Hasnapur’s post office is a modest complex which also houses an Aadhaar (national identification number) registration center. Although the latter opens at 9 AM, applicants are advised to begin queuing by 7 AM to obtain the necessary forms. As I sit with Karen in her one-room apartment where she lives with her two young children, she explains that she has experience of waiting in this line for nearly two hours, only to be rudely turned away once she finally reached the counter. I ask why, and she explains:

“They said I have a Nigerian passport, not an Indian one so I can’t get Aadhaar. But I think he was not aware of the system. The problem is that this is a very local neighborhood; people are not used to seeing foreigners, and their English is not good. So, I think I should go to another place… I know that if you live in India, you can get Aadhaar. They just don’t want to give it to me…”

Karen, a Yoruba Nigerian woman in her late thirties, came to India as a student in 2016 and is currently registered as an asylum seeker in Delhi. A single mother, Karen fears returning to Lagos, which she describes as plagued with violence, crime, and insecurity. Yet her everyday life in Delhi is also fraught with challenges. A graduate in tourism management, Karen dreams of securing stable employment and relocating to a “better” neighborhood than Hasnapur, one of Delhi’s numerous densely populated “unplanned” settlements (Mukhopadhyay et al. 2015). Yet, such desires also beget documentary dilemmas; for instance, salaried employment requires for her to have an Indian bank account, but the latter requires an Aadhaar card, ostensibly contingent upon her residence status. Karen asserts that she knows plenty of Africans in Delhi who have Aadhaar. Her inability to obtain one, she claims, is due to the officials’ ignorance of “the system” that makes them not “want” to give her Aadhaar.

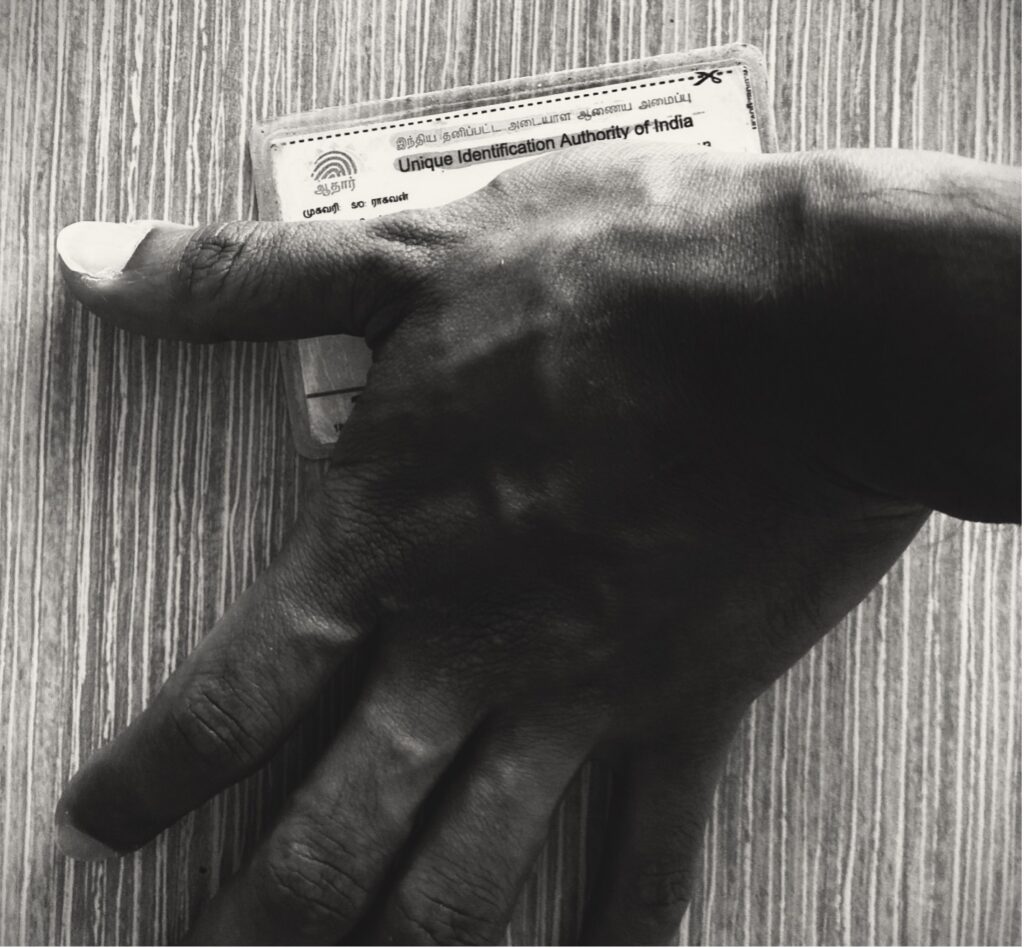

Aadhaar ID Card. Photo by Rishabh Raghavan, permission obtained by author.

