenous Potawatomi nation. In some ways, the book’s goal mirrors that of the reading circle. Both seek to bridge knowledge practices that are deemed mutually exclusive, such as “Indigenous” and “Western modern” or “science” and “art.” Braiding Sweetgrass has turned out to be quite a phenomenon. A bestseller, it is commonly referred to by my interlocutors. People praise it for its lyrical tone, and it is indeed captivating.

Screenshot from Spiritual Rewilding Facebook Page taken August 31, 2024.

As always, the reading group participants take turns reading out the selected passages, handing over to the next person whenever they wish. The passage we are reading today on this quiet winter night concerns gifts and the forms of relatedness they sustain. Kimmerer ponders other questions than those that have long occupied anthropologists. This biology professor steeped in Potawatomi thought is not so interested in how gifts interweave people into collectives. Instead, she explores how the Earth itself bestows gifts, and the forms of relatedness these gifts sustain between itself and humans.

For Kimmerer, Earth’s provisioning is a wonder. And she invites readers to return to that sense of wonder, or to stay with it. Seeing things as they really are, and acknowledging the Earth as gift-giver, she argues, helps correct ecological wrongs. At stake here is not the unearthing of specific Indigenous techniques or local environmental knowledges in order to mitigate environmental destruction; rather, hers is a call to embrace “Indigenous methods of inquiry,” to shift attention from the “level of what” to “the level of how”—how is knowledge being produced among Indigenous people (Yunkaporta 2020, 42), and how might that be useful in the current predicament? Staying with the wonder, Kimmerer argues, and honoring Earth as gift-giver, ultimately means realizing mutuality and interdependence in the web of life. What is more, it counters the tendency to treat nature as a standing reserve waiting to be exploited, as a space to dump toxic waste, or as a mere backdrop to human activities.

It would be easy to dismiss Kimmerer’s influence in this moment of profound environmental crises as naïve or overly romantic. And it certainly expresses a widespread desire for the Indigenous Other to act in the role of an exoticized dream figure. Yet, alongside such romanticizing tendencies (and the specific violence they entail), words and thoughts conveyed in books like this not only speak to the desire for an otherwise but also fuel a sense of possibility and endurance in the mode of despite. In the reading club such a sense was palpable.

In her book, Kimmerer does not make a case for an all-out return to so-called traditional forms of live. Instead, she argues for cultivating Indigenous modes of relating deep within, not in isolation from, the modern western world. For example, she asks, “but even in a market economy, can we behave ‘as if’ the living world were a gift?” (Kimmerer 2020, 31). We didn’t read that sentence on that particular winter evening, as the lights of bookshop fell on the dark sidewalk. Yet, many of the discussions and conversations I took part in while participating in the reading group seemed animated by this notion. What happens if one looks at nature with different eyes? continues to be one of the group’s guiding questions. Unsurprisingly, tonight’s proceedings take up that theme.

After an hour or so, the group has worked through the marked passages. Collective reading gives way to conversations about the text and its meaning. Following brief clarifications, participants shift to discussing the significance of this argument and how it might be implemented. As always, comments range between artistic practice, civic engagement, and environmentalism. Tonight, the conversation quickly steers towards practical applications of Indigenous knowledge in this city known for its housing crunch and rave parties.

At one point, the discussion returns to the question of the gift. In the sections that have been read aloud, Kimmerer emphasizes that humans come from the earth, and that the earth wants to sustain them. Taking something from the earth is hence not (necessarily) an act of extraction. One participant, Laura, comments that she finds it difficult to comprehend how her interactions with nature could be anything other than destructive. Can the extraction of foods actually be seen, she asks, as an exercise in mutuality? How could her doing and taking and using possibly be understood as receiving gifts? And what good would it do to sacrifice tobacco—as Kimmerer suggests—in order to return the gift? Laura struggles to transform what she sees as an instance of extraction into one of provisioning. And she struggles with what it would mean to respond to that provisioning entity.

