How do people live in a world that is characterized by crisis, uncertainty, and a profound sense of not-knowing? How do people act, socially and politically, amidst conditions not of their choosing? Why and how do people engage in projects that seek to transform the world, despite expectations of failure? And what can we learn about such forms of politics by studying peoples’ everyday practices of being—and persisting—in lifeworlds characterized by constraints?

Despite the rain. Not only do people encounter seemingly similar constraints in very different ways, based on social position, personality, context or skills, often the constraint itself manifests differently—like the differently colored droplets of rain in the image—appearing as ontologically separate in the same moment. Credits: CMYK by Skurktur.

Inspired by these questions, we propose “living in a mode of despite” as a concept that takes people’s projects, aspirations, and ways of sense-making seriously, thereby broadening our insights into what it means to act politically and whose experiences count as “political.” The authors in this collection analyze both curiously optimistic and less hopeful, pessimistic ways of acting despite the existing odds, and consider practices that may seem, at first glance, pointless, disoriented, absurd, stubborn or even self-violating. Rather than attributing false consciousness, helplessness or passivity to such actions, we ask what “acting despite” may teach us about the dynamics of politics and resistance, and how such actions inform life lived in a constraint-ridden world.

Some of us note in our essays that our interlocutors’ actions emerge from and interact with a range of affective registers and feelings, ranging from anger and contempt to fear and anxiety. These feelings or “moods of despite” inform the ways by which people live and act in modes of despite. Thus, while the essays in the collection primarily employ the term “despite” as a preposition, i.e. to act without being affected by constraints, some of us also engage with the term as a noun to reveal the feelings of disdain and contempt that apprise our interlocutors’ actions.

Navigating Existential Uncertainty

Our thinking about modes of acting in despite draws from and expands prior conceptualizations of ambivalent political forms such as willful blindness (Bovensiepen and Pelkmans 2020), the art of unnoticing (Lou 2022), failing forward (Rao 2022), unanticipated uses of conventional formula and cynical detachment (Yurchak 2005), and enjoyment and laughter (Franck 2022). Furthermore, acting despite allows for a re-thinking of more established anthropological categories—for instance “lived experience”, “the political,” and “ethical action”—by considering events and actions that lie at the limits of conscious experience (Heyes 2020) and moral vindication (Borneman 2015). Along these lines, we explore passive, subjunctive, and strange forms of being political that emerge in a world on fire.

The concept of living in a mode of despite thus contributes to a debate that is arguably symptomatic of our time: it becomes a relevant concept and gains currency at a time that has been characterized by an urgent sense of multiple crises. Several of them are global in nature, such as wars, climate change, pandemics, austerity, or concerns about rising populism and conspiracy theories. Nevertheless, how these crises shape people’s lives, if at all, varies considerably. Needless to say, crises are hardly new but have been experienced by many people, especially the marginalized and underprivileged, for a long time. Even “shared” crises, like environmental pollution or climate change, result in different problems and experiences for different people across the world. The polysemic nature of contemporary crises and their effects are well-captured in the different essays of this collection. For instance, while Arne Harms’s contribution highlights how Berlin’s white climate activists mobilize “indigenous ways” to generate hope and inspiration at a time of inadequate political actions, the South Indian fishermen in Rishabh Raghavan’s essay are concerned with petrochemical pollution not only because of its general harm to the environment but also because it threatens their identities as fishermen. In other words, while the lives of Berlin’s middle-class climate activists and the fishermen from South India might be tied together by a global crisis, their immediate concerns are shaped by constraints that are situated and particular. Our concept sits with this rupture of scales and temporalities, speaking to situations of existential uncertainty, powerlessness, and abandonment in which social actors confront and grapple with perceived (im)possibilities, actively throwing themselves against the world or adopting strategies that appear more passive. Reading the essays together, it becomes clear that there is no singular mode of despite; rather, it can take many forms, resulting in various attitudes and affects.