Aadhaar is India’s 12-digit individual identification number intended to serve as proof of identity. Theoretically, Aadhaar is not tied to citizenship and is accessible to any resident of India. Its primary aim is to streamline access to services (e.g. banking) and welfare provisions. Recent years have witnessed a change in mandate, whereby the Government of India has excluded certain non-citizen groups, such as Rohingya refugees, from accessing Aadhaar (Tiwary and Field 2021). Even so, considerable ambiguity remains regarding who is eligible for Aadhaar and which documents are required to obtain it. My fieldwork, too, has documented instances of African residents possessing Aadhaar cards. In this context, Karen’s allegation that “they” don’t “want” to give her Aadhaar is plausible, highlighting how bureaucratic artifacts are subject to layers and hierarchies of interpretation, translation, and circulation (Horton and Heyman 2020).

For Karen, the illegibility of state practice (Das and Poole 2004) concerning documentation produces uncertainty in the everyday, obfuscates sense-making about potential futures, and impedes the planning of desired outcomes. Yet, this very indeterminacy of state functioning also opens avenues for, what I term, is a “speculative optimism” that pulsates at the interstices of not-knowability, which thrives in the gaps between the attritive efficiency of protocol and the hope-laden unpredictability of circumstance. The productive capacity of speculative optimism here constitutes the substance of “living in the mode of despite” (Raghavan, Schulz, and Vorhölter, this collection) through the imagining, crafting, and doing of continual forms of action notwithstanding the odds. The speculative optimism underlying such gambles of thought and action can encompass modes of affect, emotion, religiosity, belief, as also performance and politics. Anthropological perspectives have demonstrated how negotiations with local government institutions and agents draw upon repertoires of cultural competence; feelings of alienation as those of deservingness are powerful tropes through which the state is conjured into being (Gupta 1995; Routray 2022). Karen, too, expresses confidence in “the system” with speculative optimism routed in and through governmental machinery. For her, “the system”—implying an impersonal set of governmental norms, rules, and institutions—appears clear, just, and effective, while it is a localized “they”—typically lower-ranking, non-English-speaking, public-facing officials—who are positioned as problematic, not least because their provincialism makes them discount foreign bodies and documents. Informed by colonial and classed logics of hierarchy, Karen’s specific positioning—as a racialized black woman, as a migrant claiming refugee status in India, as a single mother seeking support for her children—shapes her commentary about the different regimes of power that state officials are invariably embedded in. Positing a divide between an impersonal “system” and a personalized “them” allows her to maintain a cultural understanding of the state as “neutral,” thus sustaining the speculative optimism that underpins her efforts to resolve her Aadhaar documentary dilemmas.

Karen recounts several other stories of “them” working against her, for instance the time she tried to open a bank account in Hasnapur:

First, they asked for my passport and visa. I gave my passport and blue card. Then they said I should bring my rental agreement. I took that. Then the man said I should bring my police verification. I submitted that. Then he said to get a letter from my landlord … he was just listing things and I could tell that he’s not interested in helping me… Even when I got everything, he said I need Aadhaar…

I attempt to explain that the UNHCR-issued asylum-seeking document—which Karen refers to as a “blue card”—may not be recognized as a visa, but Karen is not convinced. That she was able to procure the “blue card” after sustained effort and repeated visits to the UNHCR and its auxiliary offices sustains her hope that “the system” will eventually reward her with a favorable outcome; all that is required is more work and effort on her part. Alongside her strong belief in “the system,” speculative optimism encompasses material practices. It demands intensive labor to collect relevant information, familiarize oneself with complicated processes of asylum seeking, and fill in forms and documentation, and it requires the power of appeal, storytelling, and persuasion. At the same time, speculative hope is distributed across diverse spaces and entails multi-pronged strategies, even as Aadhaar remains at the forefront of Karen’s goals and desires.

Speculative Optimism Despite the State

In January 2022, Karen recruits me to accompany her to the Aadhar center so I can assist with translation. Hasnapur’s red-and-yellow post office stands adorned with various signboards and advisories; the Aadhaar counter is located in the rear. Karen, her children, and I arrive at the premises around noon, and the security guard informs us that it is lunchtime. Given the considerable queue of people milling about, it is clear that we will have to wait our turn.

Amongst the several documents required for an Aadhaar application, Karen needs a rental agreement. Her property broker, Raj, was supposed to provide it months ago when she first moved into her current apartment but has been slow to respond. He is supposed to deliver it to the center today, and a heated argument ensues between him and Karen when he finally arrives. Karen accuses him of delaying the document, while he places the blame squarely on her landlord. The young, male property broker alleges that the landlord doesn’t want Karen using his address for her Aadhaar and is threatening to evict her. Raj disparages the landlord, calling him difficult and prejudiced, but says he will manage him as long as she pays the rent on time. Promising to keep an eye out for another apartment, he takes his leave.