Responding to Laura’s questions, Lisa, another participant, skirts ontological speculations. She suggests that such acts of reciprocity and practical kindness could be implemented beautifully in one’s own garden, right in the middle of the city. In that, she’s hands-on, or should I say: down to earth. And she appears committed to a playful “what-if,” practicing forms of relations as if they were real and seeking to implement the logic of gift-giving on a patch of land in the middle of this city that never sleeps.

Collective thinking about how a gift-giving Earth might be encountered within the limits of this city is an exercise, I suggest, in practicing a subjunctive, “what-if” attitude. At play here is a combination of strategic choices and a commitment to playfulness and possibilities. This combination, it seems, helps to revive hope, to fuel the ability to live in the mode of despite. But how does this work?

Pondering how food stuffs might be considered gifts of the Earth, and asking what humans might reciprocate, are driven, I suggest, by “strategic inadequacy” (Johnston 2021, cited in von Stuckrad 2024). That is, such questions assume that modern science might not always have the prime access to truth, and that other knowledge practices and rationalities should be taken seriously when it comes to solving wicked problems. Acknowledging such inadequacy creates room for alliances to emerge; but it also entails risks. After all, today “everybody wants to rethink animacy, but almost no one wants to be an animist,” at least no one among “intellectuals with degrees and reputations to protect” (Weston 2017, 26).

Besides being a strategic choice, the “what-if” also invites playfulness. It articulates dream-like explorations of what is or might be possible—not deferring them into the future, but anchoring them in the interstices of the everyday, here and now. This is what the reading group is trying to achieve, and it is what attracts participants (besides, say, indulging in the quirky pleasures of meeting in a bookstore after dark). It was, one of the facilitators told me, about seeing what emerges. It wasn’t about providing ready-made answers or roadmaps; rather, let words take over, as they are read out loud by this group of enthusiasts, and allow those sounds and ideas to make new connections and open up spaces of potentiality. Again, and again, one session at a time.

Collectively contemplating possibilities and debating how to act them out, with a “what-if” attitude, is an exercise in perplexing and unsettling. Moreover, it seems to offer a sense of agency and possibility in a world that appears ready to “slog on, mindlessly” (Hickel 2020, 289) along its pathway of exploitative naturecultures.

As a strategy, one that is driven by both inadequacy and playfulness, the “what-if”’ does something; it is a consequential act. Whether or not this strategy actually does establish a relationship of gift-exchange between a group of ecologically minded Berliners and the Earth is not important. What matters is the sense of possibility it animates in a world in which nothing seems to move, in which everything seems to be too little, too late. At the very least, it opens up spaces to imagine an otherwise, and to act on that possibility, despite the odds.

References

Hickel, Jason. 2020. Less Is More: How Degrowth Will Save the World. London: William Heinemann.

Kimmerer, Robin Wall. 2020. Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants. London: Penguin.

Stuckrad, Kocku von. 2024. “Languages of Life and the Blending of Worlds: Radical Entanglement.” Journal for the Study of Religion, Nature & Culture 18 (1): 113–129.

Weston, Kath. 2017. Animate Planet: Making Visceral Sense of Living in a High-Tech Ecologically Damaged World. Durham: Duke University Press.

Yunkaporta, Tyson. 2020. Sand Talk: How Indigenous Thinking Can Save the World. Illustrated edition. San Francisco, California: HarperOne.

Arne Harms is a Senior Researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology, Halle, Germany. Trained as an environmental anthropologist, he currently researches ethics and everyday environmental activism as well coastal displacement between Europe and South Asia.

Cite as: Harms, Arne. 2024. “Salvaging a Sense of Possibility Despite Ecological Gloom”. In “Living in a Mode of Despite”, edited by Rishabh Raghavan, Mascha Schulz, and Julia Vorhölter, American Ethnologist website, 3 October 2024. [https://americanethnologist.org/online-content/collections/living-in-a-mode-of-despite/salvaging-a-sense-of-possibility-despite-ecological-gloomby-arne-harms/]