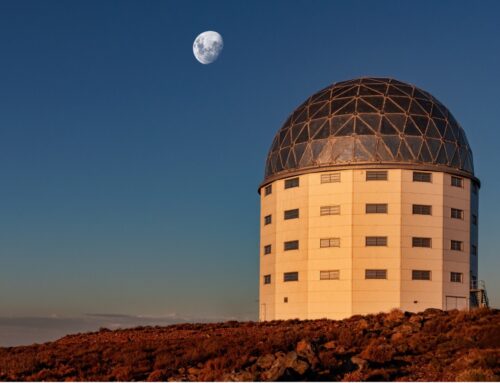

Living or acting in a mode of despite entails a curious mix of activity and passivity, highlighting both agency and structural constraints. This becomes especially apparent in the everyday struggles of Bibek in Stefanie Mauksch’s essay. Condensed in his saying “ke garne” (what to do?) are both Bibek’s resignation and disillusionment with the prospects of social change for visually impaired persons in Nepal as well as his ongoing commitment to keep struggling to be seen differently and recognized as more than just being blind. Living in a mode of despite suggests that there are powerful forces working against one’s desires and projects; ignoring or resisting them may result in punishment, harm or ridicule but, paradoxically, for this very reason, may also be a source of pride and self-esteem. Our essays show that people’s actions often transcend simplistic understandings of resistance or complicity. While most of our interlocutors are aware of the constraints that limit them, they try to “navigate” (Vigh 2009) through, around, and within them in ways that appear both intentional and arbitrary, and therefore divergent, but not necessarily contradictory. This idea is well captured in Mascha Schulz’s essay on political imprisonment in Bangladesh (which politicians experience as both normal and extremely disrupting and problematic) and Hanna Nieber’s description of South Africa’s “audacious” bid to become the first African nation to host a global astronomy summit (which both affirms the struggles faced by science in Africa and boldly ignores them). Accordingly, the two authors propose a “both/and” framework as opposed to an “either/or” understanding of what it means to act despite the odds. They suggest that living in a mode of despite is a concept that can reveal and highlight the multiple—at times hopeful, at times pragmatic, and at times unintended—enactments of people’s agency amidst limits and constraints. The both/and is also addressed in Lukas Ley’s essay on the water hyacinth, an invasive free-floating freshwater plant that both rinses and hampers the flow of the Banger River in Indonesia, and has disastrous consequences when its growth gets out of control. Ley describes the efforts by residents of a coastal neighborhood to live with and despite the plant, and their attempts to “gnaw” at local government authorities so that the latter will intervene in managing the plant’s outbreak.

Modes and Moods of Despite

Living or acting in a mode of despite is a form of political action but also a way of experiencing the world. Thus, this collection is also interested in people’s ways of meaning and sense-making regarding the conditions they neither agree with nor feel they can change. How do differently positioned people across the globe experience, and live through, forms of existential uncertainty? How do they shift—continuously, without ever settling on one of the two—between hope and desperation? And how do moods of despite mobilize people into action?

Modes of despite reflect particular affective orientations to the world that often result from ambiguous attachments: wanting and not wanting something at the same time, desiring to be a part of something while also desiring to break free, feeling that one’s actions recurrently perpetuate that which one knows is harmful, a sense of complicity. Living in a mode of despite often entails being in a permanent state of latent contradiction, longing, or “cruel optimism” (Berland 2011)—being stuck in a situation of tension that cannot be fully resolved. Often, but not always, living in a mode of despite entails a sense of futility, an eternal mode of “hanging in there” without ever feeling that anything is really changing. This kind of sentiment is well captured in Julia Vorhölter’s essay on the “stubborn hope” of (some) insomniacs who lie in bed and wait for sleep despite knowing that it probably will not come. Stubbornly hoping—for sleep or other things that seem desirable but (just) out of reach—then speaks to people’s ability to “persist in worlds and bodies that [they] find hard to accept and almost, but not quite, impossible to change.” Vorhölter’s essay highlights that while some people are chronically stuck in a mode of despite, it is also a dimension of all living.

Moods of despite, whether positive or negative, often enable political actions “against the odds.” Bani Gill’s essay, for instance, highlights how “speculative optimism” drives Karen—a Nigerian refugee in Delhi (India)—to persist in her struggle to obtain an Indian government issued biometric ID card (aadhaar) despite the bureaucratic challenges she faces due to her refugee status. Thereby, Gill argues, speculative optimism is not simply an individual attitude but one that results from and is upheld by the unpredictability and arbitrariness with which the Indian state handles demands by refugees and asylum seekers. As a mood of despite, speculative optimism is characterized by a range of (contradictory) affects and emotions, including frustration, anger, perseverance, and hope. Other essays in this collection show that various attitudes of despite are condensed by their interlocutors in significant phrases such as “what if” (Harms), the strategic use of the term “audacious” (Nieber), or phrases such as “ke karne” (Mauksch). These emic expressions signify hope, futility, and bravery in situations where people act and take risks while expecting failure. Thus, they emblematically capture “moods of despite” and how they are revealed in different social settings.

Politics of Despite

By ethnographically exploring the diverse moods and modes of what it means to live and act despite restrictive and limiting situations, we enter into conversation with a large body of anthropological literature on resistance (Scott 1985), refusal (McGranahan 2016; Simpson 2016), fugitivity (Campt 2014), resilience (Eitel 2023), and on paradoxical forms of agency such as waiting (Auyero 2012), stuckedness (Hage 2009), yearning (Jansen 2015), and patiency (Mazzarella 2021). Yet, we suggest that living in a mode of despite is different from resisting, refusing or being resilient. While the concept suggests some form of antagonism or confrontation, there is often no clear enemy; in many situations actions in a mode of despite are neither for or against the system, but simply “against the odds.” Living in a mode of despite is about persisting more than resisting; it can be a form of disagreement, but one that is not always explicit and perhaps less conscious than acts of refusal. In some cases, calling on people to act despite can become a resource and a form of mobilization; acting despite can be strategic and creative, individual or collective.