Around 1:30 PM, Aadhaar activities resume. Once we finally reach the counter, I take the lead in explaining Karen’s situation in Hindi, and we submit her passport, rental agreement, and “blue card.” The official asks for a visa, and I explain how the “blue card” grants her the right to stay while her asylum claim is being processed. Looking into his computer—presumably at a checklist—he informs us that these documents are insufficient; Karen requires a valid bank account as well as a letter from the local Member of Legislative Assembly (MLA) certifying her residency in Hasnapur. Only once she can supply these supporting documents would her application be considered.

I translate this information to Karen as we head out and ponder this catch-22 situation: Karen can’t open a bank account without Aadhaar, but she requires a bank account for Aadhaar, and more documents to boot. We reach Karen’s home and call the NGO that is assisting Karen with her asylum case to seek further clarity. They inform us that the “blue card” is neither a visa nor proof of residency and that only refugees are eligible for Aadhaar. This information contradicts what we learnt at the Aadhaar center, where Karen—despite her asylum-seeker status—wasn’t turned away but rather asked to produce more paperwork. Worried that the NGO may unfavorably assess her efforts to gain Aadhaar, Karen abruptly terminates the conversation.

The long, eventful day has presented Karen with several dilemmas. Should she try to get a letter from the MLA? Should she find another apartment since her landlord doesn’t want her using his address? But this involves significant time and money. Instead, maybe she could try opening a bank account to expedite her Aadhaar case. But here, too, her eligibility to open one is unclear. The larger questions also remain: Will the Aadhaar aid her residency claim in India and help her children? Or should she focus on her UNHCR refugee application? Given the conversation with the NGO, could it be that the refugee application runs the risk of jeopardizing her quest for Aadhaar, or vice versa?

Karen faces complex decisions, embedded within a dynamic socio-political landscape, with no guarantee of success. Yet, this mode of existence does not deter Karen, who is driven by the sheer possibility that circumstances may change. Speculative optimism is woven into her gambles of choice, supported not least through her criticism of local officials and her effective identification of the ambiguities embedded in “the system’s” everyday functioning, ambiguities that engender potential opportunities for success. In her repeated visits and appeals to the UNHCR, the Aadhaar center, and the banks, she performs the same actions with variations— recruiting translators such as myself or arming herself with more documentation—with the expectation of different outcomes. She demonstrates the capacity to experiment despite the supposed rigidity of standardized procedures.

Such capacities to creatively maneuver around obstacles generate conceptual openings to rethink how speculative optimism facilitates survival and existence. Living in the mode of despite resembles notions of resilience, refusal, and agency. Yet such modes of speculative optimism are more opaque, more ambiguous in their politics—a combination of naïve opportunism and strategic ignorance or, at other times, drawing upon belief in the neoliberal rationality of hard work combined with the religiosity of prayer. As I take my leave that day, Karen shares her plans to go to the MLA. She finishes with the words: “I know soon everything will be fine. I just have to pray, and the lord will be with me.”

References

Das, Veena and Poole, Deborah. 2004. “State and Its Margins. Comparative Ethnographies.” In Anthropology in the Margins of the State, edited by Veena Das and Deborah Poole, 3–33. Santa Fe: School of American Research Press.

Gupta, Akhil. 1995. “Blurred Boundaries: The Discourse of Corruption, the Culture of Politics, and the Imagined State.” American Ethnologist 22 (2): 375–402.

Horton, Sarah B. and Heyman, Josiah. 2020. Paper Trails: Migrants, Documents, and Legal Insecurity. Durham: Duke University Press.

Mukhopadhyay, Partha, Subhadra Banda, Sheikh Shahana, and Patrik Heller. 2015. “Categorisation of Settlement in Delhi.” Center for Policy Research, Delhi.

Routray, Sanjeev. 2022. The Right to be Counted: The Urban Poor and the Politics of Resettlement in Delhi. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Tiwari, Anubhav Dutt and Field, Jessica. 2021. “The Real Effect of India’s Digital Discrimination of Rohingya Refugees.” Article 14.

Bani Gill is a Marie Skłodowska-Curie Research Fellow at the Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology, Halle, and a Junior Professor at the Institute for Sociology, University of Tübingen. Her work explores migration, urbanism, identity, bureaucracy and the state.

Cite as: Gill, Bani. 2024. “Documentary Dilemmas in Migrant Delhi”. In “Living in a Mode of Despite”, edited by Rishabh Raghavan, Mascha Schulz, and Julia Vorhölter, American Ethnologist website, 3 October 2024. [https://americanethnologist.org/online-content/collections/living-in-a-mode-of-despite/documentary-dilemmas-in-migrant-delhiby-bani-gill/]