Living in a mode of despite, as we understand the concept, then, means holding out amidst hardship while longing for improvement or trying to maintain a sense of agency while faced with unbearable, often inescapable and seemingly unchangeable, conditions. Yet, several essays also show that the “unbearable” often becomes normalized as the life that people have to live. Schulz’s essay on political imprisonment based on false accusations shows that people can be simultaneously highly critical of the power structures that work against them while also downplaying and rejecting their influence. Schulz emphasizes that her research interlocutors continue their politics not just despite but also because of the odds they face.

Lastly, the concept of living in a mode of despite captures not just our interlocutors’ but perhaps also our own attempts as academics to resist and struggle in and against a—neoliberal, capitalist, exploitative—system in which we are caught, and which we often end up affirming and reproducing through our actions. Most of us nevertheless believe that—despite academic precarity and despite anthropology’s often very marginal public voice—there is still value in pursuing critical research, and that listening to, learning from, and documenting our interlocutors’ lifeworlds, struggles, ambitions, and ideas may contribute, if minimally, to a change of perspective (even if it’s just our own). In this sense, the essays in this collection have been written “in a mode of despite.”

References

Auyero, Javier. 2012. Patients of the State: The Politics of Waiting in Argentina. Durham; London: Duke University Press.

Berlant, Lauren. 2011. Cruel Optimism. Durham: Duke University Press.

Borneman, John. 2015. Cruel Attachments: The Ritual Rehab of Child Molesters in Germany. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Bovensiepen, Judith, and Mathijs Pelkmans. 2020. “Dynamics of Wilful Blindness: An Introduction.” Critique of Anthropology 40 (4): 387–402.

Campt, Tina. 2014. “Black Feminist Futures and the Practice of Fugitivity.” Helen Pond McIntyre ’48 Lecture, Barnard College, October 7.

Eitel, Kathrin. 2023. “Resilience.” In The Open Encyclopedia of Anthropology. Online: http://doi.org/10.29164/23resilience.

Franck, Anja. 2022. “Laughable Borders: Making the Case for the Humorous in Migration Studies.” Migration Politics 1 (4): 1–16.

Hage, Ghassan. 2009. “Waiting Out the Crisis: On Stuckedness and Governmentality.” In Waiting, edited by Ghassan Hage, 97-107. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press.

Heyes, Cressida J. 2020. Anaesthetics of Existence: Essays on Experience at the Edge. Durham: Duke University Press.

Jansen, Stef. 2015. Yearnings in the Meantime: “Normal Lives” and the State in a Sarajevo Apartment Complex. New York; Oxford: Berghahn.

Lou, Loretta Ieng Tak. 2022. “The Art of Unnoticing: Risk Perception and Contrived Ignorance in China.” American Ethnologist 49: 580–594.

Mazzarella, William. 2021. On Patiency, or, Don’t Just Do Something, Stand There. Academia.edu

McGranahan, Caroline. 2016. “Theorizing Refusal: An Introduction.” Cultural Anthropology, 31 (3): 319–325.

Rao, Ursula. 2022. “Policy as Experimentation: Failing ‘Forward’ Towards Universal Health Coverage in India.” Social Anthropology/Anthropologie sociale 30 (2): 81–100.

Scott, James. 1985. Weapons of the Weak: Everyday Forms of Resistance. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Simpson, Audra. 2016. “Consent’s Revenge.” Cultural Anthropology 31 (3): 326–333.

Vigh, Henrik. 2009. “Motion Squared: A Second Look at the Concept of Social Navigation.” Anthropological Theory 9 (4): 419–438.

Yurchak, Alexei. 2005. Everything Was Forever, Until It Was No More. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Rishabh Raghavan is a Research Fellow at the Max Plank Institute for Social Anthropology in Halle, Germany. His research interests include toxicity, environmental pollution, infrastructures and labor in India. He is currently working on his first book manuscript as well as developing a second project about climate change and industrial disaster in India’s southeastern coastline

Mascha Schulz is a Research Fellow at the Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology in Halle, Germany, whose research focuses on politics, (non)religion, and law in Bangladesh. Her recent publications include the edited volume “Global Sceptical Publics: From Non-religious Print Media to ‘Digital Atheism’” (UCL Press, 2022, co-edited with Jacob Copeman) and the special section “The Anthropology of Nonreligion” in Religion & Society (2023, co-edited with Stefan Binder).

Julia Vorhölter is a Senior Research Fellow at the Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology in Halle, Germany. She has conducted extensive fieldwork in Uganda on a wide range of topics, including perceptions of socio-cultural change, post-war humanitarian interventions, gender and generational relations, and emerging forms of psychotherapy. Her current research is based in Germany and focuses on experiences, assessments, and treatments of (disordered) sleep.

Cite as: Raghavan, Rishabh, Mascha Schulz, and Julia Vorhölter. 2024. “Living in a Mode of Despite”. In “Living in a Mode of Despite”, edited by Rishabh Raghavan, Mascha Schulz, and Julia Vorhölter, American Ethnologist website, 3 October 2024. [https://americanethnologist.org/online-content/collections/living-in-a-mode-of-despite/living-in-a-mode-of-despiteby-rishabh-raghavan-mascha-schulz-and-julia-vorholter/]